Editor’s Note: This is the second installment in a two-part column. The first column is available here.

It was a summer morning when my husband and I entered a boxed-in room for my green card interview. The immigration officer was friendly but firm. He asked us to raise our right hands and swear to tell the truth. As we sat down, I wondered if the distance between our chairs looked suspiciously wide and if our ironed outfits and organized folders showed we were serious. After the officer took my fingerprints, he asked for proof that our marriage was genuine. We launched into a show-and-tell of our most treasured moments, sharing pictures from our travels. My hand trembled as I handed a photo of us embracing to a stranger who had the power to decide my future. Were we a convincing couple? After a series of follow-up questions, the officer concluded that we in fact were a legitimate husband and wife and told me that a conditional two-year green card would most likely be granted.

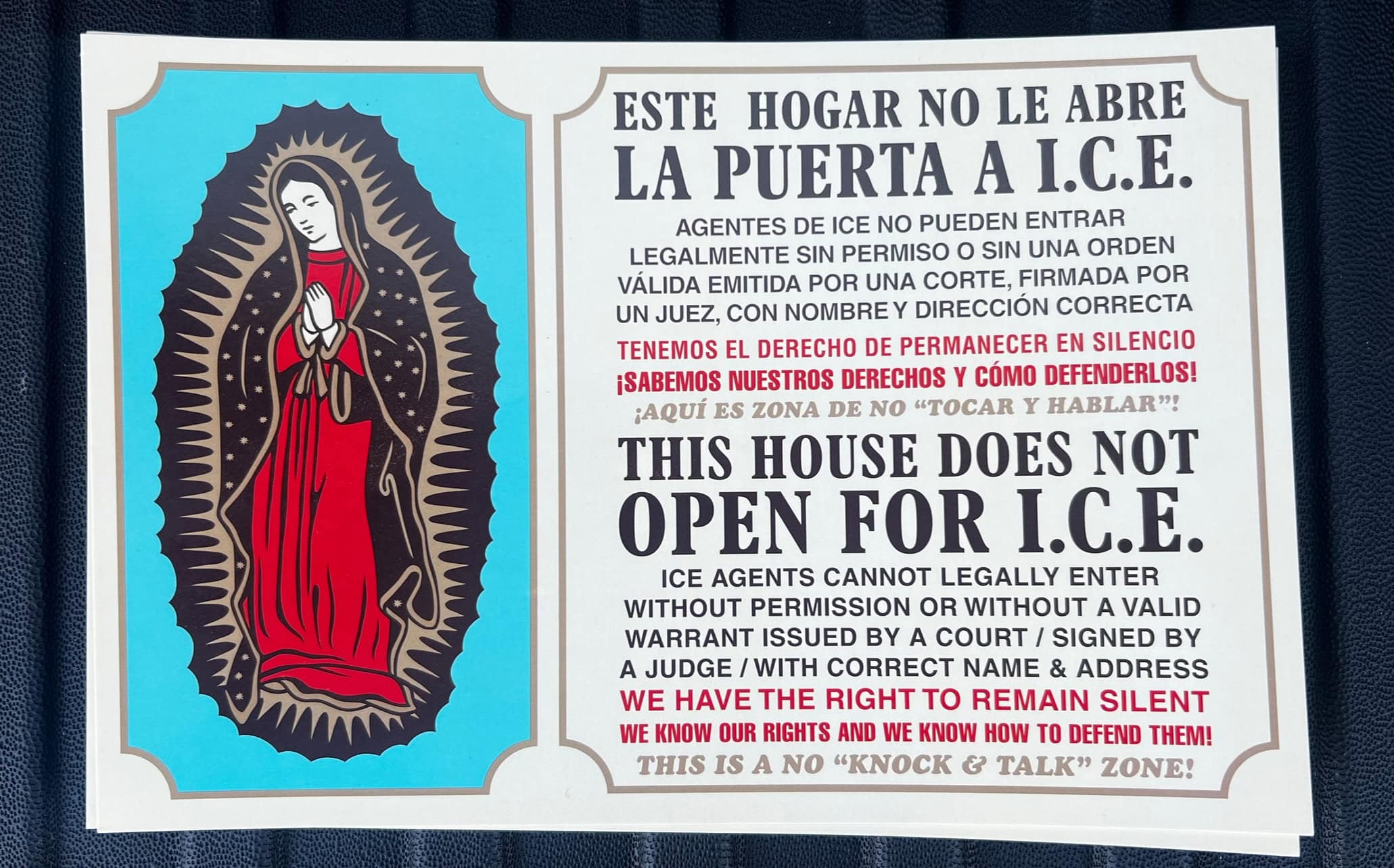

The author and her husband hold evidence of their relationship, as compiled for immigration purposes. Alisa Kuzmina

As I waited for the official notification of approval from US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), I reflected on how my marriage green card application had influenced my perspective as a researcher of Cold War–era immigration. The day I read about the human rights provisions of the Helsinki Final Act (1975), calling for easier visa protocols and lower fees, I stayed up late filing my I-485 form and spent all my savings on the permanent residence application. When I felt frustrated with the endless forms or upset that we couldn’t afford a lawyer’s assistance, I would tell myself that going through this application process in a DIY fashion gave me a better understanding of how binational couples in the 1980s might have felt about immigration-related bureaucracy.

