Most Americans, when asked to imagine a United States National Park, likely picture the red bands of rock in the Grand Canyon, the geysers in Yellowstone, or the granite cliffs in Yosemite. The National Park Service (NPS) is best known for its management of landscapes like these, yet only 63 of the 433 places protected by the agency fit this image. Over half of the Park Service units preserve historically significant individuals, events, or activities. Some of these historic sites seem to have little in common with the great natural parks. Manassas National Battlefield, for example, is surrounded by suburban development. Ford’s Theater National Historic Site, a museum and performance stage, is part of a downtown tourist district, around the corner from a lululemon store. Nonetheless, the Park Service preservation of historic places evolved logically from the early history of the National Park Service. Shifting management of historic sites and monuments to the agency helped streamline and reform a sprawling government and clarified the purpose and mission of the National Park Service.

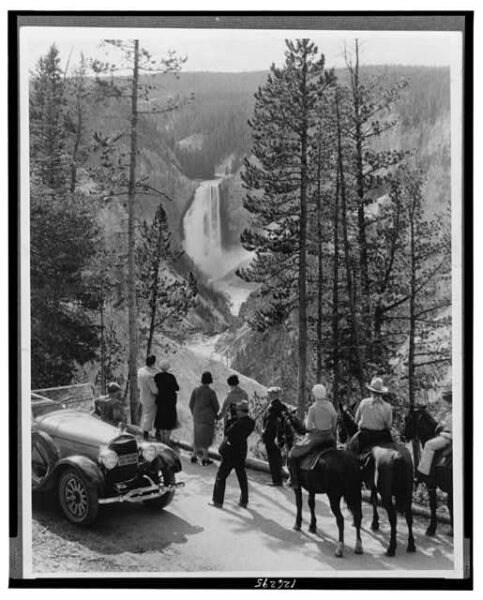

What makes a national park, what is a national park for, and what is the foundation of park management? All questions the nascent National Park Service wrestled with in the early 20th century. Yellowstone Canyon and Great Fall, Wyoming, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, public domain

After the Civil War, the federal government sponsored surveys of the American West to document sources of mineral wealth, demonstrate US military might, and collect specimens to advance US scientific research. Photographers and writers for national magazines accompanied the survey teams, publishing stories and carefully framing images to present the western landscape as wild and untouched by human hands. These narratives excited popular interest and bolstered growing pressures from railroad magnates, hoteliers, and other entrepreneurs for federal protections that would limit development and prevent settlement. The idea of restricting individual ownership of these lands seemed to contradict US emphasis on personal freedom and to endanger the need to establish towns and cities across the continent. But the formal survey reports, drafted by geologists and other scientists, helped ease political doubts. They declared vast tracks of land in Wyoming and Montana “useless” for agriculture or mining. These lands were, however, ripe for the creation of a new kind of industry: tourism. The combined efforts of artists, scientists, businessmen, politicians, and local boosters, then, encouraged the passage of Congressional Acts creating the first scenic parks in the United States—Yellowstone in 1872, Yosemite and Sequoia in 1890, Mount Rainer in 1899, Crater Lake in 1902. Each contained similar language identifying specific areas to be, as in the case of Yellowstone, “reserved and withdrawn from settlement, occupancy, or sale under the laws of the United States and dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.”

Had photographers, scientists, and local boosters only encountered scenic beauty or geologically unique spaces, “enjoyment” alone may have been sufficient justification for each National Park. But as survey teams traversed the West, they encountered entirely different sources of wonder and curiosity. Petroglyphs, pueblos, cliff dwellings, and other structures provided evidence of human habitation predating European colonization and cast doubt on the idea that any wilderness had remained pristine. By the late 19th century, many of these structures had been damaged by westward migrants and curiosity seekers, who chipped pieces off human-made structures and absconded with artifacts from homes and in graves, both ancient and recent. Scientists sounded the alarm and sought to document these critical ruins across the west. Their efforts helped build a professional infrastructure for American ethnology and lent new legitimacy to American archaeology and anthropology, fields previously defined by the study of the European world.

Working under the auspices of newly established scientific institutes, scholars began to press for protections to vulnerable archaeological sites. With a coalition of scientists, local historians, and political figures behind him, Edgar Lee Hewett drafted the American Antiquities Act and helped propel it through Congress in 1906. This law created a quicker process for the protection of sites or landscapes by allowing the president to designate by executive order “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated upon the lands owned or controlled by the Government of the United States to be national monuments.” Notably, it was the first law to identify “historic” structures as worthy of federal protections. Yet the act was not terribly effective at protecting Indigenous structures. It simply distinguished official research from unofficial looting by allowing permit holders from museums or universities to conduct excavations and collect specimens. Once research was complete, the act ordered permit holders to deposit excavated materials in a federally recognized collection. Museums benefitted far more from the passage of the Antiquities Act than did local people or proponents of landscape preservation.

