Editor’s Note: As the AHA prepares to enter its 126th year, we conclude the special series of 125th anniversary Timelines articles with an analysis of the changing demographics of its membership in its first six decades. We will continue to publish in the Timelines column notes and articles offering glimpses into the history of the AHA and of the profession. We also welcome submissions from readers for the column.

The establishment of the American Historical Association in 1884 is often marked as the start of modern or professional history in the United States. So peering more closely at who was in and who was out of the membership in the early days of the AHA can provide a useful frame of reference for the larger historical enterprise.

The following analysis of AHA’s membership draws on a database of information about 15,156 AHA members, history doctoral candidates, and PhDs, supplemented (where possible) with additional biographical and census data.1

Viewed broadly, over the Association’s first 60 years, membership grew 13 fold—from 220 charter members in 1884 to 3,229 members by 1941. But membership growth was not consistent—it could rise and fall by as much as 10 to 20 percent in a two-year span—and often tended to be tied to the publications available as member benefits—the Annual Report beginning in 1889, the American Historical Review in 1898, and The History Teacher in 1911.

Those with a professional interest in the discipline—principally in postsecondary education, but also in high school teaching and a number of other areas that would now take the label of “public history”—tended to renew year after year throughout their careers. But such members constituted only about half of the membership through much of this period.

A large segment of the membership had only an a vocational interest in history, and could be quite fickle in difficult economic times. Significant drops in membership tended to accompany economic declines, political controversies in the Association (such as the charges of corruption leveled at the AHR editorial board and the Council between 1916 and 1917), and the elimination of some publications as member benefits.

The Geography of the AHA

Despite aspirations to be a “truly national organization,” the AHA drew most of its membership from the northeastern United States for reasons that were as much practical as cultural. The day-to-day leadership of the organization has traditionally been located in or near Washington D.C. and most of the organization’s membership and meetings between 1884 and 1920 were between New York and D.C.

This generated a significant amount of tension with scholars in other areas of the country. Reading through the AHA papers, the list of those who felt excluded from the activities of the Association at one time or another included faculty from Harvard University (who resented leadership from Johns Hopkins University and the prevalence of meetings in Washington, D.C.), southerners (who established a short-lived Southern History Association in 1896), and historians west of the Mississippi (who were responsible for the establishment of the Pacific Coast Branch in 1904 and the Mississippi Valley Historical Association in 1907).

Up to the 1920s, many of the AHA’s committees were constituted with a form of geographical affirmative action—typically by selecting a member from the Northeast, South, and Midwest or West to secure an inter-regional balance. But efforts to appoint historians from the West, such as Frederick Jackson Turner (at Wisconsin) and Fred Morrow Fling (at Nebraska) demonstrated many of the practical impediments to increasing membership outside the Northeast. Turner frequently lamented the effort and cost of the trip from Wisconsin. Similarly, after he was elected to the Council in 1910, Fred Fling found a number of his proposals to Council were stymied because he could not travel to the meetings and his letters did not arrive in time for consideration.

Although the Association could claim members in all the states and territories by 1911, its membership came predominantly from the Northeast until well after middle of the 20th century.

Measuring Membership by the Degrees

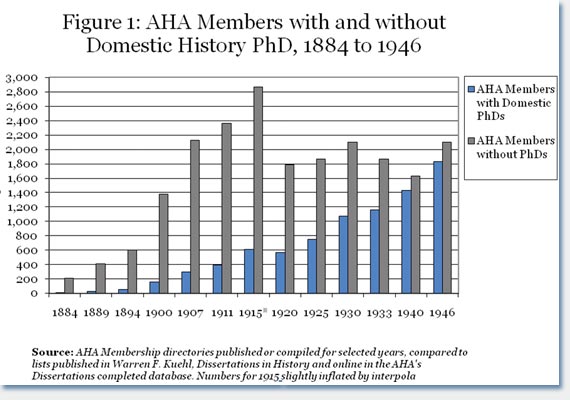

Figure 1

While the history PhD is taken for granted as an essential credential of membership in the history profession today, it was not until the middle of the 20th century that members with a history PhD approached parity in the membership with those without the degree. A considerable amount of the fluctuation in the membership over time was caused by shifts among the non-PhDs (Figure 1).