From personal experience I was closely familiar with documents such as Form I-485 and I-130.

There was another, more surprising way that the marriage green card affected my reading of the archive. I experienced it for the first time this summer, when, as a fellow at the University of Minnesota’s Immigration History Research Center, I had the chance to review family reunification cases facilitated by a local immigration assistance program in the late 1980s. One I-130 form I encountered belonged to an American man who submitted it on behalf of his Filipino wife. In the wake of political unrest, the family decided it was safer to relocate from the Philippines to the United States in 1988. It was my first time viewing people’s personal immigration forms, which I previously encountered as an abstract provision in an international human rights agreement. But from personal experience I was closely familiar with documents such as Form I-485 (the adjustment of status) and I-130 (petition for an alien relative, which my husband filed on my behalf). Although the form retains its original name, it has expanded since the 1980 version from a few pages to a dozen.

I sifted through the rest of the couple’s file: scanned love letters, testimonies from friends, and photographs of the couple together by the sea. These were similar to the supplemental documents we gathered to demonstrate the legitimacy of our relationship. This was a dissociating experience of packaging tenderness, ache, and devotion into a neat folder, an experience that belongs both in a Franz Kafka book and Marina Abramović performance art. I wondered if the couple had felt as vulnerable as we did, including pictures of themselves holding hands and embracing; if, perhaps, these were moments they wished to keep to themselves, framed on their bedside table. The couple’s I-130 wasn’t just a stack of dry bureaucratic paperwork; reading it triggered a physical and emotional reaction, a memory of anxiously assembling photographs with my husband for someone to evaluate our compatibility, spending habits, vacation preferences, and conversation patterns.

Reading this file, I felt more attuned to how an anonymous immigration system required the couple to perform the “right” kind of relationship to “qualify” for conditional residency. Tucked inside their case folder was a note from the husband’s lawyer, advising him to provide a letter from his mother expressing her approval of the relationship. His wife was more than a decade older than the petitioner and had a child, which potentially raised suspicions of a fraudulent marriage. His mother’s testimony could greatly strengthen the application. The lawyer’s advice came in the wake of the Immigration Marriage Fraud Amendments of 1986, the predecessor of my own conditional two-year residency. Before I knew it, I let out a “huh?” aloud, startling myself in the stillness of the room. The quiet of the archive peeled open the judgments forming in my mind. I thought about how strange and humiliating it must have been for the couple to involve their family in justifying such personal choices. If anything, the couple had not originally planned on moving to the United States. They envisioned a life together in the Philippines, raising her son and starting a family business.

The continuous logic of bureaucracy turns intimacy into evidence and perpetuates the rhetoric of the green card as a privilege.

Perhaps the most valuable aspect of the overlap between my research and life has been the way it exposed the continuous logic of bureaucracy, which turns intimacy into evidence and perpetuates the rhetoric of the green card as a privilege. I began to see immigration forms as an embodied experience of bureaucracy that enforces a very specific definition of family through paperwork and legal advice. The official instructions for Form I-130 list the types of proof of marriage USCIS will accept—including property ownership, joint finances, and children’s birth certificates—which require a certain level of wealth and social conformity. Our marriage fits none of these criteria, and while it does not make it less valid for us, it makes the immigration process more uncertain and anxiety-inducing.

When I was finally notified by USCIS, it began with the ominous, chest-tightening phrase: “We have taken an action on your case.” Finding out that my conditional green card had been approved was a relief, but it was also a reminder that for two years until the next interview, I will continue to document the validity of my marriage for the state. We will assemble photo albums and collect testimonies from friends, hoping that another official will find our love convincing enough. In the meantime, I will keep working on my research, feeling more attuned to the vulnerability and emotional labor behind the bureaucracy of family reunification.

Alisa Kuzmina is a history PhD candidate at the University of Minnesota and a host on the New Books Network (Russian and Eurasian Studies) podcast. She thanks the people at the University of Minnesota’s Immigration History Research Center and the Immigration History Research Center Archives for their immense help in facilitating her work this summer.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.