Canoes dating back at least 8,000 years have been found from China to Nigeria and the Netherlands. Their history represents a global convergence of problem-solving and a unique story of place and culture. As a self-described river historian, I sometimes think of canoes as particular to rivers, but they have long been used along oceans, estuaries, rivers, and lakes and portaged across dry land. Canoes and their history can help teachers engage students by making connections across time and space that are grounded in the material world of flowing water or wooden boats.

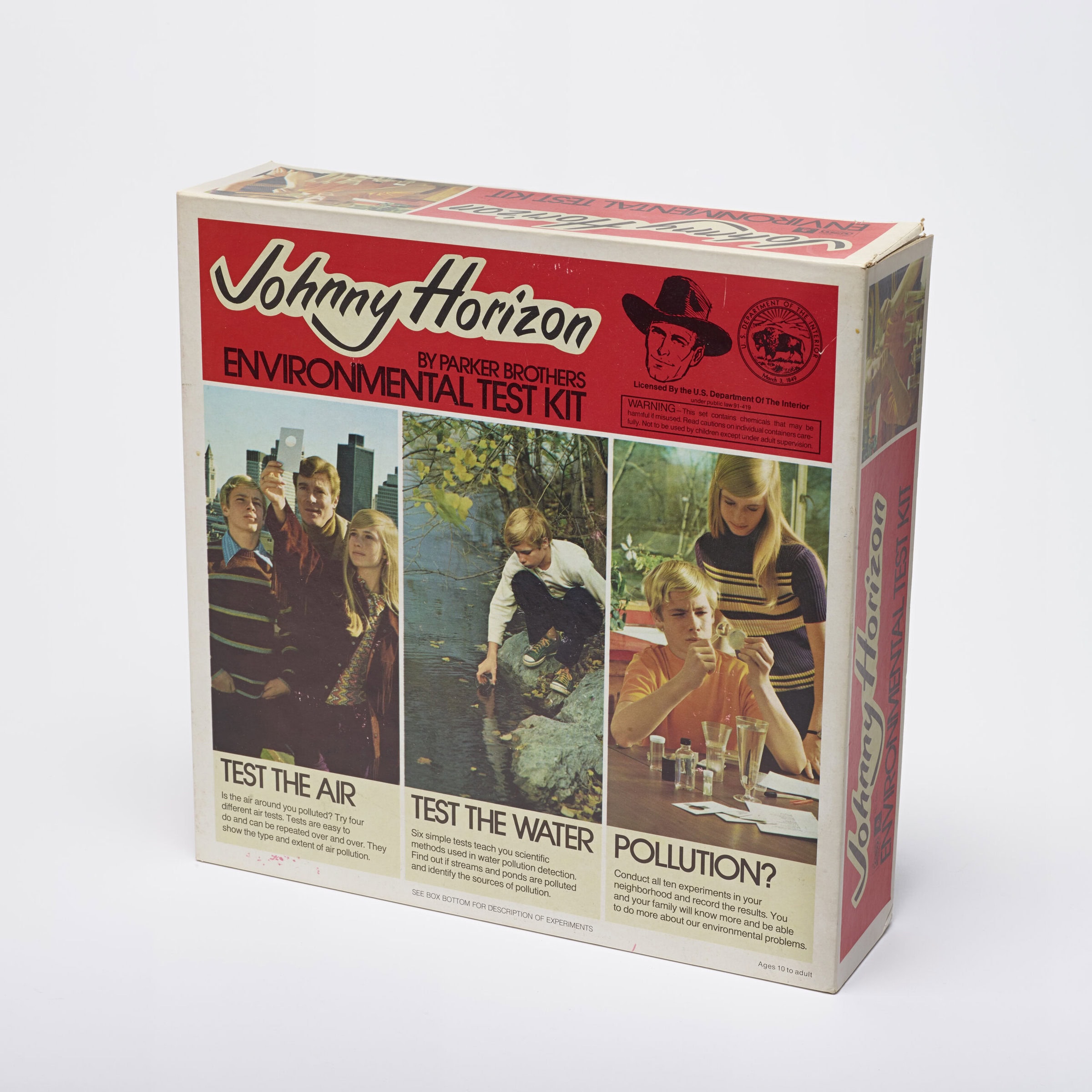

George Caleb Bingham, Fur Traders Descending the Missouri, Metropolitan Museum of Art, public domain

During the colonial period, the Wabanaki’s birchbark canoes empowered them as the dominant force on rivers in what is now Maine, limiting European settlement in the interior until much later than in places to the south. Birchbark canoes required large birch trees that did not grow in southern New England, where the majority of white settlers were located. Using a single peeled sheet of birchbark meant a canoe would have fewer seams that might leak. The canoes also used split cedar to strengthen them, spruce roots as thread to tie the bark to the frame and along its seams, and pine pitch or spruce gum to seal—all materials that came directly from the forest. European boats, in contrast, depended on wooden planks from mills or nails from a foundry. The birchbark canoe’s relatively narrow hull and paddle unattached to creaky oarlocks allowed the Wabanaki to stealthily attack British forces. When pursued, the Wabanaki could travel up smaller streams until the water turned to land, then carry their canoes into the next waterway. With their much heavier craft made from planks, exhausted Europeans usually gave up chase.

The birchbark canoe intersects with a key moment at the outbreak of the American Revolution. Before he became a famous traitor, Benedict Arnold led a daring mission to wrest control of Quebec from the British, with approximately one thousand Continental Army soldiers making a surprise attack from Maine. He planned to follow a Wabanaki portage route that linked the Kennebec River to the St. Lawrence River via smaller streams between. Hundreds of men died or deserted during this arduous journey. A portage route that could be traversed easily by Wabanaki people carrying 50-pound birchbark canoes was ill-advised with wooden boats weighing 400 pounds that rubbed soldiers’ shoulders raw.

The history of local waterways and canoe-like craft offers teachers an opportunity to connect students to local histories. Although few K–12 schools offer environmental history, many places, including Maine, mandate the teaching of Native history. Yet these mandates’ implementation has lagged because teachers often lack the resources to teach Native history and wish to learn more from historians. Canoes and the waterways navigated by Native people are one place to start. The global history of canoes is rooted in specific places, which can be useful even if you’re not Benedict Arnold trying to get to Quebec from Maine on a boat. In Maine, a common folk saying is “You can’t get there from here,” which is certainly true if you don’t know the history of canoes.

That history reverberates into the modern day. By the late 1800s, inspired by the birchbark canoe, several Maine-based canoe makers produced canvas canoes for recreational use. Many of the original employees of Maine’s Old Town Canoe Company, which eventually became the world’s largest and most influential canoe manufacturer, were Wabanaki Indians from the Penobscot Nation, whose reservation is just upstream on the river of the same name. Mass production has since replaced their handcraft, and today’s canoes are molded from plastic, not made from bark, wood, or canvas. Still, the next time you find yourself in a canoe, remember that its design is inspired by Wabanaki technology developed thousands of years ago.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.