What is the issue in the May 1993 dispute between the Library of Congress and several justices of the United States Supreme Court over the library’s swift opening of the late Justice Thurgood Marshall’s personal papers, even to journalist-researchers?

These two great institutions are physical neighbors. They face each other across a narrow street on Capitol Hill. Both the Court and the library are fundamentally important, precious national resources. Ultimately both serve the same constituency—the American people—but in differing ways.

As it has for two centuries, the Court often tries to resolve abrasive public issues that presidents, members of congress, or state authorities allegedly mishandled or ignored. And, one of the world’s greatest knowledge depositories, the library, as it has for almost all of America’s national existence, provides senators, representatives, justices, and all researchers with opportunities to reevaluate public issues on the basis of ascertainable facts.

Why, then, the dispute? Its origins are in the written wish of recently deceased Justice Thurgood Marshall to donate his personal papers to the library. Doing so, he honored a tradition, hallowed by major figures in our history, of donating one’s personal papers—one’s private property—to the library or to other archives.

Historians bless this tradition. Among the library’s major magnets for historians are its unequaled manuscript collections. They consist of donors’ unpublished letters, diaries, scrapbooks, and other written items, plus, more recently, transcripts of oral history interviews. Scholars treasure these unedited, often revealing, contemporary documents. After carefully studying their contents against other relevant manuscript and printed sources, researchers can, for example, perhaps correct public officials’ sometimes self-serving versions of events. From 1789 to the present, such versions have existed in published Senate and House proceedings, presidential messages, and to return to the matter at hand, Supreme Court decisions. The historian’s function, in short, is to be a nagging critic even of incumbent public officials if ascertainable facts justify criticism.

From the careful, laborious study of donated personal papers have come some of our most instructive and enduring insights into how the Court’s—that is, the nation’s—decisions in what lawyers call “leading cases” took their shape. Without such documents both history and justice are at best cripplingly blind. Public policies that exclude researchers from access to accumulated contemporary research sources like Justice Marshall’s papers commonly characterize nondemocratic societies.

Justice Marshall followed a well-hewn trail in donating his papers to the library, but, ever a kicker-over-of-traces, he did so in an unusual manner. No party to the present dispute over his papers suggests, however, that when signing his Instrument of Gift to the library, Marshall was mentally or otherwise incapable of making binding decisions about how he wanted his personal property dealt with. Such a suggestion would be contrary to fact and a gross insult to the memory of this acute lifetime lawyer.

The facts are that Marshall’s written Instrument of Gift (a copy appeared in the Washington Post of May 29, 1993), in a brief form and untechnical language, specified the terms of his donation, terms understood by both parties to the transaction. Marshall did not, as many other donors—including justices— had done, stipulate that a certain number of years had to pass or that the demise of all then-sitting high jurists had to occur before researchers should enjoy access. He was untroubled by the fact that the library did not define “researcher” to mean only Ph.D. historians, J.D. attorneys, congressional aides, NAACP activists, any other credentialed calling, or representatives for any purposeful public position or private association.

And so Marshall’s papers went to the library. Presumably—almost certainly—its staff arranged them for use according to the best prevailing standards of the archival profession. And researchers, including journalists, began quickly to use Marshall’s materials, a consequence the late justice, a man wise to the ways of the Washington world, surely anticipated.

They included notes he had kept of the justices’ tightly closeted conference committee deliberations, notes that journalist-researchers have excerpted and placed before readers. These notes are pithy, frequently illuminating, and occasionally amusing. In their extracted form at least, they upset no prevailing understandings of justices’ stands on major public issues. In sum, unless partisanly politicized, Marshall’s papers seem very unlikely to erode scholarly or popular respect for the Court.

It has been a long time since scholarly Court-watchers believed, or justices asserted, that the Court’s decisions resulted only from dispassionate philosophical consistencies or clashing convictions about the intentions of the Constitution’s framers. By detailing the fact that justices shifted voting intentions in pending litigations, Marshall’s notes reaffirm that our robed nobility is, after all, human, and that some justices’ strong interests and personalities influence others.