The PhD was much more prevalent among those who held leadership positions in the AHA, but even so, only about half of the Council and committee members held the degree as late as 1915—rising to a little over 75 percent in 1925 and holding there until after the Second World War.

Beyond the PhD as the endpoint of studies, one can also detect an interesting change in the other degrees members were receiving throughout this period. The earned degrees among those in the leadership slowly shifted away from traditional professional degrees—particularly in law and religion. By 1905 their degrees were largely the more traditional bachelor of arts degrees, reflecting the shift from a view of education focused on preparation for specific professional careers toward general liberal arts education among those attracted to history.

But at the margins a number of new professional degrees began feeding into the disciplinary pipeline. Starting around 1915, a small but significant number of the members on AHA committees held degrees in education or library science, reflecting the growth in newly professionalized activities that were part of the historical enterprise.

This trend is also apparent among the earlier baccalaureate and master’s level degrees for many PhD recipients (recorded in the AHA’s lists of dissertations in progress), as a growing proportion of doctoral candidates earned their undergraduate degrees in teachers colleges and normal schools. While this was a relatively small change, it suggests some of the differentiation of professional work taking place in the discipline.

Areas of Employment

The AHA is often seen as the special province of academics; but in the first 60 years of its existence the members and leaders of the Association were more likely to be employed outside of academia. While 80 percent or more of the members in the Modern Languages and American Philosophical associations were academics, through much of this period, less than a third of the AHA membership was employed in a college or university.2

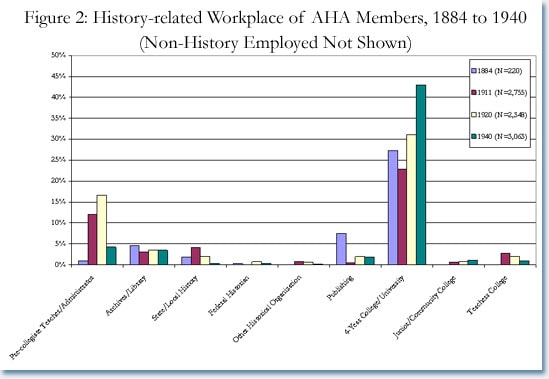

Figure 2

In addition to showing the unusual characteristics of the AHA as a disciplinary society, employment data published in some AHA membership rosters demonstrates the diversity of the employment picture for history between 1884 and 1940 (Figure 2).

While academics comprised a significant portion of the membership at the start—accounting for 28 percent of the charter members of the AHA—their representation in the membership fell off as the Association expanded its mission to include other areas of historical activity and attracted members employed elsewhere. This led to an increase in those engaged in some kind of historical activity for a living—whether as teachers, archivists, librarians, or working for a historical society or museum. As a result, the proportion of academics in the membership declined to just 23 percent of the total membership in 1911.

Precollegiate teaching was a particularly important area of membership growth in this early period, particularly after the AHA adopted The History Teacher magazine in 1911. In that year, 12 percent of the membership was identified as working in K–12 teaching, and this was accompanied by a sharp increase in memberships from faculty and administrators involved in preparing precollegiate teachers (who accounted for another 3 percent of the membership). Those employed in the area of K–12 education rose to more than 17 percent of the membership by 1920.

Outside of the educational fields, almost 10 percent of the membership identified themselves as working in some aspect of library or archival work, publishing (as authors, editors, or publishers), or other history-related work. Given the way the question was framed in 1911—asking only for an “official position”—these figures excluded a large number of independent historians.

Beyond the members who were history professionals (Figure 2), almost half of the members had a largely avocational interest in history work, drawing their living from work in business, politics, religion, and the military. Regardless of their occupations, a significant number of them were published authors (often of the kinds of local and family histories the AHA was thought to disdain).3

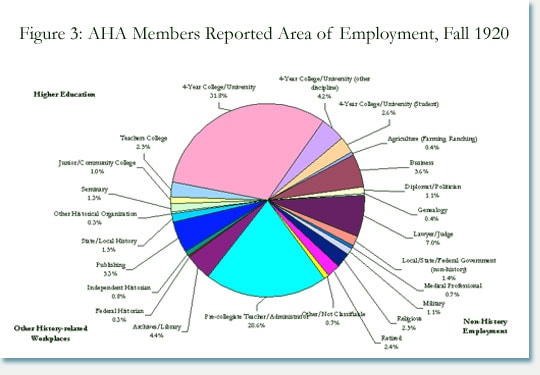

Figure 3

The employment picture for AHA members became much clearer in 1920 since the survey encompassed all forms of employment and historical work and almost 81 percent of the membership provided the requested information (Figure 3).

