“I’m not getting curry powder at all. Being a Brit, we eat a lot of curry, and I don’t taste it in this.” As I was watching Food Network’s Spring Baking Championship, this comment by Lorraine Pascale, one of the judges on the show, jumped out at me. Her comment, which drew on a legacy of presumed British culinary expertise concerning curry, carried a clear message: Brits know their curry.1 And yet, the process by which curry became one of the most popular dishes in modern Britain is a complicated one of imperial appropriation, invention, and transformation. In the same way that writing history is an act of interpretation, so too is the art of cooking an act of historical interpretation. Whether it’s preparing a family meal or competing on a national baking show, issues of assimilation and national identity are all up for contestation and negotiation in the culinary arena. Maybe Pascale’s comment, and the implied but unacknowledged history behind it, struck me because I’ve been thinking a lot about the culinary history of decolonization as we prepare the menu for the National History Center’s upcoming International Seminar on Decolonization Reunion Conference.

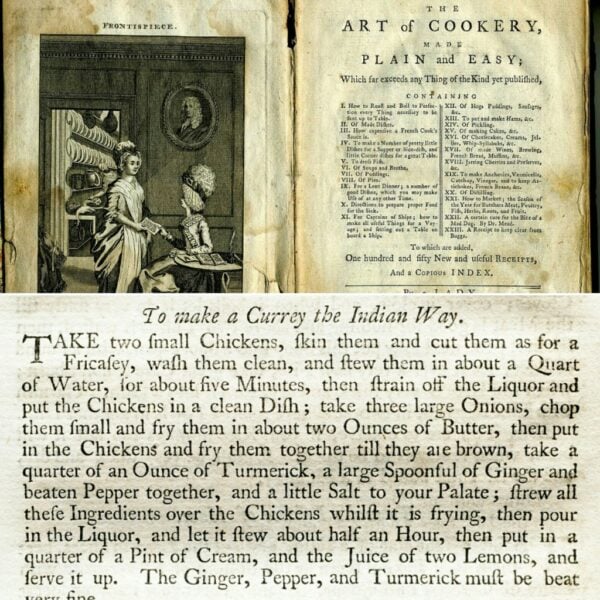

The first recipe for curry in Britain appeared in the 1747 edition of The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy by Hannah Glasse. Shown here are the frontispiece of the book and the text of the recipe. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Returning East India Company employees initially brought curry to Britain, but it was Anglo-Indian wives who played an important role in the transformation of curry dishes and their popularization at home. Memsahibs adapted local dishes to British tastes and needs, eventually codifying meals and homogenizing a varied cuisine under the blanket term “curries” through the dissemination of recipes at home. Some scholars have articulated this process whereby curry became a naturalized English dish as an act of incorporation, through which the colonial other was rendered less foreign.2 Similar processes occurred in France, where exotic colonial fruits, for example, replaced more traditional ingredients in French desserts, allowing for the inclusion of the exotic other without altering the traditional French forms.3

Culinary histories, however, are not only stories of assimilation and integration; food forms were also reified in order to protect and advantage imperial homelands while strengthening national symbols. In the case of wine production, for example, emphasis on the concept of terroir, along with the implementation of AOC laws (appellation d’origine contrôlée), protected the “Frenchness” of French wines from their colonial Algerian competitors.4 In this way, food history reveals both the imperial globalization of specific commodities, as well as the promotion of culinary symbols to strengthen national identity.

This process occurred not just in imperial homelands, but also in postcolonial states as they sought legitimacy after gaining independence. The codification of national cuisines for many African nations is complicated by their imperial legacies, differences in class practices, and the ways in which Western audiences shape the production of national cookbooks. Some nations, like Equatorial Guinea, have attempted to establish a national cuisine distinct from European influence (despite certain ingredients and dishes being eaten frequently), while others like Eritrea include Ethiopian and Italian influences as part of theirs.5 In the Middle East, cultural ownership of hummus has led Israel and Lebanon to create increasingly larger plates of the dish in order to hold the Guinness World Record. It is clear that the relationship between food, nation, and imperialism is part of the ongoing struggle of national identity for many states.