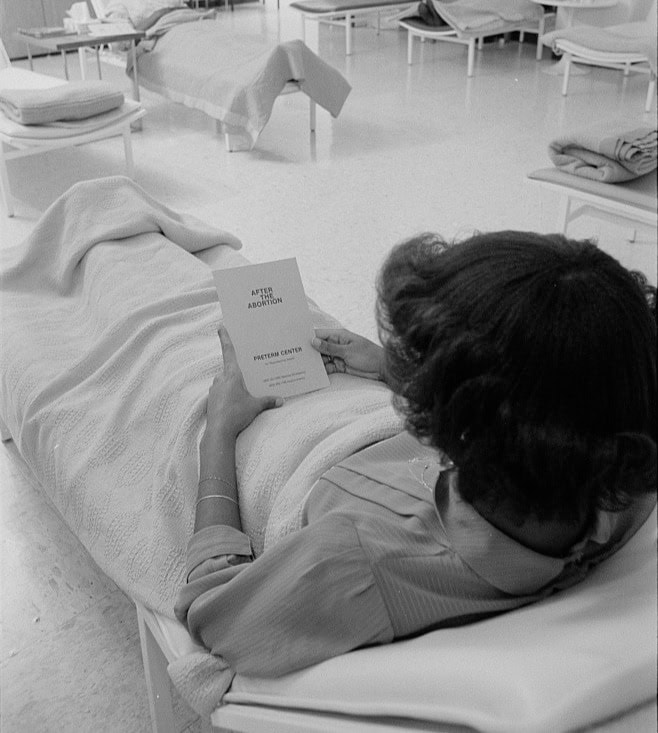

And, to the Court’s credit, the published Marshall excerpts redocument the toughness of the Court’s unending task as a vital third of our check-and-balance national government. That task is to ease the nation’s transit through life’s numerous hazardous twilight zones. In them, for example, as in abortion, religion, or gun control, public laws and private moralities contend, but the Constitution, laws, and precedents provide uncertain guides.

When published in newspapers, excerpts from Marshall’s notes made during the Court’s conference committees outraged Chief Justice of the United States William Rehnquist and an impressive number of associate justices. In strong terms, Rehnquist criticized in the press the library’s swift opening of the Marshall papers to researchers and its broad definition of researcher that included journalists.

An important journalist, Carl Rowan, who, like Marshall, is one of America’s preeminent blacks and who wrote Marshall’s biography, and Marshall’s lawyer, William T. Coleman, Jr., also denounced the library. One effect of their criticisms has been the rekindling of racial undertones heard recently in controversies about Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s donation of his papers to Boston University.

Across broad lawns yet intimately close to both the library and the Court, some members of Congress are attending to the criticisms of the chief justice, Rowan, and Coleman. Efforts may emerge from Congress to require the library to stipulate to donors like Justice Marshall that extended periods of years must pass before researchers can examine donated manuscripts and to exclude journalists from the category of researchers. The first possible policy would violate elementary and properly treasured legal principles about the rights of owners of private property. And the second possible policy would have excluded, among other journalist-researchers, Georges Clemenceau, Walter Lippman, Bob Woodward, Carl Bernstein, William Safire, and Anthony Lewis. Bad ideas, both.

Reasons both obvious and obscure seem to have inspired the justices’ sharp displeasure at the library’s quick opening of the Marshall papers to journalist-researchers. An obvious reason suffuses Chief Justice Rehnquist’s pungent public statement on the library. It is that the court needs to keep absolutely intact its traditional cloak of secrecy over conference committee proceedings.

Yet in the past, including the recent past, some justices themselves have violated this tradition. Paradoxically the tradition endures even in our time of statutory dedication to freedom of information about the formulation and implementation of public policies, a dedication resisted or evaded, however, by other agencies of government in addition to the Court.

The Court’s secrecy tradition perhaps endures in part because historically many justices dislike revelations that what they do is part of governing. Marshall’s notes suggest that the Court’s conference committee sessions reflect many of the tensions exhibited in the White House and Congress. Defenders of the Court’s absolute secrecy tradition assert that the justices can proceed toward supportable decisions only if their deliberations are wholly confidential. Recent presidents who made analogous claims immersed themselves in very hot water.

