Over the past few years, the humanities have been confronting a paradigm shift.

After the cultural and linguistic turns of the 1970s and 1980s, ideas about language, meaning, representation, power, agency, othering, and knowledge-production redefined the humanities. Now, in 2016, new media, climate change, environmental catastrophe, terrorism, biotechnology, population growth, and globalization are destabilizing the core of the humanities. These forces are larger-than-human—they are seismic and are shifting intellectual terrain. They also require a change of perception—a new, less anthropocentric, vision for a new century.

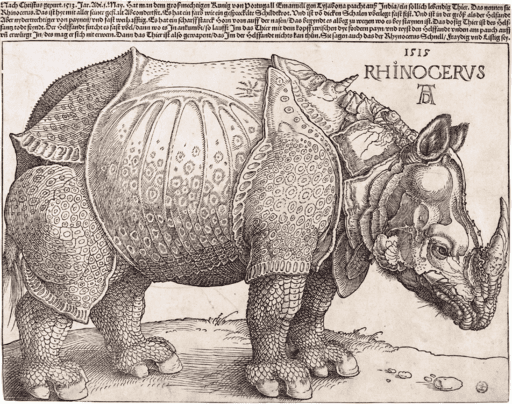

Dürer’s Rhinoceros. German painter Albrecht Dürer created this woodcut without ever seeing a rhinoceros.

As the macro, the “beyond-the-human,” quakes the ballast of the humanities, animals have emerged from the fault lines and fissures. Though animals were domesticated, commodified, and ultimately silenced between the late Paleolithic and the present, their voices have resounded across the humanities as it turns toward the Anthropocene.

Over the last 30 years, nonhuman animals have crept slowly, but persistently, from the margins of history to its center. As Harriet Ritvo put it in 2004, “animals have been edging toward the mainstream.” In the last decade, the pace of this animal migration has increased tenfold. The emergence of animals in the historical profession has not been the result of a single movement or particular subfield. Animals have found many gateways into our narratives.

Environmental history has shown that animals—along with plants, landscapes, earth systems, and ecosystems, among others—have been transformative agents throughout the entire breadth of human history. Intellectual history has demonstrated that thinking about and with the category “animal,” is to also think about politics, religion, society, and anything else that we humans have deemed important. Cultural histories have depicted animals as both important actors in and victims of human culture. Commodity histories have shown how animals are controlled, commodified, and shaped for human civilizations—for purposes of food, labor, clothing, entertainment, or materials. The histories of marginalization, examining race, class, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality, have detailed how the human constructs employed to otherize are almost always tied to ideas of “animals,” “species,” and “animality.” The history of science, technology, and medicine has examined how animals are both thought about and tested upon for purposes of knowledge and inquiry, as well as how animals are socially constructed. And world history, global history, “big history,” “deep history,” and “evolutionary history,” in trying to contextualize the human past within the largest of frameworks, have always looked at humans alongside animals, and indeed recently as animals themselves. Most of the historians who have introduced animals to history pre-date the rise of the newly articulated “animal history.” Nonetheless, the significant presence of whales and rodents, elephants and horses, bison and canines, squirrels, microbes, and other animals in contemporary historiography has produced an undeniable “animal turn.” And because animals have slithered into history from many directions, animal history represents a “turn,” not a specific subfield.

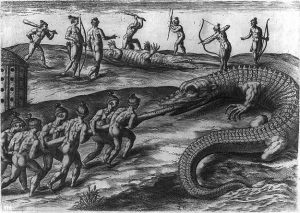

Jacques Le Moyne’s depiction of the Timucua encountering alligators in Florida. Engraving by Theodore DeBry. Library of Congress.

Animals have migrated into the historical profession from other disciplines as well. Over the last decade, animal studies, human-animal studies, critical animal studies, anthrozoology, as well as fields associated with the new environmental humanities, have been directing the historical profession in new directions. More importantly, animals have herded toward the historical profession from a growing global socio-political society desiring a sustainable future not plagued by overconsumption, exploitation, environmental destruction, and disregard for the rights of humans and other animals.

Animal history marks a growing constellation of historians turning toward animals to answer pressing questions about the past and present. Yet the challenge of animal history is great. In Susan Nance’s words, animal history calls on us to be “radically interdisciplinary.” Animal history challenges us to escape the deified anthropocentrism that has undergirded the pursuit of history, a task requiring understanding in philosophy and critical theory. Animal history challenges us to be conversant in the other disciplines of the humanities and to work with the sciences— ethology, ecology, animal welfare science, zoology, comparative psychology, veterinary medicine— to track animal agency in historical sources.

