Most undergraduates I teach know that Americans have celebrated World War II more than they have the war in Vietnam. They are familiar with the fact that the former has often been referred to as a “good war” and that the latter was a source of bitter controversy. Thus, they readily understand the variation they often see in the way Hollywood treated these wars in feature films. Most World War II movies they watch are largely supportive of the war effort. The Vietnam films tend to be more critical of the American struggle in Southeast Asia. Many of the students have also read the personal stories by Vietnam veterans such as Philip Caputo that accuse World War II movies of making combat seem glorious and convincing many young men in the 1950s and 1960s to fight. Caputo recalled that as a young man he dreamed of “charging up some beachhead like John Wayne … then coming home a suntanned warrior with medals on my chest.”1

Most undergraduates I teach know that Americans have celebrated World War II more than they have the war in Vietnam. They are familiar with the fact that the former has often been referred to as a “good war” and that the latter was a source of bitter controversy. Thus, they readily understand the variation they often see in the way Hollywood treated these wars in feature films. Most World War II movies they watch are largely supportive of the war effort. The Vietnam films tend to be more critical of the American struggle in Southeast Asia. Many of the students have also read the personal stories by Vietnam veterans such as Philip Caputo that accuse World War II movies of making combat seem glorious and convincing many young men in the 1950s and 1960s to fight. Caputo recalled that as a young man he dreamed of “charging up some beachhead like John Wayne … then coming home a suntanned warrior with medals on my chest.”1

There is no doubt that Hollywood rallied to the American war effort in the early 1940s and offered countless features that stressed not only the nobility of the struggle but also the patriotism and virtue of the Americans who served their nation. To a large extent the collective import of these films glossed over the grim realities of war as well and the injury and pain it brought to people everywhere. There was some break in the nearly mythical depiction of the war in the later part of the forties. Films such as The Story of GI Joe (1945), The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), and Home of the Brave (1949) offered a more sobering perspective on the war and its tragic elements but did not directly contest the value of the struggle itself. For decades after 1945 Hollywood continued to produce stories that celebrated the gritty determination of the ordinary GI such as Battleground (1949) and the heroic qualities of American military leaders such as The Longest Day (1962) and Patton (1970).

Consequently, most students are somewhat astonished to learn that there was actually a relatively strong tradition among moviemakers to use films about World War II to make powerful antiwar statements—even before America became embroiled in Vietnam. To an extent this project was carried out in a somewhat oblique manner in the first decade or so after the war. Stories like The Men (1950) did this when it focused on the physical and emotional scars soldiers brought home from the war. There were also movies that depicted veterans as dangerous and violent men such as A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), No Down Payment (1957), and film noir features such as Suddenly (1954), in which Frank Sinatra played a veteran who made a living after the war as a hired gun who tried to assassinate the president of the United States.

The critical undertow evident in World War II films became more explicit, however, in the late 1950s and early 1960s when a number of movies began to challenge not only the virtuous view of some Americans who fought in the forties but also the value of any war effort at all. In part, this stemmed from a growing wave of dissent against the massive arms race of the Cold War. Yet, the American experience in World War II was also increasingly challenged by war veterans and others who had experienced the conflict firsthand and now brought to their cultural work countermemories of what they recalled.

Between 1958 and 1964 a number of Hollywood features directly disputed the sentimental view of the American war effort. In 1958 The Young Lions, based on a novel by Irwin Shaw, a war veteran who was blacklisted by Hollywood, offered a story that undermined the American victory celebration. Dean Martin appeared in the film as a young singer who was more interested in avoiding the draft than serving his country. At one point in the film he confides to his girlfriend that he was actually “against war” and the “super patriotic atmosphere” of America. In The War Lover (1962), actor Steve McQueen played an American bomber pilot stationed in England whose character completely reversed the wartime sentimentalism of the 1940s. McQueen’s character was a rugged individualist detached from any sense of morality and justice. He hunted Germans and, for that matter, women with equal enthusiasm. His alter ego in the film, a fellow soldier played by Robert Wagner, could still manage the delicate task of bombing Germans one day and treating women with love and affection the next. It is McQueen’s character, a variant of American identity, that dies at the end, but the film did make the point that some members of the “greatest generation” were not as noble as one might believe. This film, too, was based on the writings of a prominent war correspondent of the 1940s, John Hersey, who had already exposed the capacity of Americans to inflict severe violence on innocent civilians in his 1946 report, Hiroshima.

