At the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana in Venice, just a few feet from Piazza San Marco, where thousands of tourists come each day to pose for pictures and eat gelato, sits a manuscript—Codice Marciano It. XI, 66—containing an invaluable account of a crucial diplomatic mission to Egypt from the 16th century. I consulted this text, which holds the only surviving version of Giovanni Danese’s eyewitness report of Ambassador Benedetto Sanudo’s embassy to the sultan in 1503. Danese, Sanudo’s personal secretary, has left us a wealth of information on the materially based forms of diplomacy that helped maintain a stable relationship between Venetians and Mamluks in the early modern period.

Glazed jar with songbirds, Mamluk (Syria), 14th century. The Mamluks would have given jars such as these to the Venetians. The David Collection, Copenhagen; inventory number 6/2006; photograph by Pernille Klemp

The date of this source, I would suggest, makes it enormously valuable because it offers a window into those relations during the first years of the 16th century, the exact time when the long-distance trading network that linked Venice to Cairo—the spice trade—entered a period of crisis. Following a series of Portuguese incursions into the Indian Ocean spearheaded by Vasco da Gama, the quality and quantity of pepper and other exotic goods flowing through the Red Sea into Egypt and Syria had become much less stable. European consumers no longer needed to go through Venetian suppliers, since Portugal could now offer the same products at competitive prices. This did not change the attitude of the sultan, Qansuh al-Ghuri, who insisted that the Venetian merchants pay more for his spices as his own supplies decreased in the face of Portuguese piracy. It was this state of affairs that contributed to the dispatch of Ambassador Sanudo, whose success in negotiating a new trade treaty with the sultan was due in part to the elaborate sets of gifts he brought to the Mamluk court. Put simply, these gifts ameliorated tensions and helped to normalize relations between the two powers at a time of heightening tensions over the pepper trade.

Length of velvet with artichoke, leaf, and flower patterns, Venetian, late 15th century. The Venetians gave ornate fabrics such as this to the Mamluks, who used them in the production of elaborate ceremonial robes. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The sheer quantity of goods that Sanudo offered the sultan was enormous. Danese reported that the Venetians brought gold, purple, and scarlet cloth and silks of diverse colors, in addition to some 60 robes and 3,120 furs. Production of colorful high-quality textiles, it should be emphasized, involved accessing multiple supply lines and summoning together rare resources. Animal pelts, too, required connections with distant northern European markets, sometimes as far away as the Baltic. By the same token, the sultan sent back gifts to the doge that were composed of equally scarce materials of far-flung provenance: 26 pieces of porcelain, two types of incense, 4 horns of civet musk, and 50 loaves of sugar. The gifts, in my reading of the source, demonstrated the continued vitality of both parties’ international trading networks (in spite of the triumphs of foreign rivals such as the Portuguese), and tacitly expressed their mutual reliance on one another in obtaining commodities that gave them social credibility and bolstered the authority of their regimes.

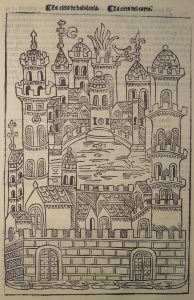

View of Cairo, woodcut, from Il Viazo da Venezia al sancto Iherusalem of Niccolò da Poggibonsi, published 1500. Fondazione Giorgio Cini, San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice

Alongside such sumptuous gifts, however, food also served as a less costly and more immediately useful present. When Sanudo first arrived in Cairo, the sultan sent his entourage 32 lambs; 102 chickens; 40 cakes of sugar, honey, and butter; and a great jug of syrup, as well as nectarines, apricots, apples, and watermelons. It seems reasonable to conclude that food given to guests of state served as an important starting point from which to begin more intense negotiations. For their part, the Venetians reciprocated these donations with their own edible gifts: some 40 pieces of cheese. They brought a particularly high-quality variety, piacentinu, which derived its name from its pleasing taste. This was a peppered goat cheese infused with saffron as a flavorful preservative that also lent it a special golden hue. Piacentinu was regularly served at celebrations held by the highest members of the Mamluk regime. Thus, as with the furs and fabrics, there was in part a straightforward and practical aspect to the gift, in terms of simply offering a Western commodity that the recipients enjoyed. At the same time, however, piacentinu possessed a deeper symbolic significance. Saffron, the most expensive spice in the world, would have greatly amplified the degree of respect being paid to the recipient, while the added fact that this particular cheese contained whole peppercorns, which were at the very foundation of the trade relationship between Venetians and Mamluks, would have further underscored the importance of their alliance.

Window display at the Drogheria Mascari. 500 years later, pepper and other spices from Asia are still for sale in Venice at the Rialto Bridge. Photograph by

Whereas the divide between Christendom and the Dar al-Islam are commonly assumed to have been impermeable in the Middle Ages and early modern periods, the record of Danese and similar sources show that this was clearly not the case. The gifts, tailored to meet the desires of the recipient while also making silent statements about economic interdependence, demonstrate not only that regular diplomatic contact between Christian and Muslim powers occurred, but also suggest a degree of strikingly intimate familiarity that was relatively unhindered by religious considerations.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.