Excluding those who did not provide employment information, employees at universities and four-year colleges comprised almost 40 percent of the respondents to the survey. Of these, only 32.8 percent could be identified as history faculty. An additional 4.2 percent identified themselves as specialists in another discipline (including other humanities, social sciences, and professional fields), while another 2.6 percent of the respondents reported they were students—typically graduate students. Those employed in some aspect of precollegiate teaching (either as teachers and administrators or as faculty at teachers colleges) comprised almost a quarter of the membership.

Other types of history-related employment accounted for 14 percent of the membership. Notably, there had been a significant amount of erosion in the proportion of members working in some aspect of state and local history, as they began to gravitate into other orbits of professional activity that were developing at the time.

Unfortunately, no further demographic data is available for the AHA until 1940. That survey elicited a smaller response rate (just 61 percent), but it demonstrates the substantial shift toward academics prior to the war. Academics comprised 42 percent of the total membership roster. In real terms, the number of identified faculty at four-year colleges and universities doubled over that 20-year span (from 681 to 1,293) while the total membership increased by less than one-third.

While the academics were on the rise, the proportion of precollegiate educators was falling substantially—from 17 percent to just 7 percent of the total membership. Their numbers dropped by almost 66 percent, from 389 in 1920 to just 131 in 1940. Conversely, a number of other employment areas showed rather telling increases, even if they were too small to show substantial shifts on the graphs. Of particular note is the increase in those who classified themselves as federal historians; their numbers more than doubled as a result of new employment opportunities that became available under the New Deal.

Diversity in the AHA

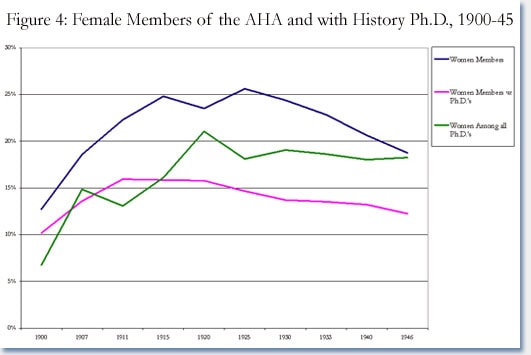

The data available in the various reports suggest that “diversity” was not seen as a crucial issue in the early years of the AHA. Women, for example, accounted for barely 2.5 percent of the charter members in the Association, rose to just over a quarter of the membership in the mid-1920s, and then lost ground steadily from the 1930s into the 1960s (Figure 4).4

Figure 4

The fact that women received little welcome in the history profession throughout this period has been amply documented, as women were excluded from a number of the Association’s activities, such as “smokers” and gatherings at all-male clubs.5 Even though women received a few committee appointments in the first 30 years of the Association, there was never more than one woman on any particular committee and a woman would not be elected to the AHA’s governing Council until 1915.

Nevertheless, even though the proportion of women members in the AHA was quite low, their representation was relatively high when compared to the segment of women receiving history PhDs. Women accounted for 24.4 percent of the AHA membership between 1884 and 1947, as compared to just 16.9 percent of those who received history PhDs.

Women with history PhDs began to abandon the AHA well before the postwar influx of male PhDs. The number of women with PhD degrees in the AHA started falling after 1920, even while their proportion among history PhDs was holding fairly steady. By 1946, the proportion of women in the membership and the proportion among those receiving the PhD was similar, at about 18 percent. The proportion of women members with PhDs, however, had fallen below 13 percent.

