The Tudors are a hot dynasty. This has happened, of course, not thanks to historians of Tudor-Stuart England like me, but thanks to Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Cate Blanchett, Natalie Portman and a range of other 30-something stars who have appeared in recent high profile depictions of the Tudor monarchs. The last decade has seen a veritable Tudor-mania—not just in films and television dramas, but also in historical romances, detective stories, graphic novels, and children’s stories. This is not the first time (nor likely will it be the last) that Americans have discovered the narrative possibilities of 16th-century England. Long before the advent of sound, full-length features explored the lives of Mary Stuart, Anne Boleyn and Elizabeth I. The Execution of Mary Stuart (1895) was one of the earliest silent movies made. The Tudors remained popular as sound films took over in the 1930s, and every 20 years or so since, they have been rediscovered. After the cluster of movies on Tudor subjects in the 1930s, another emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and we are currently a decade into the latest iteration.1 Matching royalty with star power is a long tradition, too: Sarah Bernhardt and Bette Davis have played Elizabeth I; Katherine Hepburn and Vanessa Redgrave have portrayed Mary Stuart; Charles Laughton and Richard Burton have depicted Henry VIII.

The Tudors are a hot dynasty. This has happened, of course, not thanks to historians of Tudor-Stuart England like me, but thanks to Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Cate Blanchett, Natalie Portman and a range of other 30-something stars who have appeared in recent high profile depictions of the Tudor monarchs. The last decade has seen a veritable Tudor-mania—not just in films and television dramas, but also in historical romances, detective stories, graphic novels, and children’s stories. This is not the first time (nor likely will it be the last) that Americans have discovered the narrative possibilities of 16th-century England. Long before the advent of sound, full-length features explored the lives of Mary Stuart, Anne Boleyn and Elizabeth I. The Execution of Mary Stuart (1895) was one of the earliest silent movies made. The Tudors remained popular as sound films took over in the 1930s, and every 20 years or so since, they have been rediscovered. After the cluster of movies on Tudor subjects in the 1930s, another emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and we are currently a decade into the latest iteration.1 Matching royalty with star power is a long tradition, too: Sarah Bernhardt and Bette Davis have played Elizabeth I; Katherine Hepburn and Vanessa Redgrave have portrayed Mary Stuart; Charles Laughton and Richard Burton have depicted Henry VIII.

Tudor history melds the dramas that we associate with monarchy (political intrigue, war, abuse of power) with the domestic plots of family sagas (marriage, fidelity, inheritance). It also features powerful women who struggle with challenges usually reserved for men. But the lure for moviemakers is more than a rich vein of stories, for films about the Tudors work within the “special relationship” that unites the United States and the United Kingdom.2 Until the 1960s, Tudor films were as likely to originate in the United States as in the United Kingdom, and while that reflected U.S. dominance of the industry, it also suggests that even as Americans accepted the conflicted diversity of our beginnings, the anglophile’s dream of lineal descent from a heroic Elizabethan age survived. Apart from a domestic tinge in casting, little else distinguishes where a film was produced—monarchs are the stars; love and betrayal the favored storylines; extravagance the expression of grand passion.

This rich filmography makes it easy to use film to teach early modern English history: the choices are wide; the material details are often authentic, especially in recent efforts; and even for students new to the subject, the language and characters are familiar. However, as the film possibilities have expanded, the role of film in my classrooms has become more complicated. The challenges reach beyond questions of factual verisimilitude, that easy mark guaranteed to encourage discussion and analysis.

Challenge one: how many texts are there in this class? When I was an undergraduate, my cast of movie Tudors was pretty simple: Richard Burton as Henry VIII, Glenda Jackson as Elizabeth I, Genevieve Bujold as Anne Boleyn, Vanessa Redgrave as Mary Stuart, and Paul Scofield as Sir Thomas More (in pretentious moments, I might mention Bette Davis or Charles Laughton). Contrast this with an undergraduate today: she has the current images (Cate Blanchett or Judi Dench, for example, as Elizabeth I), easy access to the most popular older ones (to stick with Elizabeth: Glenda Jackson, Bette Davis, Jean Simmons, and Flora Robson), and two recent television Elizabeths as well (Helen Mirren and Anne-Marie Duff). Students have always come to class with firm ideas drawn from fiction, but now they have multiple visualizations that convince them, on the one hand, that they “know” the history, and on the other hand, that the historically accurate Elizabeth (or Mary, or whoever) is infinitely malleable.

