When Melania Trump donned a pith helmet on her 2018 trip to Kenya—one of four African countries she visited during her first official solo trip abroad—commentators pointed out that her choice to wear the colonial-era throwback was tone deaf and smacked of nostalgia for a time characterized not only by sartorial oddities, but by brutality and plunder. Others observed that it was consistent with her husband’s white supremacist governing ideology, which, by extension, she represents as First Lady. Predictably, there were those who dismissed criticism of Trump’s colonial millinery as liberal hysteria.

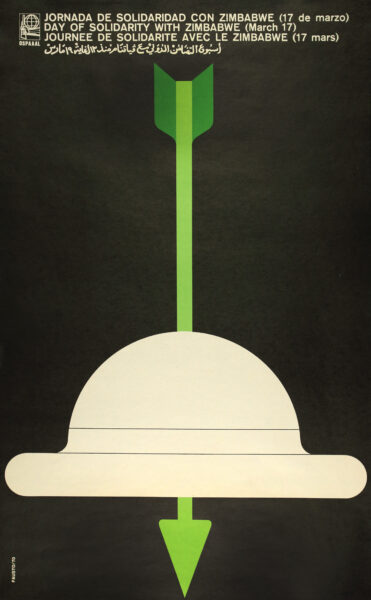

Poster by Faustino Pérez (OSPAAAL), 1970; image courtesy

When I saw the photograph of Trump on safari perched in the back of a Land Cruiser with the white hat sitting atop her hair, my mind raced to an altogether different rendering of the pith helmet—one that I encountered in a secondhand bookstore in Old Havana. In this poster, the pith helmet’s distinctive shape and crisp white color are brought into stark relief against a solid black background, which amplifies the bright green arrow that pierces the helmet. The iconography is unequivocal: DOWN WITH SETTLER COLONIAL RULE! Designed by Cuban artist Faustino Pérez, the poster demonstrates why the “it’s just a hat” defense doesn’t hold water. The spare but powerful image is so fiercely anticolonial because the pith helmet is so quintessentially colonial. Produced in 1970 by Cuba’s Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa, and Latin America—better known as OSPAAAL—the poster commemorates March 17 as the Jornada de Solidaridad con Zimbabwe, or the Day of Solidarity with Zimbabwe. The African population of what was then known as Southern Rhodesia was still a decade away from achieving independence from white settler colonial rule, but Pérez purposefully recognized the name they claimed for themselves, Zimbabwe, and paid homage to their ongoing liberation struggle, one of the bloodiest in Africa’s history.

Although the pith helmet was a favorite of Cecil Rhodes, who famously declared his intention to establish a contiguous British imperial footprint from “the Cape to Cairo,” it wasn’t just a staple of white Rhodesian settlers. By the mid-19th century, it was standard-issue for Europeans fanning out across Europe’s second empires in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. Its material origin is found in India, where pith—spongy tissue in the inner stem of vascular swamp plants—was dried and shaped into the helmet’s iconic shape before being covered with white cloth. Pith was later replaced by cork, a more durable alternative.

While the pith helmet forms part of the sartorial culture of colonialism in ways that underscore just how linked fashion and power always are, its historical roots in 19th-century scientific racism point to a telling paradox: anxieties over white colonial fragility lurked just beneath the surface of this archetypal symbol of colonial power. The pith helmet and other protective devices like the spine pad were meant to shield Europeans in the colonies from so-called tropical solar radiation, which was thought to have deleterious effects on their nervous systems. By the early 20th century these allegedly heat-induced afflictions came to be known as tropical neurasthenia, a “whites only” condition, which lost its scientific purchase by World War II. The pith helmet’s appearance on the war’s battlefields, and nearly 80 years later on Melania Trump’s head in Kenya, underscores its symbolic power, which has outlived the ailments it was supposed to ward off. It also reminds us that the colonial past remains ever present.

Carina Ray is associate professor in African and African American studies, and H. Coplan Chair of Social Sciences at Brandeis University. She tweets @Sankaralives.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.