The pages of Perspectives this month are filled with insights and models for using digitized materials and the Internet to teach, learn, research, and communicate. Implicit beneath these articles, however, lies a question about the changing nature of relationships between campuses and national or international locations of activity. This question focuses our attention on both a tension and a promise posed not only by the new technology itself, but also by the changing circumstances in which scholar-teachers (including public historians) find themselves.

From the introduction of the Internet, a truism has been that a fundamental clash of cultures would mark its development, counterposing advocates of the “free” flow of information against those who wanted to control content, in terms of both quality and profit making (or, at the least, cost recovery). This clash no doubt still manifests itself as the ‘net evolves. But the experiments underway that will affect how historians teach, do research, and communicate with others are not characterized especially by this fundamental clash. Rather, they are marked—in their advances as well as their drawbacks—by the extent to which they are confined within the limitations of campus resources and conceptualizations.

This is a promising time in the exploration of alternative modes of creating and disseminating new knowledge, with fascinating experiments underway from which we all will learn. The experiments, however, are limited to a discouraging extent to the teachers and students on a single campus (in the case of courses), or to the content of a single library or archival collection or list content of a single scholarly press (in the case of scholarship). In part these limitations are due to practical issues: controls over intellectual property rights often confine participants within a single licensee’s domain, and it is generally at the campus level that experimenters can most easily convince those who allocate resources that they will be spent to benefit the constituents of that campus. Yet the needs being addressed, and the outcomes of the experiments, will only work to the extent they can reach successfully beyond campus boundaries to the broader community of scholar-teachers (in our case, specifically, historians).

Such an important point has been brought home repeatedly in a series of meetings convened over the last nine months. Taken together, these discussions have highlighted the need to develop standards for mounting digitized materials in ways that serve scholarly and learning interests, rather than commercial developers’ and infotainment concerns. At a roundtable entitled “Computing and the Humanities” (sponsored by the National Research Council); at a conference on the endangered monograph (cosponsored by the American Council of Learned Societies, the American Association of University Presses, and the Association of Research Libraries); and at a weeklong workshop of history journal editors, the fundamental conclusions drawn were very similar:

- With a few notable exceptions, historians are relatively illiterate about what is out there and how it works, and they worry that they will have to invest time and energy in grappling with technology that would be better spent on research or teaching.

- They see an extended period of parallel worlds of past practices (print) and new (electronic) that will affect how well they can create and communicate new knowledge.

- At the same time, this prolonged period of parallel modes of dissemination will make it a more expensive world for those who specialize in disseminating scholarship—and to the extent that this impedes the ability of scholars to have their work distributed and read, it becomes a real threat.

- This extended period of parallel dissemination, given the expense and confusion of multiple formats, must also be a period in which the advantages or values added by digitization have to be made tangible, and must be easily demonstrated.

- There is a flip side to this phenomenon as well: as print diminishes as a mode of communication, or dissemination becomes more “hit and miss” in terms of access, the danger is that the very real strengths of print scholarly communication will be lost—especially the portability, timelessness, fixity, and stand-aloneness of a particular work and the quality control that created it.

Given these concerns, the experiments presented at these meetings were also very interesting. Generally speaking, these experiments have been campus based: in publishing, the experiments all connect to one press (often in partnership with one library, through the campus home). While the campus focus has enabled some very interesting diversity in approaches, the narrow base has led, in turn, to real limitations. There are virtually no ways to move among the experiments. Equally serious, the experiments have been forced to focus on a particular small range of content—what is held in one library, or controlled by one press—and this constraint flies in the face of a national, even international, context for scholarly communication that has emerged naturally around the disciplines.

These limitations matter, and not just for technological reasons. This is a period when real challenges are being presented to previous understandings of how quality is achieved in teaching, research, and public dissemination. Similarly, it is a period when the unevenness of access in one form of dissemination may be exaggerated in another. Technological innovations in these areas, to the extent they are confined to single audiences and locales, cannot address the more fundamental questions emerging about quality and access. If we are to address these challenges, we can only succeed by bringing together the interested parties from campuses and those who have the capacity to work on national and international levels.

We need some experiments that reach beyond campuses, that bring various national and international players to the table. We need to focus one or more of these experiments on materials that address a single, coherent mass of work (for example, a “database” of historical studies, primary source materials, and instructional exercises that enable students to use these materials with some sophistication). We need to reach consensus on how to digitize and disseminate such a critical mass—so that, no matter which press or campus contributes a work, it fits within a larger whole that can be searched, hyperlinked, and so on. We need to involve creative scholars who are not on campuses, and are willing to commit resources. With the explosion of materials on the ‘net, we need ways to measure and ensure quality. Thus we need ways to fashion the most productive partnerships across campus and national or international boundaries, and we need funders with vision to see that this kind of partnership will use their support more cost-effectively and with greater benefit to a larger number of people. Only in this way can we build beyond the single-focus, smaller experiments to create a larger and shared world, shaped to meet the needs felt so broadly.

If we look briefly at three realms in which these needs now manifest themselves, we can see why larger coalitions and partnerships would prove so beneficial. In teaching (both on campuses and in public venues such as museums and historical sites), in research, and in the management of digitized intellectual property, campus experiments can serve as the base, but we need to move to larger collaborations if we are to really benefit from the promises of the new technologies.

