The stories of some contested objects are simple two-act dramas. They rise. They fall. Certain statues’ stories have third acts. In England, for example, the recently toppled Edward Colston statue has begun a third act in a museum. In Russia, Hungary, and Taiwan, certain Cold War–era monuments’ third acts have involved being placed in “Statue Parks,” sorts of historical theme parks located in Moscow and near Budapest and Taipei, respectively. The Goddess of Democracy statue, first erected in Tiananmen Square in Beijing, has had a more complicated fate. She has had not just a third act but a fourth and a fifth.

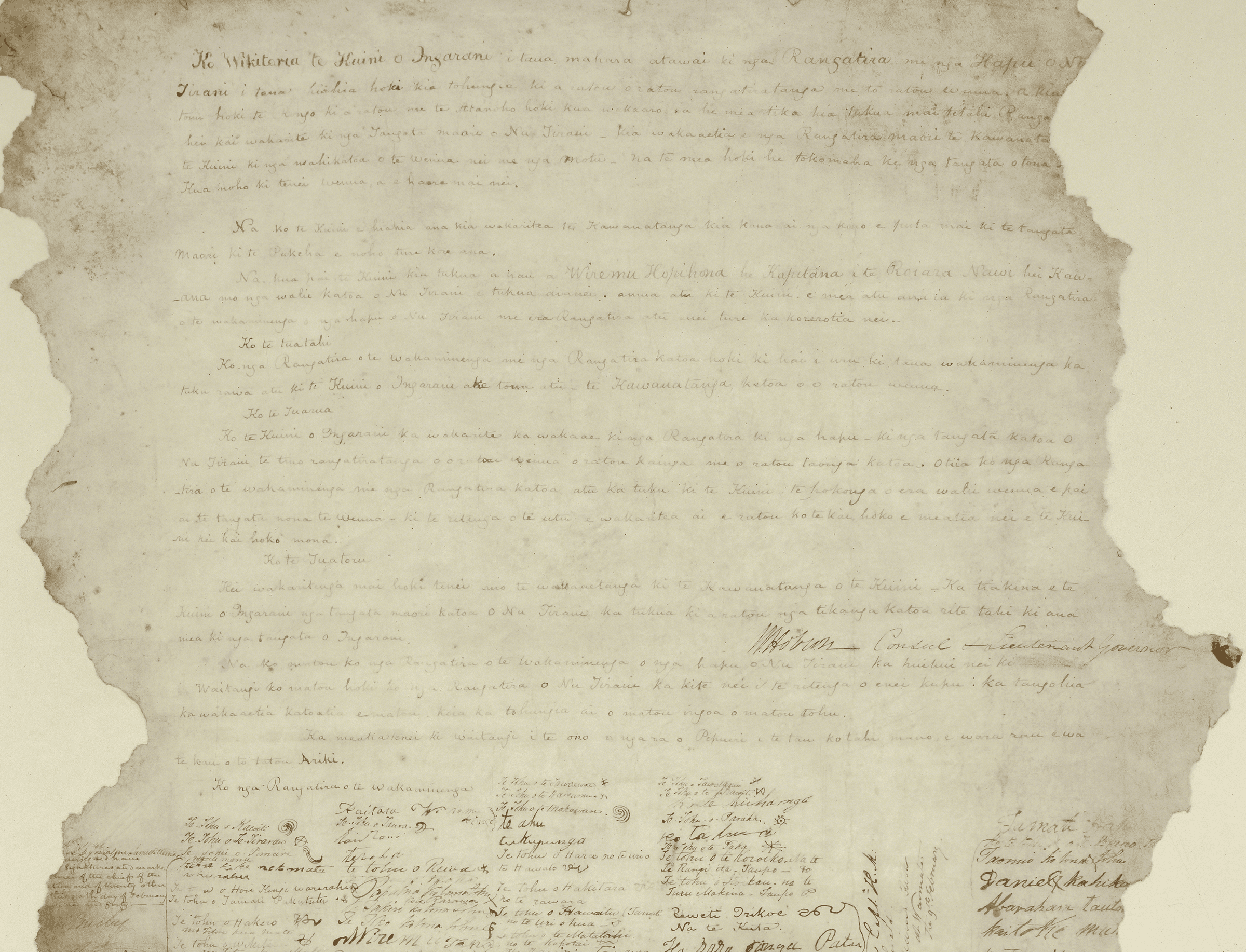

On his visits to Hong Kong, made pilgrimages to visit the replica of the Goddess of Democracy on the Chinese University of Hong Kong campus. Image cropped.

