I recently completed a project with Rocky Mountain PBS, an episode of their Colorado Experience series (www.rmpbs.org/coloradoexperience) on the US and Canadian North American Aerospace Defense Command, better known as NORAD. On the initial conference call, the producers noted that NORAD’s part in the Cold War, especially the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, was of great interest to them. I grimaced slightly, eyed the public affairs officer sitting across the table from me, and then turned my attention back to the trefoil-shaped conference phone. Well, I said, NORAD didn’t exactly do a whole lot during the Cuban Missile Crisis, meaning it did not have a direct role in the confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union. After all, it is a defense command.

This event was one of several that highlighted to me the unusual view I have of the Cold War from my peculiar perch as the NORAD command historian. Historians typically view and teach the Cold War as a decades-long geopolitical, ideological, or strategic event, punctuated with occasional countercultural activities. But from my perspective, the Cold War was an operational experience. Historians in my position emphasize planning, exercising, and resourcing for the air defense, and later ballistic missile attack warning and assessment, of the North American continent. The Cold War, from this historical view, was day-to-day, month-to-month, year-to-year work.

This perspective is far removed from my training as a historian of the 19th-century Southwest borderlands, but I have learned to appreciate it from studying the work of my predecessor, NORAD Command Historian Lydus H. Buss. Along with his deputy Lloyd H. Cornett, Buss completed a study of what they called the Cuban Crisis on February 1, 1963. This study, which dealt simply with what the command was supposed to do, how it did it, and the issues it faced, is a far cry from the large-scale ideological and political narratives we associate today with the Cuban Missile Crisis and the Cold War. NORAD’s mission was to defend the continental United States and the air bases from which any aerial attack on Cuba would be carried out; in the case of an airborne invasion, NORAD would escort paratroop-carrying planes from their bases to a staging area over the Dry Tortugas Islands at the end of the Florida Keys. These plans, as US products, assigned the mission to the Continental Air Defense Command, or CONAD, the joint (Air Force, Army, and Navy) US element of NORAD. This would later cause some friction with the Canadian part of NORAD.

To carry out its mission, NORAD/CONAD had to augment the forces then in Florida, adding over 100 fighters, 4 radar picket destroyers, 18 airborne early-warning aircraft, and 12 batteries of air-defense artillery, all roughly within a week, starting on October 20, 1962. NORAD also had to determine rules of engagement for all these assets, which included a requirement to attempt to divert any Cuban or Soviet aircraft entering US airspace before attacking it. While such issues went undiscussed in the study, NORAD clearly did not want to be the ones to start World War III.

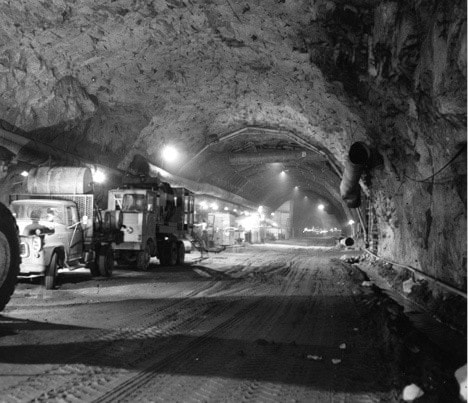

The Air Force digs in. Cheyenne Mountain tunnel construction, April 1962. Photo courtesy of NORAD.

The crisis truly began for NORAD on October 22, when the air-defense forces were ordered to a five-minute alert. NORAD also dispersed 155 interceptors to 20 US bases, a process that took only 5 hours and 40 minutes to complete. Canada, however, had not been consulted on these actions so did not raise its alert levels until two days later and did not disperse any of its aircraft. NORAD thus had 140 fighters in the Montgomery Sector, which included Florida and the eastern Gulf Coast and 715 fighters in the rest of the system, on five-minute alert.

This meant that, for over a month, day and night, maintenance personnel had to check aircraft, identify any problems, and either fix them or bring a backup aircraft onto alert in five minutes. Aircrews had to be briefed and prepared to “scramble” (man the airplane and take off) in five minutes. If a pilot was sick or unable to fly, a replacement had to be ready to go, in five minutes. All this had to be done 24 hours a day, in often austere dispersal bases, some of which lacked heat in the increasingly cool fall of 1962. The logistical and operational planning and preparation to maintain the alert, day after day, speaks volumes of NORAD’s efforts, even if an interceptor was never launched in anger.