Distance learning, to the great concern of many faculty, has been touted as a panacea by many administrators and legislators. They look to the technological innovations in delivery as solutions to two issues—reducing the labor-intensive costs of teaching and reaching dispersed and more diversified student bodies (with “payoffs” for offering this access that are both financial and political). This view of education can only be sustained so long as teaching and learning are defined and framed simply as information delivery. Experiments underway do suggest that, for some adult learners (usually doing postbaccalaureate and often advanced professional preparation), units of distance learning can accomplish the goals desired by administrators. For most undergraduate education, however, the outcome is to be not simply information retrieval but the development of analytical and other skills (summed up in our field by the term “thinking historically”), and this development generally requires interaction with teachers as well as other learners.1 Working through the new technology, then, will require not just the widespread adoption of technologies to improve delivery, but the identification of the elements in quality learning experiences and the careful design of content and exercises that build on these elements of quality.

Campus experiments are beginning to emerge that demonstrate how to put together the new technologies and elements of quality learning. These models are likely to remain isolated, however, in large part because of intellectual property constraints. More crucial still is the fact that it will take a national dialogue to establish guidelines or recognition of best practices that will convince administrators, governing boards, legislators, and accreditors that more than labor relations and self-interest are at work when faculty scrutinize the potential in distance learning.

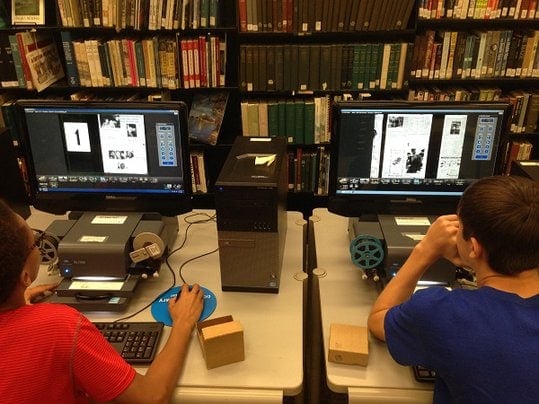

In research, too, the benefits from larger forms of collaboration are evident for two different kinds of efforts. The first relates to the ability to keep scholarly communication alive, especially for small-audience fields where academic presses have retreated because they cannot recover their costs (in history, many of the area studies fields as well as ancient history qualify). In earlier columns I have discussed the potential in a monograph project that enables a number of the actors involved in the dissemination of new knowledge to collaborate, reducing risks and costs for each and maximizing the kinds of contributions each makes to scholarly communication.2 The second benefit from the new technology for research activity relates to new ways to conceptualize historical problems and new capacities to analyze materials. These benefits have been most obvious in the use of searching and similar functions for large bodies of texts, but some very interesting experiments are beginning to emerge with visual materials as well.

In the first case, we need critical masses of materials to make online scholarly communication really useful. This is almost impossible to accomplish on single campuses, for the reasons cited above. In the second case, real advances can only come in the aggregate, with infusions of R and D funding; at present, almost all of the successes to which we can point have required extraordinary individual mastery of the technology and endless entrepreneurship to garner the necessary resources. We need to pool the insights learned from these pioneering projects. At this stage we also need to avoid reinventing the wheel endlessly, from project to project, and campus center to campus center.3 When the kinds of expertise located in such centers and projects can be joined in national collaborations with larger critical masses of materials, we will be able to combine the complementary strengths and knowledge bases to take real steps forward.

The third realm for our attention is that of management and access to intellectual property (a recurring motif in the earlier examples, as well). In the frustrating and ultimately fruitless exercises of CONFU, the commercial interests involved in the infotainment world worked relentlessly to limit access and to assert the profit motive for property rights (despite the clear statements in print copyright legislation that the circulation of information was a more important social goal than remuneration for “ownership” of intellectual property).4 At much the same time, actors from the educational community began to define a balanced world of fair use and cost recovery: these definitions have emerged in policy documents as well as the development of working models for sharing materials while imposing modest fees on use.5 Campuses are beginning to work from their own statements of “Principles,” but these tend to leave out important actors in the larger education world, such as museums and presses (even though these are often located on campuses). Indeed, the contrasts between the campus-focused and national ways that issues are cast and scholarly interests are accommodated may be the clearest illustration we have of the need to reach beyond campus boundaries in our search for new solutions to the problems and potential posed by new technology.

For this is a complex world we now inhabit. As these realms suggest, scholar-teachers have become at once creators, disseminators (or the beneficiaries of disseminators), and users. Experiments limited to a single audience or located within a confined world of content can serve as models to be replicated, but without larger national discussions and forums such as the AHA, we risk having to replicate without linking, to work in isolation instead of building partnerships on complementary functions and expertise.

Notes

- See, for instance, Thomas C. Holt, African-American History (Washington, D.C.: AHA, 1997). [↩]

- See Sandria B. Freitag, “The ‘Endangered Monograph’: Why Aren’t Scholars Lying Awake Worrying?” Perspectives 35:8 (November 1997): 9. [↩]

- Next spring, for the first time, a number of campus centers bringing together computing technology and the humanities will be convened under the aegis of the National Initiative for a Networked Cultural Heritage and partners. It is an interesting commentary that these groups have never met before. [↩]

- CONFU is the Commerce Department’s two-year Conference on Fair Use. See Sandria B. Freitag, “High Stakes: The Future of Scholarly Communication,” Perspectives 35:7 (October 1997): 5. [↩]

- The National Humanities Alliance’s statement of the “Basic Principles for Managing Intellectual Property in the Digital Environment” provides one of the best examples of the policy documents being crafted. The Museum Educational Site Licensing project illustrates the way that differing institutional needs and interests can be reconciled when all of the actors subscribe to the same shared values. [↩]