The Texas State Board of Education (SBOE) is no stranger to controversy. In 2016, Perspectives reported on the dispute over a Mexican American studies textbook submitted to the board for approval. And in September 2018, the SBOE once again made national headlines for its proposals to “streamline,” or to revise and review, the state’s social studies standards.

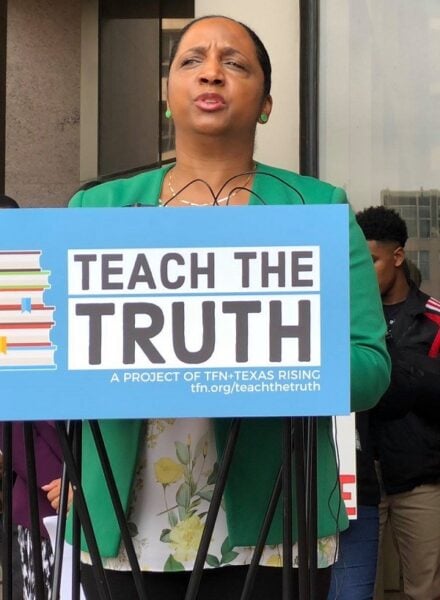

Daina Ramey Berry (Univ. of Texas at Austin) speaks at a press conference during an SBOE public hearing on changes to the social studies standards in September 2018. Texas Freedom Network

Outraged stories from liberal outlets emphasized the recommendations to remove Helen Keller and Hillary Clinton from the standards, to downplay the role of slavery as the central cause of the Civil War, and to leave in references to Moses as an individual “whose principles of laws and government institutions informed the American founding documents.” But indignation came from the right, too. Texas’s own Republican governor, Greg Abbott, reflecting conservative concerns about the proposed removal of the word “heroic” to describe the defenders of the Alamo, tweeted: “This politically correct nonsense is why I’ll always fight to honor the Alamo defenders’ sacrifice. . . . This is not debatable to me.”

What got lost in the headlines and the tweets, however, was why the SBOE was undertaking the streamlining process to begin with. A political body whose members are elected, usually along party lines, from 15 single-member districts across the state, the SBOE sets curriculum standards and reviews and adopts textbooks based on those standards for Texas public schools. While the cultural maelstrom focused on the ideological underpinnings of the proposed changes, the process itself was a product of one of the most difficult conversations that history educators tussle with: what should students learn when they study history?

The curriculum standards in Texas, also known as the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (TEKS), were first instituted in 1997, according to Dan Quinn, the communications director of the Texas Freedom Network, a nonpartisan organization that supports public education. Since then, the SBOE has undertaken several revisions of the standards, with the last major overhaul taking place in 2010.

On the surface, the process of revising the standards is relatively straightforward: the SBOE convenes curriculum teams, or “work groups,” comprising scholars, educators, and citizens from around the state to review the existing standards and suggest changes. The SBOE then holds public hearings on the recommended changes and later votes on them. The process is profoundly political, since board members are elected and Texas is a majority-Republican state; the SBOE is currently composed of 10 Republicans and 5 Democrats. Notably, few of them have any background in the field of education.

In 2010, says Quinn, once the local curriculum teams sent their draft changes to the standards up to the SBOE, “politics took over.” “Board members,” he recalls, “submitted hundreds of amendments to change the draft standards,” many of which were later adopted by the full board. According to a February 2018 report from the Texas Freedom Network Education Fund, authored by four scholars (including two historians), the 2010 amendments were based largely on the board members’ “own personal beliefs and pet causes,” many of which had no basis in existing scholarly consensus.

The cultural maelstrom focused on ideology, but the process itself came from a difficult conversation among history educators: what should students learn?

The resulting standards were so flawed that even the conservative Thomas B. Fordham Institute blasted them. The institute’s scorching 2011 review of state US history standards characterized the Texas standards as “a politicized distortion of history.” Among other things, noted the report, the standards offered an “uncritical celebration of ‘the free enterprise system and its benefits,’” completely overlooked Native Americans, downplayed slavery, barely mentioned the Black Codes or Jim Crow, and dismissed the separation of church and state as a constitutional principle.