The Goddess of Democracy was knocked down less than a week after she was unveiled during the 1989 Tiananmen protest movement. Her rise and fall were just the first two acts, however, in a tale that continues to this day, and not just in Asia. The story of her brief life and multifaceted afterlife is fascinating for its own sake, but it also alerts us to the varied forms that struggles over monuments can take, as well as what these struggles can reveal about how political orders are challenged and defended.

The Goddess stood 33 feet tall and was constructed out of foam and papier-mâché with a metal armature. She was created by students. This is no surprise. Educated youths played the central role in the massive multiclass, multicity Tiananmen movement—a movement whose participants called for an end to official nepotism and corruption, for increased personal and political freedoms, and for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to do a better job of living up its own professed ideals. The statue fell during the tragic event known in Chinese as the June Fourth Massacre. As a tank toppled the Goddess in the square, soldiers turned nearby streets into killing fields, ending the lives of at least hundreds and likely several thousand unarmed protesters and bystanders.

To make sense of this initial phase in the statue’s story, it is important to understand the meaning of where it occurred. Tiananmen Square is a massive plaza that borders the Forbidden City, which was once the home of emperors. It includes, among other things, the mausoleum of Mao Zedong, the first paramount leader of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and a soaring plinth honoring revolutionary heroes. The base of the plinth has friezes that portray revered historical figures, including the student activists of the hallowed May Fourth Movement of 1919. Participants in that struggle, the most important youth movement of the Republican era (1912–49), included a young Mao and other future CCP founders.

The original has not been housed in a museum or a theme park. She could not be.

Tiananmen is the site of lavish state rituals, such as the National Day parades held annually to commemorate the October 1, 1949, founding of the PRC. These ceremonies celebrate the CCP and present it as the protector of sacred values and the sole legitimate representative of those values. One such value the CCP claims to represent is minzhu, a compound word made up of the characters for “people” and “rule.” Minzhu is generally translated as “democracy,” a term with comparable component parts.

A few weeks before the statue went up in 1989, student activists gathered in front of the plinth’s frieze extolling the 1919 protests and boldly asserted that they, not the country’s current leaders, represented minzhu and other vaunted values of the May Fourth Movement. Their struggle, they said, was a “New May Fourth Movement” launched to put the revolution back on track. The creation and display of the Goddess of Democracy, a white larger-than-life female figure whose name stood for an ideal rather than a powerful individual, also challenged top-down party-centered versions of history.

It is no surprise that the same military action designed to clear the square of protesters purged the plaza of this bottom-up addition to the landscape. The original has not been housed in a museum or a theme park. She could not be. After a tank toppled her, soldiers wielding metal bars destroyed it.

The later acts in this statue story have involved replicas and representations—and global travel, as representations of the Goddess are banned in Beijing. The most important replica, and for a long time the one nearest to Tiananmen, stood some 1,300 miles to the south, on the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) campus. It was one of several important objects with ties to the events of 1989 that once stood in Hong Kong, the former British colony that became a “Special Administrative Region” of the PRC in 1997.

The CUHK Goddess, which was roughly two-thirds as tall as the original and a faux bronze statue, was special to me. It is the only representation of a deity to which, as a person without faith, I have ever made pilgrimages. When I traveled to Hong Kong in the 2010s, I always tried to visit her. It felt special the couple of times I stayed at a hotel right by CUHK and could see her regularly. In part, I always went to see her simply to be sure she was still there, as her days seemed numbered from the start given the CCP leadership’s desire to minimize over time the ways that Hong Kong differed from cities across the border on the mainland. I also wanted to see if anything special had been done to alter her look since the last time I had paid homage. At one point, students added rainbow-colored clothing to the Goddess to link her to Pride celebrations. In 2017, they draped a black-and-white skirt around her, with the names of a hundred or so people arrested for their roles in recent protests written on the white bands—a listing of Hong Kong’s first political prisoners.

