While in Boston we were suffering under the prolonged winter of 2014, the students and instructors in our connected classroom in Dhaka were celebrating the arrival of a hotter-than-usual spring. Two mornings each week last semester, half of our class met in a videoconference room at Tufts, while the other half gathered in a classroom at BRAC University in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Via live video link, I co-taught a course called Bay of Bengal–Flows of Change with two colleagues in Dhaka, Perween Hasan and Iftekhar Iqbal. Although we were on different sides of the globe, we were in the same classroom. At Tufts we sat around a long seminar table that extended toward a large television screen, in which we saw another long seminar table of Dhaka students. At various points during each class, we felt we were sharing the same room.

Our Bay of Bengal course explored the Indian Ocean as a site of globalizing processes from the early modern to contemporary times. We focused on changing modes of imperial statecraft and interregional trade, the expansion and contraction of cultural ecumenes, and the emerging circulations of laborers, commodities, and ideas within colonial capitalist networks of extraction and accumulation.

One teaching goal in this class was to explore how globalization simultaneously creates conjuncture and divergence, through reference to the students’ embodied locations. We wanted to examine this theme not only in theory, but in the very practice of study. In particular, we wanted the students from Tufts and BRACU to weave themselves into each other’s worlds, so that they could reflect on divergence-despite-conjuncture in their embodied personal experience over the course of the semester.

We assigned students a semester-long video assignment that they were to complete in small groups that mixed students from Tufts and BRACU. We gave the students instructions on how to curate and preserve their work in a video repository. They used social media, such as Facebook, to share their academic, interpersonal, and cultural resources. We thought this would create an interactive, self-reflective long-distance classroom.

One student at BRACU, Risana Malik, commented, “Although the distance and time difference affected our team building, working on the video essay with my Tufts teammates didn’t seem to be too different from group work I’ve done with students at BRACU. . . . We talked, we delegated, and we consolidated our work.”1

Neelum Sohail, a student at Tufts, noted, “The cross-cultural exchange and learning brought across different perspectives, and I learned from my colleagues in Bangladesh. . . . Creating a video project with one half of your team living on a different continent made it all the more challenging. But I think that it helped us to articulate our ideas and to refine our research and our message for the video essay.”

We tried to emphasize to our Boston and Dhaka students that any frictions, discontinuities, and differences would be a source of practical, experiential learning about globalization. Both the content and the experience of the class, we hoped, would illuminate the ways that globalization brings together asymmetrical and juxtaposed communities and subjects into integral, interdependent, but also conflicting relationships.

The themes that students chose for their videos touched on religion, cultural diaspora, early modern empires, labor displacement, and migration. But it was the actual practice of putting the videos together across discontinuities of culture and political context that provided a great opportunity for learning. Shehryar Nabi, a student in the Tufts classroom, remarked, “Given the huge differences of culture and political affiliation, I thought it would have been more controversial to talk about some very big issues such as religion and national identity.” We set self-reflection, in particular metacognition, as a key learning objective for the class. Students wrote “work diaries” on a biweekly basis about the progress within their groups, including the interpersonal or conceptual difficulties they were having, as well as unexpected things they learned as they worked with students in a distant classroom. We found that, in their work diaries, students often wrote about the great divide that separated the two classrooms in terms of interpersonal difficulties, conflicting cultural norms around group work and handling deadlines, and different conceptions about how family responsibilities affect school life.