The standard narratives of civilizations, societies, and nations are built upon the backs of animals, large and small, even invisible. In many chapters of these tales, animals indeed prove more important than humans. It is time that we push through and past a human-centered historical tradition to uncover a livelier, more truthful, and complex past fashioned and experienced by all of the planet’s animals—human and otherwise.

Explore animal history at the 2017 annual meeting! Here is a glance at some of the sessions and papers of interest:

AHA Session 286

Incorporating the Beast: Traditional Historical Narratives and the Animal Turn

Sunday, January 8, 2017: 9:00 AM-10:30 AM

Centennial Ballroom F (Hyatt Regency Denver, Third Floor)

Chair: Aaron H. Skabelund, Brigham Young University

Papers:

Reading the History of Childhood in the Interwar Turkey through the Images of Animals

Melis Sulos, The Graduate Center of the City University of New York

Animal Welfare and Animal Rights Collections at NCSU Libraries/Special Collections and the Archival Landscape of Animal History

Gwynn Thayer, North Carolina State University Libraries

Preserving Animals, Establishing Identity: Taxidermy and Specimen Collection in the Pikes Peak Region, 1870–1930

Steve Ruskin, independent scholar

Supplantation, Memory, and the Veteran Status of War Animals since 1900

Chelsea Medlock, Oklahoma State University

AHA Session 42

Zoos and Global History

Thursday, January 5, 2017: 3:30 PM-5:00 PM

Centennial Ballroom H (Hyatt Regency Denver, Third Floor)

Chair: Nigel Rothfels, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee

Papers:

(Re)introducing Animals into Zoo History

Violette Pouillard, St. Antony’s College, University of Oxford

Penguin Parade and Flying Seals: “The Cult of the Cute” in Japan’s Northernmost Zoo

Takashi Ito, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies

Taxidermic Taxonomies: (Dis)Order and Deviance in the Zoo

Marianna Szczygielska, Central European University

The Zoonotic Nature of Tuberculosis

Daniel Vandersommers, McMaster University

Comment: Harriet Ritvo, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Climate Change, Herring, and Supernovae: How Environmental Changes Influenced Early Modern Empires

Dagomar Degroot, Georgetown University

Paper in New Directions in Environmental History, Part 1: The Environmental History of Early Modern Empires

Thursday, January 5, 2017: 3:30 PM-5:00 PM

Centennial Ballroom F (Hyatt Regency Denver)

Grains, Cows, and Canes: Integrated Agricultural Research as State Formation in 1930s Valle del Cauca, Colombia

Timothy Lorek, Yale University

Paper in Re-centering Crops in Latin American History

Friday, January 6, 2017: 10:30 AM-12:00 PM

Room 601 (Colorado Convention Center)

Vicuña Territory: Wildlife Management and State Conservation in Late 20th-Century Peru

Emily Wakild, Boise State University

Paper in The Environmental Management State in Latin America

Saturday, January 7, 2017: 10:30 AM-12:00 PM

Room 605 (Colorado Convention Center)

For a brief overview of animal history and its diverse approaches, here are a few “must reads”:

Virginia DeJohn Anderson, Creatures of Empire: How Domestic Animals Transformed Early America Etienne Benson, Wired Wilderness: Technologies of Tracking and the Making of Modern Wildlife Dorothee Brantz, ed., Beastly Natures: Animals, Humans, and the Study of History Richard W. Bulliet, Hunters, Herders, and Hamburgers: The Past and Future of Human-Animal Relationships Jon Coleman, Vicious: Wolves and Men in America

Brian Fagan, The Intimate Bond: How Animals Shaped Human History

Martha Few and Zeb Tortorici, eds., Centering Animals in Latin American History

Anne Norton Greene, Horses at Work: Harnessing Power in Industrial America

Donna Haraway, When Species Meet

Kathleen Kete, The Beast in the Boudoir: Petkeeping in Nineteenth-Century Paris

Alan Mikhail, The Animal in Ottoman Egypt

Susan Nance, ed., The Historical Animal

Karen Rader, Making Mice: Standardizing Animals for American Biomedical Research, 1900-1955

John F. Richards, The World Hunt: An Environmental History of the Commodification of Animals

Harriet Ritvo, The Animal Estate: The English and Other Creatures in the Victorian Age

Edmund Russell, Evolutionary History: Uniting History and Biology to Understand Life on Earth

Daniel Lord Smail, On Deep History and the Brain

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Dan Vandersommers is a postdoctoral fellow in animal history at McMaster University. He is coediting the volume Zoo Studies and a New Humanities with Tracy McDonald. He is finishing his own book titled The National Zoological Park and the Transformation of Humanism in Nineteenth-Century America. Also, his “Narrating Animal History from the Crags: A Turn-of-the-Century Tale about Mountain Sheep, Resistance, and a Nation” is forthcoming with the Journal of American Studies.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.