The American Antiquities Act was the first law to identify “historic” structures as worthy of federal protections.

Nonetheless, both Congress and presidents continued to act to advance preservation. By 1916 they had designated 20 national monuments and 11 national parks. As more sites and landscapes were “reserved and withdrawn from settlement,” reformers began to call for a clear statement of standards for national parks and monuments. They also pushed to streamline the sprawling federal government and clarify the purpose of federal land management. These demands led to the creation of the National Park Service.

Three critical questions—What makes a national park? What is a national park for? And what is the foundation of park management?—ultimately brought historic places to the center of the national park movement. In 1913, newly elected President Woodrow Wilson tapped Franklin Lane to serve as the secretary of the interior. Lane, an attorney who had overseen legal wrangles over natural resources in California, organized a national tour of the parks to address questions of standards, mission, and management. Reports from the tour are credited with convincing Congress to approve establishment of the NPS in 1916. The agency’s enabling legislation defines its mission: “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wildlife and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

The work of implementing this mission fell to Horace Albright, the agency’s first assistant director. Albright faced two immediate challenges. First, the NPS had to differentiate itself from other land management agencies, including the Forest Service and the War Department. The dispute between the Forest Service and the Park Service was settled somewhat quickly. The Forest Service advanced pragmatic resource management, while Albright advocated the more romantic ideal of wilderness preservation. The War Department posed a bigger problem. Many historic sites and monuments created under the Antiquities Act had been managed by small land agencies, which gladly transferred them to the National Park Service, but the War Department was reluctant to transfer its historic forts and battlefields. Albright recalled wondering, “Why should a military department be in charge of lands which are predominantly an attraction for all the people? It seems to me that our new bureau ought to be concerned with all areas the Federal Government wishes to preserve and protect for the education, interest and enjoyment of the population.”

Second, the NPS had to demonstrate the national significance of what was largely a regional agency. In 1916, most parks and monuments under the control of the new agency were west of the Mississippi. It seemed unlikely that scenic vistas on par with Yellowstone or Yosemite existed in more developed areas in the east. Addressing both problems required Albright to clarify the mission and expand the holdings of the new agency. The acquisition of historic sites addressed questions of both mission and reach.

Albright toured the parks again in 1917, this time paying attention to the inherent difficulty of meeting the NPS mandate. As he told interviewer Erskine Heine, Albright recognized the requirement “that the parks be protected on the one hand and must be made accessible on the other, creates an inconsistency, a prima-facie inconsistency that can never be gotten around.” Management decisions at individual parks and monuments had exacerbated an inherent contradiction between facilitating visitor enjoyment and ensuring wilderness preservation. Albright addressed this contradiction in a letter he drafted on behalf of Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane: “The educational, as well as the recreational, use of the national parks should be encouraged in every practicable way.” Albright lectured and wrote widely about how education could encourage appropriate enjoyment of the parks. Between 1916 and the end of the 1930s, his recommendations coalesced as the Park Service Creed, which identifies four primary functions for the agency: promotion of health and outdoor recreation, promotion of natural history education, development of patriotism, and advocacy of domestic tourism.

Albright’s most important innovation was to establish education as the core principle of the NPS mission.

When I am asked to imagine a National Park, the first sites that come to mind are Harpers Ferry National Historical Park and Gettysburg National Military Park. While neither is as visually astonishing as Yellowstone, both are lovely, nestled in small towns and surrounded by charming shops and hiking trails. They stand as stellar examples of the Park Service imagined by Horace Albright. Albright sided with reformers who argued natural parks should be protected in as pristine a form as possible. He benefitted from the work of scientists who helped establish historic and archaeological sites as equally worthy of protection. His most important innovation was to establish education as the core principle of the NPS mission. Education lends meaning to historic places and underscores the value of preserving vulnerable landscapes of all kinds.

Denise D. Meringolo is professor and chair of the Department of History at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. She currently serves as president of the National Council on Public History. This essay is adapted from research and writing conducted for Museums, Monuments, and National Parks: Toward a New Genealogy of Public History (Univ. of Massachusetts Press, 2012).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.