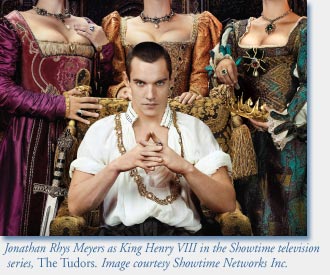

The rise of the television Tudors has complicated matters even more. After an extended gap, both PBS and cable television have recently re-found the narrative potential in Tudor histories. A new drama has appeared annually since 2004, but no fictional account has ever matched the impact of Showtime’s current series, The Tudors.3 What distinguishes The Tudors is its soap opera style—more explicitly sexual, more embedded in modern popular culture (especially via advertising), and more assertive in its conflation of past and present. One season of The Tudors is more than four times as long as most commercially released films, so the format allows for the sort of minor story lines that spark useful historical discussions. I have had students squeeze a lot of history, for example, from the brief appearance of Henry VIII’s illegitimate son in the first season of the series.

Yet the sustained intimacy of an ongoing drama can also drain the strangeness from the past. A student who has followed Jonathan Rhys Meyers’s Henry VIII over breathless weeks—then years—is likely to have strong (and often wrong) ideas about the possibilities of Henrician history. Students are also watching in new ways. While I view most films in the cinema or on television, my students use their laptops or iPhones. Even intimate stories play differently on a screen inches rather than yards wide. And while I watch most films from start to finish, my students, helped by YouTube, studio sites, and other options, often experience films as fragments. While I am following someone else’s narrative, my students are creating their own from bits and pieces. The challenge is to make this diversity work pedagogically. I’ve found it now helps to frame discussions around form as well as content, that is, to talk about why certain plots lend themselves to dramatization, when the video Tudors are most likely to be misleading, and how the imperatives of different media shape presentation and reception.

Challenge two: talking about my generation. All films reflect their intended audiences. The most recent Henrys and Elizabeths are so popular with undergraduates in part because the stories are aimed at their age group. Rhys Meyer is younger than most of his predecessors, as are Cate Blanchett and Anne-Marie Duff. Conflict between love and work, and the struggle for personal autonomy, issues especially pressing for young adults, get far more screen time than do religion, economy, or statecraft. In virtually all of the recent narratives, love and work appear as a tug-of-war; fulfillment in one precludes fulfillment in the other. Even if we move beyond Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, and Mary Stuart to less frequently filmed royals such as Lady Jane Grey or Mary I, relationships offer little joy and less comfort. One would be hard pressed to find in today’s media the sort of pleasure Beth Throgmorton (played by a young Joan Collins) and Walter Raleigh found in each other in The Virgin Queen (1955). Yet preferring “work” is hardly better, as Cate Blanchett’s quasi-embalmed Elizabeth I at the conclusion of her 1998 film clearly showed. Women are particularly badly served. The powerless ones are sexual toys, the powerful ones sexually frustrated. The prevalent tone reflects the cynicism of our age: religion is a convenience; alliances are manipulations; idealism is naïve. These depictions are not wrong, but they are partial, and the difficulty is finding a compelling counter without resurrecting the equally naive comforts of a Paul Scofield defying absolutism in A Man for All Seasons (1966) or a Helena Bonham Carter passionately vowing to reform the coinage in Lady Jane (1986). How can we reinsert larger issues into stories that seem to have become more ideologically impoverished as they have become visually enriched?

Challenge three: Remember, remember, the fifth of November. Given the number of dramas about early modern England, their narrowness is surprising. Apart from Shakespeare in Love (1998), recent films rarely take their focus off the monarchy; apart from the entanglement of Mary Stuart and Elizabeth I, they rarely mention Scotland, much less Wales or Ireland. Earlier generations of films were at least a little more expansive: The Sea Hawk (1940) and Fire over England (1937) take place mostly on the ocean; Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall (1924) focuses on a gentry marriage; Mary of Scotland (1936) ends rather than begins with the Queen’s flight into England. With the exception of The Prince and the Pauper (1937, and later versions), class distinctions have never been much interrogated.

