In the before times, if you’d asked me if any equipment was necessary for reading, I’d have said a comfy chair. Now? Eye drops. I suspect I’m not the only historian whose reading—however much can be eked out in this grim era—has dramatically shifted from paper to pdf. I also suspect I’m not the only one vexed by the closure of archives and restrictions on libraries. Of course, in the context of a pandemic that has claimed lives, taken jobs, and made childcare impossible, these are minor miseries. But still, the migration of our intellectual life onto screens is miserable.

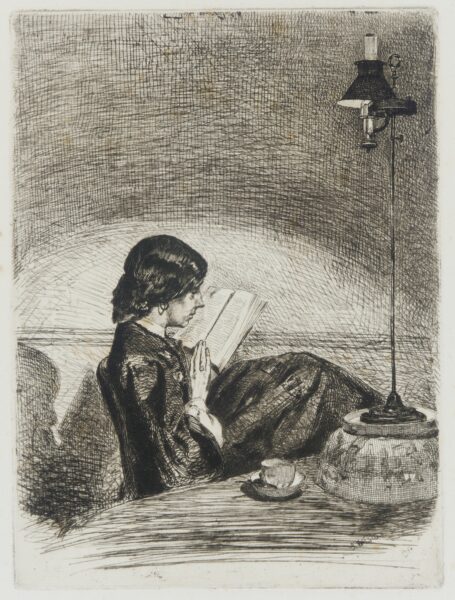

James McNeill Whistler, Reading by Lamplight (1858) Gift of Charles Lang Freer, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Public domain.

My question is whether there’s lemonade to be made from this lemon. For years, digitization has been nudging us away from paper. But we’ve largely resisted, sticking with books as the principal vehicles for our research and archives as the principal sites for it. Now, with archives closed and physical books a luxury, many of us have compensated with digitized sources, HathiTrust, Archive.org, and less-than-entirely-licit means of acquiring books online. The drawbacks are clear enough. Are there benefits?

A cause for hope is recent research by Sam Wineburg and Sarah McGrew. Curious about the inability of experienced internet users to recognize fake news, they ran an experiment on 10 historians teaching at four-year colleges and universities. They sat the scholars down and computers and showed them two online articles about bullying, one on the site of the American Academy of Pediatrics, which is essentially the AHA for pediatricians, and the other on the site of the American College of Pediatricians, a small, “virulently anti-gay” offshoot from the academy that uses shoddy research to promote its agenda. The researchers gave the historians 10 minutes to say which article was the more trustworthy. Half either picked the college’s article or couldn’t decide.

Were the historians bad readers? Not obviously. They did the things we tell our students to do. They read the articles carefully, they looked for citations to refereed journals, they even considered paratextual elements like formatting. The reason for their failure became clear, however, when Wineburg and McGrew ran the same experiment on 10 professional fact-checkers. “Two minutes into our first interview,” Wineburg writes in Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone), it was clear that fact-checkers approached the task differently. “Whereas most of these academics read the Web vertically, their eyes moving up and down the screen as though it were a page of print, fact checkers read laterally, leaping from an unfamiliar site almost immediately and opening up multiple search windows.” Not only did they immediately grasp the difference between the two organizations, they were able to use that context to better interpret the articles. All 10 fact-checkers got the right answer and “none equivocated—even for a second.”

We’re no longer theatergoers sitting in the dark for a two-hour performance; we’re bored teens on YouTube, fast-forwarding, checking the comments, opening more tabs.

When I learned of Wineburg and McGrew’s research, I felt a thud of recognition. I’m an inveterate verticalist, treating each source as a walled garden. Even when reading a recent book, I rarely look up the author. To do so would somehow, I feel, spoil my judgment, as if I were a juror in a high-profile case who needed to avoid the newspaper. I follow footnotes, of course, but serially. Reading with multiple tabs open seems dreadful—one of the great joys of reading is that it doesn’t require being online.

Until now, that is. The shift to screens has made it harder to read a book straight through, but it’s made lateral hops much easier. Skimming a book—relying on its internal architecture to navigate it without reading every word—is onerous when you can’t physically riffle through its pages, but searching by keyword is trivial. Footnotes are similarly annoying in digital books, but Google Scholar is a few keystrokes away. The cumulative effect is to disenchant our documents, to greatly lessen their ability to determine what we read or how. We’re no longer theatergoers sitting in the dark for a two-hour performance; we’re bored teens on YouTube, fast-forwarding, checking the comments, opening more tabs.

And maybe that’s okay. I’ve been surprised by how edifying lateral reading can be if you’re in a subfield where enough has been digitized (and there are clear inequalities to do with time, region, and language that must be acknowledged). Reading laterally won’t help you think through the implications of a complex idea or feel the emotional weight of a text. But if you want to know about New York’s 19th-century oyster cellars, you’re in luck. In an hour, you can have easily consulted 20 sources on the topic, 10 of which no footnote would have pointed you toward. There is a refreshing eclecticism to reading guided by searches rather than citations.

As the power of documents to control our reading erodes, our authority as investigators grows.

As the power of documents to control our reading diminishes, our authority as investigators grows. Among literary scholars, there is a well-established movement to supplement close reading with “distant reading,” the sort that can be done using digital searches of large corpora. While close readers scrutinize a few texts carefully, distant readers might compute the frequency of word occurrences in thousands. In this method, it’s not enough for the scholar to read the expected canon and notice things; she must actively generate queries, or there’ll be nothing to see. Historians, who for the most part already read more extensively and less intensively than literary scholars, have not theorized the transition to digital practices with the same fanfare. Yet it might be time for us to, and to recognize the generative power of questions that do not spring readily from our sources themselves.

No one will look back on 2020–21 as a golden age of historical research. But the question is, have we learned anything we’d like to carry forward into the vaccinated future? For my part, I’ve become less of a verticalist. I engage with more books, but less often read them through. I follow more hunches and jump down more rabbit holes, though at the cost of giving less time to anything that isn’t the topic of my current enthusiasm. I still long for the day when I can sit down in an archive or go shopping in the stacks. But I suspect that, when it comes, I’ll be a different kind of reader—possibly a better one.

Daniel Immerwahr is a professor of history at Northwestern University. He tweets @dimmerwahr.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.