After the Soviets had removed the offensive missiles from Cuba, NORAD began to pull back its forces. The dispersal ended on November 17, and the alert for NORAD ended on November 27 (except for Montgomery Sector, which maintained it until December 3). NORAD’s efforts then turned to recovering its forces and regenerating its readiness. On December 3, according to the study, the NORAD commander sent a message “to all concerned,” offering “my congratulations on the efficient and thoroughly professional manner in which NORAD forces reacted to the crisis.”

This quick-turn historical study complete, Buss and Cornett turned to their primary responsibility, the biannual historical summary of NORAD and CONAD, this one covering the period of July to December 1962 and signed by the NORAD commander, US Air Force General John K. Gerhart, on April 1, 1963. The Cuban Crisis, the largest and longest air-defense operation NORAD had ever undertaken, was dispensed with in the first chapter in only six pages, out of a total of 88; the remaining chapter titles show what the command historian thought was historically important during this time: “Organization,” “Manned Bomber Detection Systems,” “Ballistic Missile and Space Weapons Detection Systems,” “NUDET (Nuclear Detonation), Bomb Alarm, and B/C (Biological and Chemical) Reporting Systems,” “Command and Control,” “Weapons,” and “Operations and Procedures.”

Two events covered in the history pointed to the operational future of NORAD, although Buss did not know it at the time. The first was Exercise Sky Shield III, the major air-defense training event, which took place from late at night on September 2, 1962, to early on the morning of September 3. The exercise required the grounding of all commercial, private, and nonparticipating military aircraft in the United States and Canada, although 20 unauthorized flights took place. NORAD used 319 trainers to simulate civilian air traffic that would have to be grounded during an attack. The strike force produced 906 attackers, or “fakers.” The air-defense forces—284 radars, 945 fighters, and 226 air-defense artillery firing units—attempted 1,118 engagements, resulting in only 675 simulated kills. NORAD was disappointed in this outcome, but felt the rules of engagement, which necessarily placed safety first, restricted the opportunity for successful engagements.

While the summary did not note it, NORAD had never been able to achieve more than a 50 percent success rate with the previous two Sky Shields (1960 and 1961). When one nuclear-armed bomber could obliterate one city, this was an unacceptable ratio. But procuring forces and capabilities necessary to increase the likely success of air defense was seen as prohibitively expensive in both Canada and the United States, and many programs had already been canceled. So 1962 was the beginning of the end of NORAD’s emphasis on conventional air defense. The United States had embraced a new strategy for deterrence—mutually assured destruction, or MAD. But, to do this, decision makers had to know when the Soviets had launched their missiles, and attack warning was soon added to NORAD’s original air-defense mission.

This growing requirement was reflected in a small section in the July-January 1962 Historical Summary discussing progress on what would become the iconic symbol of NORAD: the Combat Operations Center being dug into the side of Cheyenne Mountain in Colorado. Excavation, which started in May 1961, was finished by the end of 1962, and internal construction, except for operations and technical areas, was to be completed by July 1964. The operations center would not reach full operational capability until July 1966, but planners added a new attack-warning system terminating inside the mountain.

The study and historical summary leave me with a sense of overwhelming process. The Cold War at the operational level was a massive planning and logistical effort, carried out over decades. For NORAD, the Cuban Missile Crisis appears as only a blip on the larger historical screen—an important blip, to be sure, but still a blip. This is simultaneously reassuring and terrifying—reassuring in that level-headed individuals sought to do their best, terrifying in that they were prepared to do the worst. The United States and the Soviet Union came close to a full-scale nuclear war, but as far as NORAD was concerned, historically speaking, it was just another situation to be dealt with. My view from NORAD suggests that a deeper history of the Cold War exists, one that is operational, organizational, and administrative, that is mundane, to be certain, but quite grounding in its effects because it deals with the realities as they lay at the time. I think Buss and Cornett would be quite pleased if their efforts ultimately contribute to this deeper history. As their successor, I know I would be.

Lance R. Blyth is the command historian of North American Aerospace Defense Command and US Northern Command, Peterson Air Force Base, Colorado. He is also a research associate with the Latin American and Iberian Institute, University of New Mexico. His first book, Chiricahua and Janos: Communities of Violence in the Southwestern Borderlands, 1680-1880 (2012) was awarded the Western History Association’s Weber-Clements Prize for the best nonfiction book on Southwestern America in 2013.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the North American Aerospace Defense Command, the Department of Defense, or the US government.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.