Have you ever done research in a library, museum, or historical society that had received funding from the federal government for preserving the records and artifacts in its custody? Did you ever use a digital finding aid that allowed you to locate the records? Or have you used documents in your classes that had been collected and edited with the support of the National Historical Publications and Records Commission? Have you enjoyed a Fulbright fellowship overseas or a term at a research center in the United Sates? Perhaps you have spoken at one of the hundreds of thousands of public programs sponsored by the state humanities councils over the last 30 or so years? Maybe you have found it extremely rewarding to work with K–12 history teachers over a summer with the support of a grant from the Teaching American History program? Or you work in a university or historical society, which has been able to endow a position or construct a building because of a development campaign leveraged by a National Endowment for the Humanities challenge grant. If your answer is “yes” to any of the above questions (and a host of others I do not have space to ask) your professional life has benefited from federal funding.

The American Historical Association, in coalition with dozens of other scholarly societies as well as higher education, library, archival, and museum associations, works hard to maintain a viable level of appropriations for the agencies and programs that support historical research and teaching. This is not a new effort. We have been encouraging the federal government to preserve national and local historical records for just about 125 years now. The number and variety of federal history programs have grown in the intervening years but so has the need.

Earlier this spring National Coalition for History Executive Director Lee White and I spent a few minutes totaling up the amount of federal funding that has an impact upon history. We have the Department of Education’s Teaching American History grants at $120 million for each of the last several years. The National Endowment for the Humanities received $144 million this year, much of which goes to historical projects. The National Archives, which relates to history in one way or another, currently has a total of $411 million, including $9.5 million for the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. The cultural programs of the National Park Service, including historic preservation as well as historical research and public programming at historic sites and parks, total $166 million this year, while the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History received $41.7 million. Within the Department of Education—which has a $2.1 billion allocation currently for higher education—the Javits fellowship program for doctoral students, much of which goes to future historians, is allocated $9.5 million, while foreign language and area studies programs receive about $109 million. The federal agencies and programs listed above total $891.2 million. Clearly, if we count other history programs in the Smithsonian, the various allocations for Fulbright fellowships, or the funds within the Institute for Museum and Library Services, the total for the history category will be well over a billion dollars—real money.

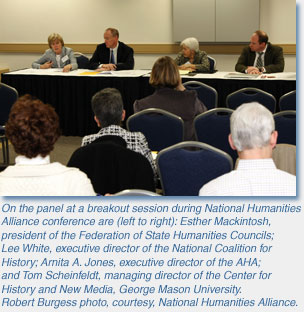

In early March, I, along with several staff and members of the American Historical Association, participated in Humanities Advocacy Day. A two-day effort convened by the National Humanities Alliance, it is preceded by a great deal of preparatory work and involves bringing together members of scholarly societies like the AHA as well as representatives of the museum and library communities, higher education associations, state humanities councils, and humanities centers on campuses. The first day began with a short business meeting followed by an opportunity to meet with representatives of federal funding agencies for an overview of their priorities and initiatives. The second day focused on Capitol Hill visits to make the case for appropriations on behalf of the federal agencies listed above that support the humanities. It is important work that the AHA fully supports, along with other efforts—particularly those sponsored by the National Coalition for History and the Consortium of Social Sciences Association—that focus on appropriations for the humanities.

In early March, I, along with several staff and members of the American Historical Association, participated in Humanities Advocacy Day. A two-day effort convened by the National Humanities Alliance, it is preceded by a great deal of preparatory work and involves bringing together members of scholarly societies like the AHA as well as representatives of the museum and library communities, higher education associations, state humanities councils, and humanities centers on campuses. The first day began with a short business meeting followed by an opportunity to meet with representatives of federal funding agencies for an overview of their priorities and initiatives. The second day focused on Capitol Hill visits to make the case for appropriations on behalf of the federal agencies listed above that support the humanities. It is important work that the AHA fully supports, along with other efforts—particularly those sponsored by the National Coalition for History and the Consortium of Social Sciences Association—that focus on appropriations for the humanities.

Our more time-consuming advocacy efforts, however, are not about money—important though it is. Historians particularly are affected by the often frustrating array of regulations and legislation that must be negotiated in order to pursue their research and, more recently, their teaching.

In the January 2008 issue of Perspectives on History AHA President Gabrielle Spiegel explored what she described as the mounting pressures to measure performance in undergraduate teaching and the need for historians to craft their own instruments of assessment before others were imposed upon them. Our annual meeting in January featured a special ad hoc session spotlighting the increasing problems foreign scholars are having in their efforts to obtain visas to attend conferences, pursue their research, or take up teaching positions, prompting AHA staff and officers to expand their efforts to provide advice and make inquiries on behalf of historians confronting such difficulties. Last fall we achieved an important victory in American Historical Association v. National Archives and Records Administration, the case dealing with an executive order relating to presidential records. Among the many other issues on which we have taken a public position are changes in copyright laws that threaten to impede scholars’ rights to publish their research, government classification procedures that unnecessarily restrict scholar’s access to records, and institutional review boards that often misunderstand the nature of oral history research. At the request of historians in Florida we weighed in on a new history curriculum in that state that aimed to replace “revisionist” with “genuine” history.

Doing all this work on behalf of the profession requires substantial effort and expertise from AHA staff and the volunteer efforts of many of our members and officers. We think it is important and we hope members do too.