The CUHK Goddess was unique—the only large replica of the Beijing statue that existed in any part of the PRC. Simply by standing where she did, she symbolized the fact that there really were special things about this Special Administrative Region. Only in Hong Kong and in nearby Macau, the former Portuguese colony also given SAR status when it became part of the PRC in 1999, could schoolchildren learn in detail about the 1989 protests. Only in those two cities could annual vigils be held to honor Beijing’s June Fourth Massacre martyrs.

The Goddess was rooted in a distinctive point in the past but also represented a desire for a better future. This was signaled by the adornments added to her over the years. Fittingly, in September 2014, when speakers called for CUHK students to join the struggle for democracy that would become known as the Umbrella Movement, many listened while standing or sitting in the shade of the Goddess. And the last time I saw her, in December 2019, she had a placard hanging around her neck with Chinese characters on it meaning “Five Demands and Not One Less,” a slogan protesters were shouting on the streets at the time during marches staged to try to protect those things they felt made the SAR truly special.

Just as the Goddess’s most dramatic third act, the period of replicas, took place in Hong Kong, so, too, did her most dramatic fourth act. This was a repeat, with variations, of the second act. For again the statue was toppled—once more not by protesters but by an autocratic regime—in late December 2021.

As similar as the fates of the original and the CUHK replica were, there are revealing differences. The original was destroyed while a movement was being crushed. Her toppling was caught on film. Briefly it seemed that her falling might become the iconic image of the movement’s end—but then, a day after the June Fourth Massacre, a lone man was photographed standing before a line of tanks.

The Goddess of Democracy drama is now into its fifth act, with events taking place beyond the PRC.

The CUHK Goddess was removed from campus in secret well after a period of repression had begun. There were no cameras to capture the event and no gunfire on nearby streets when she disappeared. She was toppled well into a protracted multistage strangling of a city. This throttling followed and was largely a response to the massive protests of 2019, which began as an effort to push back against a proposed extradition bill that many felt would undermine the rule of law in Hong Kong by allowing the CCP to take local residents to the mainland for trial in courts in which the accused nearly always ended up being convicted. The 2019 movement soon became a fight for the right to protest with a key demand—one of the five referred to in the year’s main slogan—being an independent investigation of widespread police brutality. The CUHK Goddess was toppled almost two years after the last giant Hong Kong protest march took place on New Year’s Day 2020. Eighteen months after Beijing imposed a draconian National Security Law on the city. A year after Apple Daily was closed and its publisher Jimmy Lai jailed.

The Goddess of Democracy drama is now into its fifth act, with events taking place beyond the borders of the PRC. There is no longer any way to commemorate 1989 even in Hong Kong or Macau—or rather no way to do so without risking immediate arrest. The key commemorations now take place in other parts of the world. In the June Fourth vigils now, which take place everywhere from Toronto to Taipei, Hong Kong exiles and references to the city’s 21st-century struggles play important roles, making these events in part commemorations not just of 1989 but also of the 2014–19 protests and their aftermath.

The last time I saw the Goddess was last spring in London’s Trafalgar Square, where I attended a June Fourth commemorative rally that ended with a march to and candlelight vigil outside the London embassy of the PRC. Unlike the Tiananmen original and the CUHK replica, this version of the Goddess was the size of a person—and she moved. Presiding over that rally, which included speeches about what happened in Beijing in 1989 but also presentations by exiles who brought up recent and ongoing repression in settings ranging from Hong Kong to Tibet and Xinjiang, was a young woman dressed as the Goddess.

Jeffrey Wasserstrom is Chancellor’s Professor of History at the University of California, Irvine, and the author of Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink (Columbia Global Reports, 2020). Find him on Bluesky @jwassers.bsky.social.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.