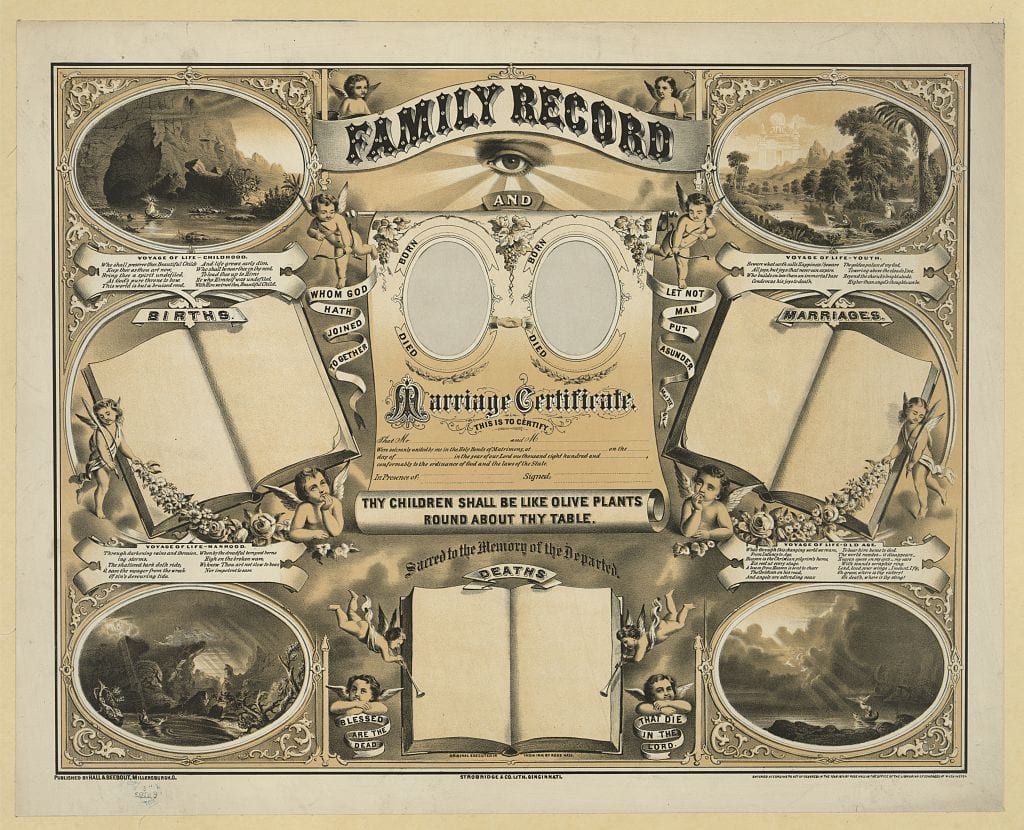

Ahron de Leeuw

“The Buriganga has been Dhaka’s lifeline for more than a thousand years, as a source of livelihood and a means of transportation for its residents,” wrote Abu Bakar Siddique in the Dhaka Tribune on May 2, 2013. Paddle steamers have been navigating the river southwest of the capital of Bangladesh since 1928.

The dialectic of globalization, which entails confrontation and juxtaposition of concrete, embodied differences and the convergence of globe-straddling similarities, was reflected in students’ subjective practical experience within their small groups.

At the end of the course, we carried out two focus groups, one at Tufts and one at BRACU, and also administered written evaluations. At both Tufts and BRACU, the majority of students said that cross-cultural social learning “extremely or to a great extent” deepened their ability to reflect on their own cultural context, their assumptions and values, and their horizons for personal growth.

Students observed that many times it was the disconnections, difficulties, and tensions that arose within the small groups that provided some of the main opportunities for learning during the semester. Mariama Muarif, from BRACU, noted that the long-distance small-group interaction presented challenges, “but we always tried to overlook the distance and helped each other with tremendous support as well as respect.” She added, “There were clashes of thoughts or opinions, as we were from different backgrounds, but we managed to overcome those by being respectful and compromising.” Encounter across boundaries, with a reflective appreciation for the historical and contextual nature of those boundaries, seemed to be of great value to students in both classes. In the focus group discussion, a Tufts student commented, “Despite all my frustrations, at the end of the day it was a really wonderful experience, especially when we watched all our videos at the end. It doesn’t matter who does a bit more work, so long as . . . I experienced a very positive thing—learning something about myself and others.”

Students in both classrooms pointed out that one of the most important requirements for sustaining a long-distance connected classroom is the establishment of trust among students from the outset. A Tufts student insightfully reflected on the difficulties of forming trust online: “The tone of a sentence is completely lost in typing. . . . We found it hard to build interpersonal trust. If such coherence forms, it makes group work easier. After all, even in everyday life, we find ourselves engaging in unnecessary quarrels with people we don’t know very well. That interpersonal connection is really hard.” Shehryar Nabi of Tufts noted, “In an international collaboration, success or failure has more to do with your collaborators than the issue of distance. . . . In order to make it work, everybody needs to care about the project and be understanding of everyone’s situation.”

And this is what is sending us back to the drawing board. For our experiment in long-distance social learning to take the next step, we have to find ways to more effectively build student trust and rapport across the “fifth wall” of the video screen, and across the cultural, historical, and political fault line it constitutes in the classroom.

Last semester, we tried to create rapport by asking students to post bios about themselves, to speak about their extracurricular activities, and to take photos of their local environments and post these on a blog. Students responded positively, saying that these efforts facilitated “bonding.”

But more was needed. Students wanted instructors to play an early leading role in making the cultural and personal contexts around each student more visible to the small-group teams. A BRACU student commented, “The instructor has to set the mood. I think our approach [to learning] is part of our instructors’ enthusiasm. They drive it into us.” Students asked that instructors meet over Skype with the small groups in order to moderate the introductory phase of the video projects. We also have plans to assign more in-class metacognitive exercises that will further cultivate self-reflection and attentive and careful listening to the voices and experiences of others in class. We will need to schedule more class time for students to speak directly to each other in structured ways, using online chat for short sessions of one-on-one interchange between pairs of students across the two class locations.

The global humanities classroom, as it addresses themes of globalization, needs to bridge theory and practice. But to create the dynamic that makes it possible for students to effectively scale and weigh the conjunctures and the divergences at play in their specific embodied interactions with each other, we as instructors must think carefully about how to bring the living contexts of students, their stories, their cultural significations, and their personal meanings into the class setting. We have to find better ways to cultivate a sense of trust and mutual responsibility among students separated by global distances and cultural and historical divides. Once that trust is created, the proper, grounded, experiential study of globalization can begin.

Note

1. Special thanks to Judy Gelman, the editor of the Tufts Arts & Sciences website, for interviewing students and for supplying student quotations used in this article.

Kris Manjapra is associate professor of history and program director of colonialism studies at Tufts University.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.