In a poignant vignette, author Nevada Barr describes a short interchange between a male visitor and a National Park Service (NPS) ranger at Yosemite. With just one hour to tour the park, the man was seeking guidance as to how to spend his time. The ranger gestured, and replied, “Well, I’d go right over there, and I’d sit on that rock, and I’d cry.” I often had a similar (albeit unspoken) response to such questions from visitors during my eight years as a front-line interpretive ranger at Richmond National Battlefield Park (RICH) in Virginia.

Ashley Whitehead Luskey leads a tour of Drewry’s Bluff as part of Civil War Sesquicentennial programming in May 2012. Courtesy Ashley Whitehead Luskey

A park encompassing 14 Civil War battlefields and historic sites and five visitor centers, RICH can be overwhelming to visitors. With history ranging from the Seven Days battles to the Overland Campaign; the Confederacy’s largest iron manufacturer, Tredegar, to its largest hospital, Chimborazo; the Richmond Bread Riots of 1863, to the burning, evacuation, and federal occupation of the city in April 1865—the park serves as an invaluable outdoor classroom for visitors to engage the past in tangible and meaningful ways.

My daily conversations ranged widely. One might cover the military significance of key battles, while the next discussed their political implications on the home front, wartime evolutions in technology and medicine, or the religious beliefs of Civil War soldiers. I led tours and engaged in conversations about soldiers’ letters home; how newspapers shaped public perceptions of battle and of political leaders; and the ways that women of various classes and the enslaved became critical (albeit “unofficial”) political actors during the war. RICH and its rangers have opened powerful windows into the economic, social, political, and cultural underpinnings of a society rooted in the business of human bondage. Furthermore, they have enabled visitors to forge connections between the inner workings of that fledgling nation’s capital to some of the most iconic battles waged on its outskirts. As rangers, we were guardians not only of history but of memory, and we held the voices of the soldiers and the enslaved, the refugees and the politicians, the industrialists and the spies, in our sacred trust. To learn their stories—to tell their stories—was both a privilege and a duty.

My colleagues and I helped visitors locate the ground on which their ancestor took their final steps. I spoke with international visitors on the similarities and differences between our civil war and theirs. And I still reflect on the solemn faces of young US Army officers on staff ride trainings as they overlooked the fields of Cold Harbor, Gaines’ Mill, and Malvern Hill, listening to my interpretation of commanding officers’ leadership decisions and their repercussions on soldiers. We often were told by visitors that “if only they had visited sooner,” or “if only history could always be taught on site,” they would have fallen in love with it far earlier in their life, or that “things today would have made a lot more sense.”

We often were told by visitors that “if only they had visited sooner,” or “if only history could always be taught on site,” they would have fallen in love with it far earlier in their life, or that “things today would have made a lot more sense.”

Youth field trips are a staple of many historic parks’ visitation. I placed original artifacts in children’s hands, taught them to load and “fire” an original 1863 cannon in the Tredegar Iron Works, led them into the muddy trenches of Cold Harbor and Boatswain’s Swamp and read to them the words of soldiers on that ground 150 years ago, and asked them to think about “What would you have done?” These teaching moments cannot be replicated in a classroom or through a book.

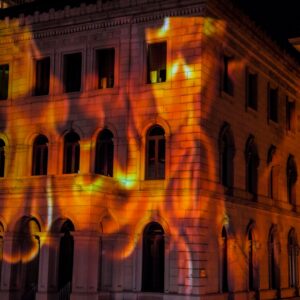

An April 2, 2015, tour of Richmond dramatized the burning of large portions of the Confederate capital at the end of the Civil War, with projections of fire on the buildings surrounding Capitol Square. Courtesy Ashley Whitehead Luskey

Perhaps the most memorable times were real-time tours during the war’s 150th anniversary. We proudly witnessed the breaking down of walls between the NPS and other local cultural institutions; profound partnerships between educators within and outside academia; and the coming together of heritage groups with such very different historical and cultural backgrounds, many who had doubted if they would ever want to share a room, let alone engage in multiyear planning sessions. We saw the complexion, ethnicity, and gender of our visitors expand, our volunteer and “friends” corps blossom, and our local economy flourish. This community “renewal,” of sorts, emerged directly from the unique creative partnerships and new educational programming that the NPS helped spearhead, in conjunction with local businesses, educational institutions, politicians of all stripes, and public-private cooperatives. The NPS was fundamentally helping to reshape and rejuvenate an entire community.