The Victors (1963) was an especially dark rendition of the American experience in World War II. Directed by Carl Foreman, a war veteran who also worked on the screenplay for Home of the Brave, this story followed American forces through Europe not to relive the victory but to offer a critical perspective on the nature of war and the men who fought. Ironically, although the film exposed many of the sordid details of the contest, it offered very few scenes of actual combat. Instead, audiences could watch American bodies loaded on trucks in Italy and see GIs get drunk or commit a hate crime against their African American comrades. Some of the soldiers even reveal revulsion over the violence they see, especially in a scene that seems to mimic the real wartime execution of an American deserter, Eddie Slovik.

Disparaging perspectives on the Americans and their war effort are sustained in The Americanization of Emily (1964). The story was based on a novel by William Bradford Huie—a Navy veteran who had published a critical account of Slovik’s execution in 1954—which suggested that this common man was executed not only because he was unwilling to fight but also because he was from America’s lower classes.2 In this film an American officer played by James Garner lives a life of privilege in England during the war while attending to the needs of admirals and generals, a reference to a real bone of contention between officers and enlisted men that haunted the military during the 1940s. Garner is cynical about patriotic rhetoric and rationales for war and remarks that millions have been “butchered” in this war and that in the next war “we will have to destroy all of man to preserve his dignity.” Garner meets a woman—played by Julie Andrews—who is gradually “Americanized” through her association with him and comes to accept his view that there is nothing noble in sacrificing for one’s nation. When Garner is finally ordered into the combat zone, his superiors sustain the cynical edge to the film by turning his battle experience into a public relations maneuver for the Navy.

A mythical view of World War II is shattered completely in director Samuel Fuller’s 1980 film, The Big Red One. Fuller was a combat veteran who brought a soldier’s outlook to cultural recollections about the war. He had landed in the third wave on Omaha Beach and recalled seeing dead bodies everywhere. When it came to remembering the war, Fuller resisted strongly any attempt to see it as ennobling and argued that the men who fought only wanted to survive and nothing more. In his autobiography he claimed, in fact, that he had turned down an offer to direct The Longest Day because he felt it was too “overblown” and did not pay sufficient attention to the suffering of soldiers. He carried his memories directly into his 1980 feature that was marked by antiheroic views. In a narrative that follows an American rifle squad through Europe, religious symbols are deployed to suggest that war, far from being a necessary political crusade, was mostly a transgression of basic Christian principles. Some GIs even articulate the view that what they are doing is not destroying an enemy but committing murder.3

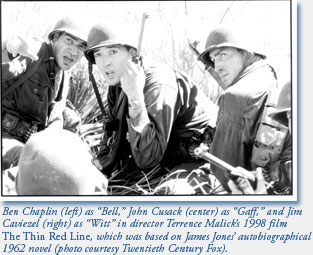

In more recent times movies like The Thin Red Line (1998), which was based on the highly critical view of World War II by ex-soldier James Jones; Flags of Our Fathers (2006); and Letters from Iwo Jima (2006) have continued to raise questions about seeing World War II in highly sentimental terms. This is not to say that there was no value in the American struggle. Certainly the defeat of National Socialism was a justified cause. But these films articulate skepticism not only toward war but American exceptionalism as well, and they express concern that more young people will be influenced the way Caputo was.

Notes

- Philip Caputo, A Rumor of War (New York: Ballantine, 1978), 6. [↩]

- William Bradford Huie, The Execution of Private Slovik (New York: Duell, Sloan, and Pearce, 1954). [↩]

- Samuel Fuller, A Third Face: My Tale of Writing, Fighting, and Filmmaking (New York: Applause Theater and Cinema Books, 2002), 180, 475–83. [↩]

John Bodnar is Chancellor’s Professor of History at Indiana University. He is also the director of the university’s Institute for Advanced Study, and codirector of the Center for Study of History and Memory.