For those who study and teach political culture the internet has changed everything.1 Historians trained in the last generation or so understood that political history was far more than simply institutional or electoral history. Studies of “popular political culture” opened up what was until recently described as “political history” by including the influence of nonvoting populations, festivals and parades, and the ways in which cultural memories shape attitudes and identities. Examining how heroes, villains, events, and ideas have been converted into powerful symbols that alternately support and challenge the political status quo is central to the study of political culture. The digital communications revolution in the past decade has made tracing such artifacts of cultural memory infinitely easier. The digitalization of print, manuscript, and graphic materials has moved the traditional archives from fixed locations and has made searching more complete and comprehensive. Beyond the availability of archival resources, the proliferation of blogs and their “comment” sections for visitors extends the possibility of solving some of the most vexing problems of studying collective memory—that of gauging dissemination and reception.

This novel treasure trove for researchers—the internet is, after all, not only the location for digital archives but an archive in itself—also offers new opportunities for teachers to connect students to political history in more effective ways.

Two projects I have used successfully with undergraduate students focus on the memory and memorialization of warfare, and mostly use resources that have become available on the internet. The First World War’s Gallipoli Campaign of 1915–16 offers an opportunity to orient students toward both transnational and comparative elements of cultural memory. The second focuses on the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial to consider both the problems of events still in living memory and the way in which the internet has changed what we think of as the “memorial landscape.” The political necessity of rallying wartime home front support, providing the rationale for war, and defining the nature of the enemy combined with the equally strong postwar imperatives to define the meaning of victory or loss provides, in both instances, clear subjects to follow from construction to dissemination, reception and persistence of a cultural memory.

The Comparative and the Transnational: Gallipoli in Three National Memories

For this project, the student is first introduced to the digitized versions of traditional print sources that show the construction of the story of the Gallipoli Campaign, from the event through its commemoration over the years. Commercial and institutional databases offer newspapers and periodicals not only from metropolitan centers but limited-run, rural, and special interest publications. The scope of these collections allows us to follow not only the speed with which a particular narrative spreads, but to compare its reception in the centers of cultural and political power with that in the hinterlands and the local adaptations that emerge. Following this trail, students can see the meaning Gallipoli came to have for each nation (and for localities within the nation-state) and learn to historicize its use over time. What they learned would not surprise any of the scholars who have charted the memory of Gallipoli over the last century, but for the students it was a revelation to see how the British and the Australian memory of loss differed dramatically, and how the Turks managed to create what one student identified as an “internal and an external narrative” of the Gallipoli Campaign.2

Students found that for the British the “story” in 1916 was one of a political disaster with resignations and reassignments while public attention was directed to Western Front campaigns where equally disastrous losses were offset by victories. For the British, students concluded, there wasn’t much of a “memory” of Gallipoli at all. Following the Australian memory from the first commemoration in 1916 through the present day, students were struck by how central the same battle with the same outcome was to Australian memory and identity. Recent ANZAC Day ceremonies on YouTube, newspaper reports of political speeches, monument construction, national histories, personal web-site tributes, and advertisements for package tours to the graves in Turkey, all charted the development of an enduring and durable cultural memory within its full social and political context over nine decades.3

Perhaps most interesting of the three was the Turkish memory of Gallipoli. Known as Çanakkale to the Turks as members of the victorious Central Powers alliance, it became a rallying point for postwar liberation from Ottoman rule and a foundational element of Turkish nationalism. What particularly intrigued students was the 1934 statement from President Mustafa Kemal Ataturk addressed to “the mothers” of the fallen ANZAC troops. Repeated on stone at the Anzac Cove in Turkey, on a monument to Ataturk in Australia, and seemingly on every web site covering the campaign, it was a reassurance that there was now “no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets…after having lost their lives on this land, they have become our sons as well.” As an example of an explicit use of common memory between nations it showed the importance of attention to historical and political context. The reconciliation of old battlefield enemies within a context of commemoration allowed Turks to frame themselves as victims of their own colonial position in 1915. So, while the Turks were the primary battlefield opponents of the Australians at Gallipoli, they were not fighting as “Turks.”

