About three years ago, I realized I needed to reorganize the first few weeks of my early US history survey course. Following the 13 colonies-centered chronology of the textbook made the course seem too familiar to students and encouraged rote memorization. Still, I worried that too many changes would make the course difficult for freshmen and sophomores to navigate. The Bridging Cultures program gave me the confidence to embrace the challenge of teaching transnationally and offer students alternatives to the standard history texts and narratives.

So far, my revisions to the US history survey have focused on explaining the economic and social incentives that motivated British interests in the Americas. I capitalized on students’ initial curiosity about Roanoke, Jamestown, and New England by encouraging them to learn more about some of the laborers in these communities. For example, I assigned Sally Cabot Gunning’s novel Bound, which is based on a real 1760s legal case against a pregnant indentured servant in Massachusetts. We used the fictional servant’s example to analyze forced labor, women’s rights, and other themes across extended time periods. I found that many students read ahead of the assigned sections and shared their opinions about her choices in the classroom. Several even asked questions that the author responded to by e-mail. It was one of the most engaging semesters I have ever experienced, but I would not have changed my lessons this way without the guidance of the Bridging Cultures program.

Because I used to teach online courses each semester, I also combined some lessons about British Americans, labor, and the Atlantic world into an original e-learning site: “Voices of Labor in the Atlantic World.” The eight-page website presents primary sources from former slaves and indentured servants while offering a variety of resources to help students analyze the workers’ experiences. Students browse maps created before 1850, trace one worker’s route across the Atlantic, and write a short explanation of how features like ocean currents and disease trends may have influenced that person’s travels. Other written or multiple choice questions provide automatic feedback when students review the details of material culture examples, documents, images, and statistics.

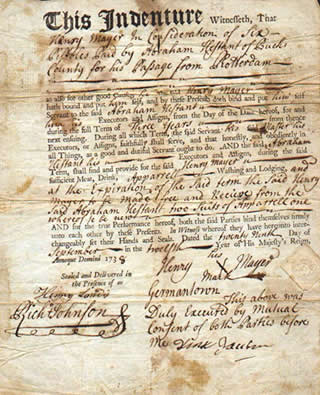

The website also incrementally introduces students to the global perspectives I gained from the Bridging Cultures program. The first page discusses the familiar story of Virginia Company explorers and provides a list of relevant key terms from an introductory textbook. The following pages broaden the Virginia Company narrative through the inclusion of resources from West Africa, Britain, the Caribbean, and British Canada. I found that when students chose among four firsthand accounts from forced laborers in the early Americas, they became emotionally invested in these readings. Half of the students chose to challenge themselves by reading letters from a teenage indentured servant or a Jamaican slave rebellion leader, even though the excerpt from Olaudah Equiano was more recognizable. They braved the antiquated spelling in a 17th-century indenture contract to analyze the impact of such business arrangements on landowners, servants, and colonial officials. And every student submitted the final task: a thesis statement suggesting how trans-Atlantic travel shaped the experiences of two forced laborers between 1600 and 1800. Since it is difficult to encourage online students to complete written responses, the high rate of participation so far suggests that this website will help motivate future students to practice their historical synthesis skills.

Starting next spring, I plan to assign my website and Bound to thematically reorient the first six weeks of my US history survey. Rather than begin chronologically, the lessons will combine specific events from ancient history through the 18th century to help students recognize the work habits, foods, housing needs, and community structures that all people living in North America relied on to survive. The textbook reading will supplement in-class lectures organized by significant trends like epidemics and mercantilism.

In hope that the website may produce similar results for other college faculty, I have made it available at the following address: https://www.utdallas.edu/~kdh140430. The resource links will be updated through next year, and I will be happy to hear your feedback if you choose to adapt it as a class assignment. My current syllabi for the two courses that include Bridging Cultures content are also available below for future reference.

In the Bridging Cultures Resources

- Course Description and Syllabus for United States History I: US History to the Civil War

- Course Description and Syllabus for Themes in the Social History of the United States: Migration and American Civilization, 1830s to 1960s

Check out the complete resources

is an assistant professor of African American history at the University of Texas at Dallas. She taught at Del Mar College from 2009 to 2014. Her specialties include Protestant missions in the United States, race relations, civil rights movements, and oral history.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.