Given the reach of European and other earlier empires, as well as the impact of transnational migration on both sending and receiving nations, is an authentic cuisine even possible? If so, who owns it (if anyone)? Is it wrong for chefs to become famous for cooking another culture’s food? The online outrage at a Muslim woman winning the Great British Bake Off last year shows that national insecurities and food remain linked in the public imagination. Similarly, opposition to a Portland restaurant that seemed to celebrate the British Empire demonstrates that such culinary legacies are often emotionally fraught and contested. Examples like the above reveal how food forces us to engage with the history of empire and decolonization on a daily basis—as nations and individuals.

But what should that engagement look like? Can we, or should we, try to restore or create “authentic” cuisines? Or should we acknowledge the cuisines that emerged from colonial encounters as themselves authentic products of a region’s complicated past? Or does the embrace of hybrid cuisine make postcolonial nationalism impossible? The search for authenticity in food is in many ways similar to the search for historical truth: both inherently rest on context and interpretation. For many people, foods are the touchstone of national identity (e.g. as American as apple pie). The intensity surrounding food demonstrates how the personal is always political, and how the daily lives of so many people across the globe have been touched by empire and decolonization. In short, food clearly reveals the legacies of empire. It is these issues—and more—that the decolonization seminar has grappled with for the past 10 years; and we look forward to celebrating the intellectual contributions of all former seminarians as the series comes to a close this year.

Each summer since 2006, the National History Center has brought together a group of historians at the beginning of their careers to participate in the International Seminar on Decolonization. These seminars provided an opportunity for scholars to discuss, exchange ideas, and write about the phenomenon of decolonization, or the dissolution mainly of the European maritime empires in the 20th century. This summer, the National History Center will host a Reunion Conference that brings together seminar alumni from the past ten years in order to discuss and share their current work in the field.

Notes

- After fellow judge Duff Goldman commented that he could really taste the curry, Pascale responded, “I think she picked up turmeric or something. Because I saw some yellow, I smelled it, I tasted it, and I was just not getting any curry powder.” [↩]

- For more, see Troy Bickham, “Eating the Empire: Intersections of Food, Cookery and Imperialism in Eighteenth-Century Britain,” Past & Present (2008): 71–109; Eizabeth Buettner, “‘Going for an Indian’: South Asian Restaurants and the Limits of Multiculturalism in Britain,” Journal of Modern History 80, no. 4 (2008): 865–901; Nupur Chaudhuri, “Shawls, Jewelry, Curry, and Rice in Victorian Britain,” in Western Women and Imperialism: Complicity and Resistance, ed. Nupur Chaudhuri and Margaret Strobel (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992); Lizzie Collingham, Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors (Cambridge: Oxford University Press, 2007); Uma Narayan, “Eating Cultures: Incorporation, Identity and Indian Food,” Social Identities 1 (1995): 65; Cecilia Leong-Salobir, Food Culture in Colonial Asia: A Taste of Empire (London: Routledge, 2011); Mary Procida, “Feeding the Imperial Appetite: Imperial Knowledge and Anglo-Indian Domesticity,” Journal of Women’s History (2003): 123–48; Modhumita Roy, “Some Like It Hot: Class, Gender and Empire in the Making of Mulligatawny Soup,” Economic and Political Weekly 45, no. 32 (2010): 66–75; Susan Zlotnick, “Domesticating Imperialism: Curry and Cookbooks in Victorian England,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 16, no. 2/3 (1996): 51–68. [↩]

- Kolleen Guy, “Imperial Feedback: Food and the French Culinary Legacy of Empire,” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies 14, no. 2 (March 2010): 149–57. [↩]

- Kolleen Guy, When Champagne Became French (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003). [↩]

- For more, see Igor Cusack, “African Cuisines: Recipes for Nation-Building?” Journal of African Cultural Studies 13, no. 2 (2000). [↩]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

Related Articles

Sorry, we couldn't find any articles.