The Politics of Living Memory: The Vietnam Veterans Memorial

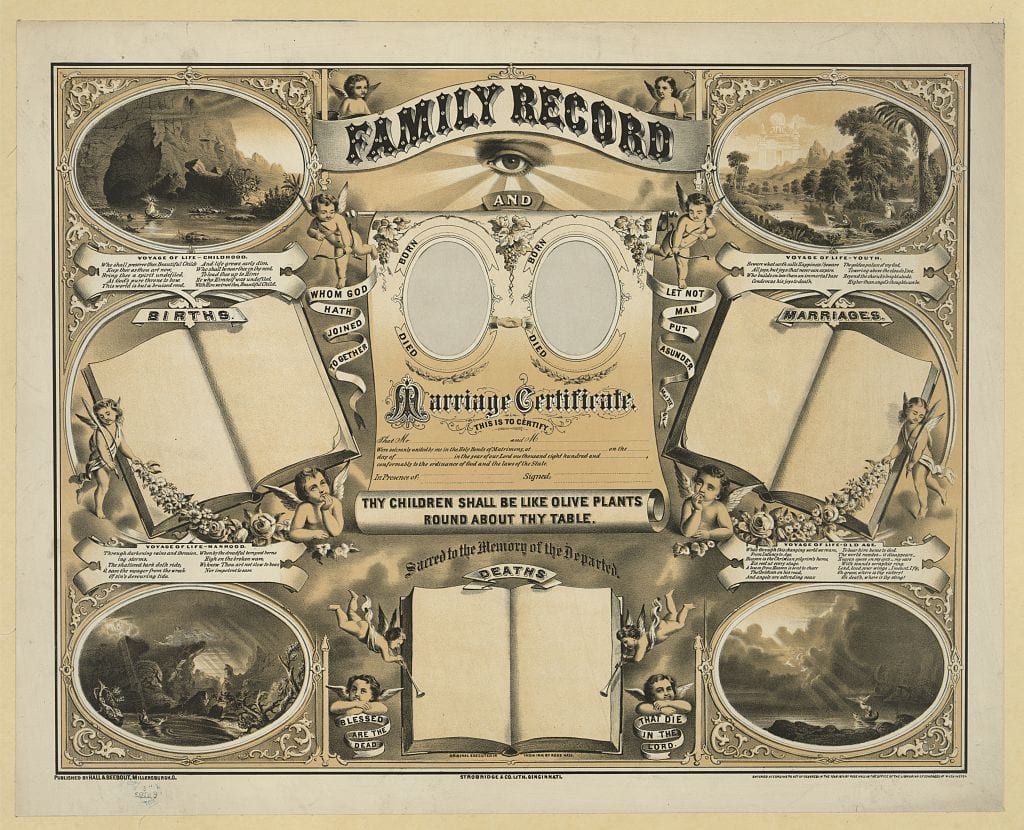

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. Photo courtesy the National Park Service.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., provides a different kind of opportunity for understanding the politics of memory. It allows students to look not only at a more familiar, domestic monument to consider the politics of memorialization of war, but also to witness the dynamic nature of cultural memory as it is struggled over in real time. Still very much in “living memory,” the controversy over the design and location of the memorial in 1982 is less interesting to students than the more accessible and seemingly more relevant ongoing debates. Students discovered in this case not only that the traditional audio, video, and print resources were available in abundance but also that the internet was now not just an archive of sources, but a location of public debate and thus for memorialization itself.

Online projects like “The Virtual Wall” expand the idea of a permanent memorial from the physical to the virtual. This, like most of the similar online projects is a privately constructed and operated site which monitors and censors comments. In the case of the “Virtual Wall,” the community invited to comment is limited “to relatives and friends of the fallen to honor and remember them.” Even within that closed community, there is a warning that “misdirected antiwar sentiment” or comments that are deemed to “insult the fallen or their families by blaming them for the war” will be deleted.4

Looking at online archival projects from another perspective, the Vietnam Center and Archive at Texas Tech University is collecting and making available online oral histories of individuals who were involved on either side and in any capacity. Gathered up to 50 years after service, these are individual memory narratives colored by personal reflection, intervening life experiences, and the passage of time. But, in the aggregate, they map out a path from lived experience to contemporary cultural meaning, even among participants. As a discrete exhibit on the center’s web site, these oral histories are not only an archival resource but become another memorial site.5

Egypt and the Future of Memory

As I was completing this essay, a massive popular uprising against the government began in Egypt. However that is resolved by the time this appears, one of the most critical issues it seems to me is not that it, like many demonstrations in the past few years, is said to be “run on Facebook and Twitter,” but what that means for the ability to chart the evolution of its meaning in Egyptian or in global political memory. Thousands on the scene filmed events on their phones or cameras and as phone and internet access was restored, those images and direct accounts were disseminated online. Messages were texted, e-mails sent, and blogs emerged to provide on-the-ground accounts or to rally international support. Readers commented, and the originators of the posted material replied, making the lines between narrative creators and audiences more blurred than ever. Digital communication is the future of politics but the digital records they leave are also the future of charting the trajectory of cultural memory within political history.

< Previous essay | Next essay >

Notes

- The last decade or so has seen the creation of archives that were meant to be “born digital.” George Mason University’s ambitious project, The September 11 Digital Archive offers a collection of all available voice mails, e-mail and digital ephemera; the project also has a goal of using this event “as a way of assessing how history is being recorded and preserved in the twenty-first century.” https://911digitalarchive.org/index.php. [↩]

- Readers interested in the place of Gallipoli in Australian memory should see: Jenny MacLeod, Reconsidering Gallipoli (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004) and Bart Ziino, A Distant Grief: Australians, War Graves, and the Great War (Crawley, Western Australia: University of Western Australia Press, 2007). [↩]

- In a nice convergence of memory used within other contexts, during the Vietnam War, Australian Eric Bogle’s “And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda” used the voice of a Gallipoli veteran to comment on the futility of war. In 2010 it had another incarnation as the soundtrack for a Canadian student’s “Remembrance Day” project later posted on YouTube. Using images of Canadian military forces from WWI through to recent deployments in the Middle East, Gallipoli functioned as a universal statement about war and in the comments section spawned various arguments about historical accuracy but also about contemporary politics. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WG48Ftsr3OI. [↩]

- Those interested in the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial’s history are directed toward: Kristin Ann Haas, Carried to the Wall: American Memory and the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998) and Marita Sturken,Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, the AIDS Epidemic and the Politics of Remembering (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997). For the Virtual Wall and its policies on comments: https://www.virtualwall.org/docs/faqs.htm. [↩]

- The Vietnam Oral History project is at www.vietnam.ttu.edu/oralhistory. [↩]

Gretchen A. Adams is an associate professor of history at Texas Tech University. She is the author of The Specter of Salem: Remembering the Witch Trials in Nineteenth-Century America (Chicago, 2008).