As exciting was when we felt the palpable presence of history. More than 200 enthusiastic visitors followed me through busy downtown streets in the path of the Richmond Bread Rioters of April 2, 1863. Excitement electrified the air as I shepherded hundreds of visitors through the predawn darkness, tracing the US Army’s 2nd Corps line for a “footsteps” tour of the 4:30 a.m. June 3, 1864, assault at Cold Harbor. And a haunting silence permeated the darkness as I guided Virginia governor Terry McAuliffe and his family on an April 2 tour of the 1865 “burnt district.” Every few blocks, that silence was interrupted by living historians portraying terrified civilians, exuberant slaves on the edge of freedom, jubilant federal soldiers, and anxiety-riddled Confederate stragglers; all the while, the giant, flickering flames projected against the backdrop of the city’s buildings quietly illuminated eyewitness accounts of the evacuation fires.

I remember choking back tears with fellow visitors on my June 1, 2014, evening real-time tour as I sprinkled dirt from Litchfield, Connecticut, over the 6th Corps trenches at Cold Harbor; this stop corresponded with the exact moment of the Union breakthrough by the 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery—natives of Litchfield who lost over a quarter of their men in this, their first battle of the war. Our tears fell, knowing that a RICH ranger was simultaneously sprinkling dirt collected from those same trenches over Litchfield’s town green, surrounded by equally somber locals in a luminaria ceremony. I remember observing the profoundly solemn silence two days later, taking in more than 3,000 luminaria dotting the battlefield—each representing a life lost. I recall the tears on the faces of visitors, white and Black, as I read quotes from members of the United States Colored Troops about their march toward Forts Gilmer and Johnson on September 29, 1864, just eight miles outside the Confederate capital. The crowd grew wide-eyed as I reminded them of the soldiers’ acute awareness that, for many of them who had already risked their lives to escape slavery, their freedom and that of four million others was on the firing line that day. Those soldiers understood that capture could mean death or re-enslavement. And yet forward they charged.

In the interpretation division, we were always cognizant that these moments never occurred in a silo.

Each of these unforgettable moments was made possible by the National Park Service, as each was indelibly rooted in the place-based history that is safeguarded and facilitated by the NPS, which forges a powerful, tangible connection between past and present on a highly personal level. But in the interpretation division, we were always cognizant that these moments never occurred in a silo. One of the best parts of my time in the green-and-gray was the deep camaraderie forged with my colleagues. It was a community of individuals who brought diverse strengths and perspectives but who shared a passion and dedication to the NPS mission. We were acutely aware that interpretation could not happen without the park maintenance and facilities staff. Visitors could not safely attend our programming without our law enforcement officers and risk management team. Few people would even know about our park without our communications and IT staff. Thousands of schoolchildren and teachers, near and far, would miss out on critical hands-on learning experiences were it not for our education rangers. And without our natural and cultural resources rangers, there would be few sites left to interpret and visit. Every day, we pulled hard as a team, constantly doing more with less. An absence or a departure of any single ranger from our already short-staffed team, a rescinding of funding from our already underfunded park, a paring of resources in any one division inevitably thundered—not trickled—down through every other division. Today, that thunder echoes ominously throughout the ranks of my former colleagues.

Nevada Barr was prescient in her remarks about the National Parks. Indeed, to have but an hour in a National Park is dismaying, but what happens when there is no longer a National Park to visit? When our natural and cultural resources are no longer valued enough to warrant adequate preservation and interpretation? Although shortages and Spartan times are not a rarity for NPS staff, this new vision is a future few of us in the so-called “forever business” of NPS service could have ever imagined.

If such a vision becomes a reality, I, for one, would be inclined to merely sit on a rock, and sob.

Ashley Whitehead Luskey is assistant director of the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College. She was an NPS park ranger from 2007–15.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.