In a July 21, 2004, communication to Susan Collins, chair of the Senate Government Affairs Committee, the president and executive director of the AHA expressed the Association’s deep concern over procedures being followed in the nomination of Allen Weinstein to lead the National Archives and Records Administration as the Archivist of the United States (see the text of the letter).

Why is the AHA concerned?

The first seeds of unease were sown when the White House suddenly announced (on April 8, 2004) the nomination of a new archivist without having held the customary consultations with interested parties as required by the spirit, if not the letter, of the National Archives and Records Administration Act of 1984 (Public Law 98-497). Readers will recollect from a report published in the May 2004 issue of Perspectives that the AHA then joined several other organizations (including the Organization of American Historians, the National Humanities Alliance, and the Society of American Archivists, among others) to express concern about the nomination. This concern was deepened by the disclosure at a recent hearing of the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs that White House Counsel Alberto Gonzales had requested the resignation of the current archivist, John Carlin, in December 2003 (see the Coalition Column for a report on the hearing). The 1984 legislation certainly allows the president—who, in fact, appoints the archivist subject to confirmation by the Senate—to appoint a new archivist. But the law also states clearly that when an archivist is being replaced, the president “shall communicate the reasons for such removal to each House of Congress.” To date no reasons have been provided for the White House actions on this nomination. Whether the Senate will act on the confirmation without further information from the White House remains to be seen.

Why does the process of replacing the Archivist of the United States matter?

At one level, it matters simply because the historical profession has to depend on the integrity of the archival record, and that, in turn, depends upon having an archivist who is discernibly above the swirling tides of partisan politics. At another level, the independence of the office of Archivist of the United States (and the integrity of the National Archives) matters also because it is crucial to all citizens, a necessity acknowledged by the Archives Act of 1984 in its stipulation that the archivist “shall be appointed without regard to political affiliations.”

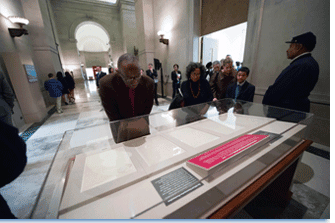

Citizens depend on the National Archives to maintain military and social security records; even more, they expect it to preserve and protect the story of the nation contained in the millions of documents housed in the National Archives’ many repositories, including the numerous presidential libraries that the archives manages. Confidence in the integrity of the archives is an essential precursor for the credibility of the many biographies and histories that draw upon these documents and which an eager public so avidly consumes. Such confidence was a necessary foundation, for example, of the John F. Kennedy Assassination Act, which answered conspiracy theorists by declassifying 4 million pages of its records relating to the murder of the president. More recently, the opening of records on the Holocaust have led to greater justice for thousands of victims and better understanding of those terrible events for survivors’ families and for us all. The role of the National Archives in preserving and making accessible to the public records of the 9/11 Commission will be no less critical.

Recognizing the importance of the National Archives, the AHA has not only been closely involved in its creation in the 1930s, but has been actively engaged since then in ensuring that it remains above arbitrary political considerations. It is for this reason that the AHA supported the 1984 legislation, and it for this reason that the Association is concerned now.

Like the heads of a number of other independent federal agencies, the Archivist of the United States has an important but difficult job, complicated as it is by changes in technology and the ever-present need to balance budgets. But unlike the others, the archivist is also the prime keeper of the nation’s memory. The process of appointment of a new archivist should reflect the seriousness of that special responsibility.