Graduate students coming to the 2019 AHA annual meeting have a host of concerns, but it would be fair to say that the question foremost on many of their minds relates to their career: Will I get an academic job? And from this one question follow others: Will I find myself in overeducation purgatory? Will I be able to find the full-time, tenure-track position for which I will be qualified at the end of this six-year or seven-year—or more—marathon? And will I actually want to live in the city or college town from which the singular offer comes? Will I, like many others before me, have to adjunct or stack up postdocs and continue to live for years in a liminal space until I can finally find a permanent academic and literal home?

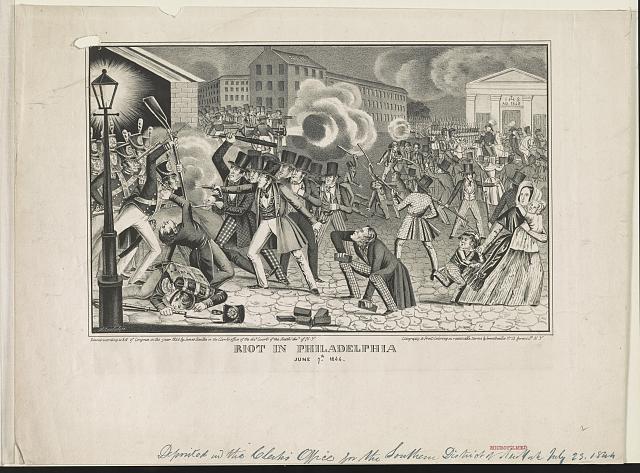

The AHA Career Fair introduces job candidates and students to historians working in nonacademic jobs. Panelists argued that faculty should be preparing students for careers outside academia. Marc Monaghan

Faculty from the fields of history and English argued in the panel “How Do We Fix the Advising Model for Humanities PhD Students?” that failing to properly prepare today’s students for nonacademic jobs is tantamount to malpractice. The four panelists and chair repeatedly used the term “replication” to describe the existing faculty-centered advising model that is more concerned with legacy-building than on training graduate students. This was also the subject of AHA Executive Director James Grossman’s September 2018 Perspectives on History article, “Hierarchy and Needs: How to Dislodge Outdated Notions of Advising.”

Edward Balleisen, panel chair and professor of history at Duke University, asserted that too much academic freedom for faculty, and not enough for graduate students, leads to “abusive advising” that rarely has consequences in academia. Often, added Leonard Cassuto, English professor at Fordham University and author of The Graduate School Mess: What Caused It and How We Can Fix It (2015), associate professors serve as directors of graduate studies or in other capacities that put them in contact with the needs of PhD students. If senior faculty engage in neglectful behavior, they are rarely confronted by junior faculty due to power differentials in their departments.

Cassuto opened the conversation by asking the audience to imagine the numbers 8, 4, 2, and 1. Eight represents an incoming cohort of PhD students. The attrition rate is about 50 percent, so 4 of the 8 will graduate with their PhDs. Those 4 expect to find the same job that their advisers have. But only 2 will get full-time teaching jobs, and only 1 will find the job for which they were trained—that of a full-time, tenure-track faculty member at an R1 research university. About 1/8 of every incoming cohort in the humanities can expect to work in the job for which they were all trained, and the other 7/8 will end up doing something else. That something else adds up to what Cassuto called an “ethical failure” on the part of humanities departments. Right now, the graduate school curriculum in humanities serves 1/8 of us, which he noted was “utterly irrational.”

Balleisen conducted an unofficial census of the room, discovering that the audience was evenly divided among graduate students, faculty, and administrators. This indicated to Balleisen that members of all positions in the academy recognize that something has gone wrong with the decentralized advising model. A decentralized department has few requirements and prides itself on its flexibility, yet the outcome for students is graduate training of highly variable quality. When I was deciding which department to tie my career fate to, I heard many say that their departments were decentralized. Now I recognize that nearly all American humanities departments are, which links our experience as graduate students to our advisers’ inclinations.

What is the way forward?

Rita Chin, professor of history at the University of Michigan, described her department’s team-based approach to mentoring. Students have one adviser in their field of interest, and one outside of it. Michigan created a mentoring committee that offers workshops to departments that request them. Chin has found that inviting faculty to generate ideas of what a quality mentorship looks like yields better results than forcing faculty to create mentorship plans.

At Duke University, Maria LaMonaca Wisdom offers advising support and nonacademic career counseling to humanities PhD students in the two-year-old Versatile Humanists office. She recommended that other universities create similar positions since it can be a lot to ask committee members to teach students about private sector employment opportunities with which they have no familiarity. The panel inspired me to contact Wisdom’s counterpart at my university right away. As I edge closer toward the degree, it seems that it would be negligent on my part to not explore nonacademic career options. Unfortunately, the Zen moment in the PhD program when I imagined I could just tune out the world and singularly focus on my dissertation does not exist. The job search awaits.

Ricardo Ortiz, chair of the English department at Georgetown University, promoted MLA’s Connected Academics program. As with the AHA’s Career Diversity for Historians initiative, it seeks to prepare English doctoral candidates for careers outside of the academy. Georgetown and MLA have both proposed future doctoral programs in the humanities that have less replicating and hierarchical mentorship models. Instead of creating a PhD program in English—which it does not currently have—individual faculty in Ortiz’s department decided to partner with the graduate school to build an interdisciplinary public humanities PhD that trains students in the production of cultural knowledge. Ortiz called this “engaged” or “civic” or “applied” humanities. It is somewhat of a myth that there is a crisis in the humanities, he explained; sure, there are a lack of classic academic jobs, but this does not mean that humanities PhDs are unable to find meaningful work related to their skillsets and interests. Ortiz said that programs need to reimagine reward mechanisms to incentivize the overhaul of ossified faculty cultures.

Though the panel mostly focused on how faculty and administrators can improve the graduate experience, Cassuto told us students in the room: “You are the CEO of your own graduate education.” Here’s hoping I can turn this PhD into a successful enterprise.

Amanda Bosworth is a PhD candidate in history at Cornell University. Her dissertation explores sea-based Russian, American, Canadian, and Native interactions in the North Pacific region influenced by shifting political geographies after the transfer of Alaska.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.