Which leads to an admittedly obscure reason that perhaps inspired the criticisms of the library made by Chief Justice Rehnquist and his colleagues. In light of Justice Marshall’s position, which was clearly stated in his Instrument of Gift, guesswork about this obscure reason is appropriate. It is that the justices’ criticisms of the library have roots in intellectual carryovers from their pre-judicial law careers.

As law students and practitioners, the present justices, like their predecessors, learned repeatedly that they bore heavy professional responsibilities to protect a client’s confidentiality against intrusive third parties. Attorneys who fail to meet this obligation face awful publicity, damage claims from erstwhile clients, and heavy civil penalties imposed by their colleagues in state bar associations and legislatures. These penalties include suspensions of licenses to practice, or even permanent disbarment.

Are the Court’s present critics of the library applying to their cherished institution’s conference committees professional habits of mind about confidentiality cemented earlier in their careers? If so, perhaps the angry justices should consider some results of their profession’s intellectual baggage, results that a decade ago caused Harvard’s then-law school dean, Derek Bok, to worry publicly that legal education and practice had become seriously flawed.

These flaws have complex causes that go back a long way. Their visible manifestation remains the substantial separation of the intellectual world of law from the rest of knowledge. On university campuses, for example, law schools and law libraries are commonly physically separated from everything else, and arrange curricula, books, periodicals, and other resources differently from other schools and libraries. Distressingly few law libraries want to collect manuscripts even of distinguished lawyers and jurists, or to maintain noncase publications.

Which for a long time forced historians and other scholars to build their studies of the court largely on published high-court case reports that explicitly ignored and implicitly denied that justices’ human attitudes affected decisions. Resulting books and courses almost killed undergraduates’ interest in constitutional history—the kids are smart—and severely limited our understanding of the mysterious science of the law. We know a lot about the formal constitutional side from what high jurists wrote in printed decisions. But we know far less about the law sides, including the often adverse discretionary positions that justices asserted in their closed conference committees. Personal records like those Justice Marshall donated help to enlarge the knowledge.

Legal historians yearn to write no-holds-barred histories of federal and state courts of both lower and higher ranks. But, perhaps like most practicing attorneys, Chief Justice Rehnquist and his like-thinking colleagues are extending their profession’s requirement to protect client confidentiality to exclude outsiders from access to the Court’s inner life.

In sum, the basic fact in the Court-Library controversy is that Justice Marshall knew what he was doing. In clear written terms easily comprehensible by laypeople and law men and women, the late justice chose to give his papers to the Library of Congress. He chose also not to defer access to his papers by any stipulated delay, or to restrict access to journalists or any other specified class of persons. In short, Marshall understood his own permissive intentions and library access policies. Did this fine lawyer need a lawyer in order clearly to state his intentions and understandings?

It is appropriate also to note that important law firms, hospitals, and corporations, who have long asserted the existence of strict confidentiality limitations on third-party access, have recently afforded historians access to their archives, and that no known injuries have resulted to their institutions, clients, or customers. Is the United States Supreme Court so fragile or vulnerable that researchers’ access to justices’ notes of conference committee proceedings will damage this vital institution?

The Supreme Court is a marble palace. But it should not be and has no means to be a self-quarantined intellectual fortress. Nothing yet visible in the printed excerpts from the Marshall papers is shockingly novel or potentially corrosive to the Court’s dignity or authority. But, once politicized, the attack on the library by the chief justice may destabilize his cherished institution more than the publication he deplores.

A further concern is that the present dispute triggered by the Court may raise already too-high barriers between legal historians and lawyers (and jurists), barriers that had seemed to be relaxing. A decade ago, shortly before his death, the young, gifted legal historian Stephen Botein, deeply discouraged at the barriers’ seeming intractability, wrote (in Reviews in American History [1985], 313), “Let lawyers be their own legal historians … and let historians be the same. Once in a while they may have something to say to one another.”

“Once in a while” is now.

Harold M. Hyman is William P. Hobby Professor of American Legal and Constitutional History, Rice University. He is author of, among other books, Equal Justice under Law: Constitutional Developments, 1835–1875 (with W. M. Wiecek, Harper & Row, 1982), and he is president of the American Society for Legal History.