However, the biggest absence is the Stuarts. There are almost as many films about Elizabeth I as about the dynasty that succeeded her. Because Tudor-Stuart history is routinely taught as a single unit, the Stuart black hole implicitly reinscribes the hoary binary of clever Tudors and inept Stuarts. Much of the last three decades of scholarship has been devoted to undoing that dichotomy, but film and television still reinforce it. No doubt inspired by the success of Tudor dramas, filmmakers are now rediscovering the Stuarts, but too often only to use them as fodder for another installment of what we might call “the Tudor plot”—that is, the quest for work/life balance and a stable succession. The Stuart monarchs had many problems, but since neither struggling for one’s identity nor finding an heir was prominent among them, the Tudor plot sits uneasily on Stuart shoulders. The result is usually poor drama about unappealing characters. Films about Charles II, for example, depict him as haunted by the legacy of his parents (The Last King, 2003) or as someone whose values are dangerous to share (Restoration, 1995;The Libertine, 2005). Plots set outside the court are similarly grim; the best of these, V for Vendetta (2005), explores a future dystopia in which the resistance fighters draw inspiration from the 1605 gunpowder plot against James I.

The problem is not the narrative potential of Stuart history, but the awkward fit of Stuart stories with the Tudor plot. The Stuarts did not reenact the family dramas of the Tudors, and their history adapts better to other subjects. Before the recent flurry of Tudor-mania, stories about the Stuarts often made the monarchs themselves mere background. Winstanley (1979), for example, delved into the life of one of England’s first socialists; Forever Amber (1947) offered a sexier version of Moll Flanders; virtually every recent decade has provided a story (not always released in the United States) about some nonroyal caught up in the mid-century’s civil wars. Two miniseries devoted to Stuart subjects (The First Churchills, 1971, By the Sword Divided, 1983, 1985) tried to show history at home as well as at court, on as well as off the battlefield.4

The current bout of Tudor fever may be breaking. Its most recent product, The Other Boleyn Girl (2008), failed commercially; a proposed film on Mary Stuart is apparently on hold; and even Henry VIII will eventually run out of wives. But the issues raised by these films will remain. Students are conversant with more forms of media than I can ever hope to know, much less master (gaming is another example), so teaching these materials has become an exchange of expertise, their expertise on form countered by my expertise on content. It is no longer enough to be comfortable using films and video to talk with students about the importance (or not) of separating fact and fiction. We must now tussle, however awkwardly, with newer, more technical issues, for these, too, have become integral to Tudor-Stuart historiography.

Notes

- Most prominent of these films include The Private Life of Henry VIII, Tudor Rose, Mary of Scotland, Fire over England, The Prince and the Pauper, Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex in the 1930s; A Man for all Seasons, Anne of the Thousand Days, Mary Queen of Scots, and the television miniseries The Six Wives of Henry VIII and Elizabeth R between 1965 and 1975; Elizabeth I, Shakespeare in Love, Elizabeth: the Golden Age, The Other Boleyn Girl, plus new television productions on Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, all within the last decade. [↩]

- As this article went to press, I learned of a new collection of essays that might interest readers: Susan Doran and Thomas S. Freeman, eds., Tudors and Stuarts on Film (2009). [↩]

- Masterpiece Theater showed three historical miniseries in its first season (The First Churchills, The Six Wives of Henry VIII and Elizabeth R), but between 1972 and 2004, only one other (By the Sword Divided). More recently, Henry VII (2004), The Virgin Queen (2005), Elizabeth I (2006),The Tudors (2007~). [↩]

- Examples include The Vicar of Bray (1937); Cardboard Cavalier (1949); The Moonraker (1957); Witchfinder General (1968); Cromwell (1970). A new miniseries in this tradition (The Devil’s Whore) appeared on British television in December 2008. [↩]

Cynthia Herrup is professor of history and law at the University of Southern California.