A closer look at the employment patterns of women members of the AHA provides a useful barometer. Among the four women on the 1885 membership list, only one woman was employed in an academic setting (Katherine Coman at Wellesley College), two of the others were school teachers, and the fourth listed herself as “Author Writing Books” on the 1910 census. In the 1920 membership roster, women appeared in most of the employment categories, but comprised a majority in just two—genealogy and precollegiate teaching—where they accounted for about 60 percent in each category. They comprised just 13.7 percent of the four-year college and university faculty in the membership at this time. Twenty years later, women comprised 14.4 percent of the four-year faculty in the membership, but their representation among the ranks of student members had declined by a third. Drawing from data collected in 1942, one set of researchers reported that, “Women who took the PhD in history hold poorer positions, are more likely to be unemployed, and are less likely to do research than men. Moreover, the historical profession awards less recognition to its women members.”6 Women thus found themselves in a precarious position in the historical enterprise, and increasingly abandoned by the Association as the discipline became more centered on academic notions of professional employment.

The representation of racial minorities in the AHA was incomparably smaller. A few notable names, like W.E.B. Du Bois, Booker T. Washington, and Carter Woodson appear in the AHA membership rosters, but they constitute only a small fraction of the many other notable African American historians of the period.7

In almost every case their time in the AHA was brief. Du Bois quit after only a year, though he did return to the membership briefly 60 years later. Woodson joined shortly after he received his PhD, but left in 1933 as he began focusing most of his attention on the Association for Negro Life and History.8 The others who appear in Earle Thorpe’s book on black historians only joined for five years or less.

As in the case with women, the Association, which often met in restricted clubs and segregated cities, undoubtedly limited the organization’s appeal, as was the AHR’s policy over lowercasing the word “Negro.”9 African Americans were excluded from the leadership of the Association as well. In a sample of 150 AHA members with appointive offices during this period, census records recorded all of them as white.

Conclusion

The data suggests that the AHA in its early years was not very different from other professional associations of the time and remained through its first 60 years an imperfect vehicle for the realization of the lofty goals proclaimed in its charter. It was only the tectonic shifts of the postwar world that began to transform—if slowly—the profile of the typical AHA member and thus the ever-changing pie charts of the Association’s membership.

Notes

- This essay is based on research conducted for and material in Robert B. Townsend, “Making History: Scholarship and Professionalization in the Discipline, 1880–1940” (PhD dissertation, George Mason University, 2009). We hope to make the underlying data available on the AHA web site sometime in the near future. [↩]

- Laurence Veysey, “The Plural Organized Worlds of the Humanities,” in Alexandra Oleson and John Voss, eds.,The Organization of Knowledge in Modern America, 1860–1920 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976), 71 and 76–78. [↩]

- From information available in the National Cyclopedia of American Biography, ArchiveGrid.com, and the catalogs of the Library of Congress, it appears that a number of these early members of the Association had one or more published books to their credit (although a number of them were self-published). A large segment of those identified as being in the publishing field in 1884 includes a number of journalists—including the AHA’s first treasurer, Clarence Bowen, who received one of Yale University’s first history PhDs and spent most of his career as editor of The Independent—as well as also two members who listed their occupations as “writer of history” on the 1890 census. [↩]

- Willie Lee Rose, Patricia Albjerg Graham, Hanna Grey, Carl Schorske, and Page Smith, Report of the American Historical Association Committee on the Status of Women (Washington, D.C.: American Historical Association, 1970). [↩]

- Joan Wallach Scott, “American Women Historians, 1884–1984,” Gender and the Politics of History (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 178–93; Jacqueline Goggin, “Challenging Sexual Discrimination in the Historical Profession: Women Historians and the American Historical Association, 1890–1940,” American Historical Review, 97:3 (June 1992), 769–802; and Julie Des Jardins, Women and the Historical Enterprise in America, 1880–1945, 37–42. [↩]

- William B. Hesseltine and Louis Kaplan, “Women Doctors of Philosophy in History,” Journal of Higher Education, 14:5 (May 1943), 254–59. [↩]

- Earl E. Thorpe,Black Historians: A Critique (: William Morrow and Co., 1969). [↩]

- Jacqueline Anne Goggin, Carter G. Woodson: A Life in Black History (Southern Biography) (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997), 108ff. [↩]

- David Levering Lewis, W. E. B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 1868–1919 (Owl Books, 1994), 383–85; Fitzpatrick, History’s Memory, 91–97; and Jacqueline Goggin, “Countering White Racist Scholarship: Carter G. Woodson and The Journal of Negro History,” The Journal of Negro History, 68: 4 (Autumn 1983), 356–357. [↩]