But beyond politics, the 2010 process created problems for teachers in the classroom. The standards posed an instructional challenge because, says Quinn, they became “long and unwieldy.” Ron Francis, a seventh-grade social studies teacher at Highland Park Middle School in suburban Dallas, notes, for example, that because the standards are so long and are arranged chronologically, “teachers [often] have problems getting to the standards that are at the end of the course.” Additionally, Texas students are tested in the core subject areas of reading, writing, mathematics, science, and social studies, from third grade through high school graduation, as part of the state’s academic assessment program. (Texas does not participate in the national Common Core standards.) These standardized tests, according to Trinidad Gonzales, a historian at South Texas College and a past AHA Teaching Division councilor, “essentially just ask questions directly from the standards. If it says that you should know historical figures x, y, z, then the instructor . . . will basically teach x, y, and z. So what you have is a very test-driven, assessment-dictating curriculum.”

On paper, teachers do have the flexibility to teach content that is not included in the standards. “But the reality,” says Gonzales, “is that you’re trying to get the students to pass the exam.” And a passing score is required to move on to the next grade level or to graduate. Chances are, he says, “If it’s not in the TEKS, it’s not going to get taught.”

The goal of the 2018 streamlining process, then, was “to delete, combine, clarify and narrow the scope of the standards,” according to a June 2018 press release from the Texas Education Agency (TEA), which includes the SBOE. (The press release is no longer available online.) Streamlining would purportedly save class time and give teachers greater flexibility by eliminating or reducing what students could expect to see on the assessment test. Work groups were asked only to revise existing standards, not add new ones. And the SBOE did not seek updated textbooks.

The work groups’ imperative was to reduce instructional time, not impose a political point of view. Eliminating the World War II Women Airforce Service Pilots and the Navajo Code Talkers from the standards, the work groups estimated, would lead to a 30-minute reduction in instructional time; so would removing Billy Graham, Barry Goldwater, and Hillary Clinton. To consider which historical figures ought to be retained or eliminated, work groups drew up a rubric, awarding points based on an individual’s impact and sphere of influence, and whether the figure represented a diverse perspective or culture. Helen Keller, who scored 7 out of 20, was eliminated to save 40 minutes of instructional time. Misty Matthews, a teacher from Round Rock, Texas, who served on one of the work groups, told theDallas Morning News that “there were hundreds of people” students had to learn about. “Our task was to simplify. . . . We tried to make it as objective as possible.”

While state curriculum teams have attracted criticism in the past, experts believe that the 2018 work groups operated in good faith.

While TEA curriculum teams have attracted criticism in the past for having an ideological bent or for lacking expertise in curriculum development, both Quinn and Gonzales believe that the 2018 work groups operated in good faith. “In the streamlining process,” says Quinn, “we think the TEA did a really good job of making sure that these folks were actual educators—curriculum specialists who knew the field and how to teach. And frankly, . . . we saw really no problem with an effort to politicize the curriculum teams this time.”

But given the flaws of the 2010 standards, as well as some of the recommendations made by the work groups themselves, it was impossible for the 2018 streamlining process not to be interpreted politically. Many outside groups saw it as an opportunity to raise existing concerns about historical inaccuracies in the standards. Nearly 200 scholars, for example, signed a letter asking the SBOE to change standards that pertained to “issues of slavery, the Civil War, and the Civil Rights era.” Disability rights activists advocated that Hellen Keller be kept, and several local and national organizations protested what they perceived as a pro-Israel bias in the standards.

These types of recurring public controversies, write Lendol Calder and Tracy Steffes in “Measuring College Learning in History,” a 2016 white paper issued by the Social Science Research Council, “show that Americans continue to disagree” over the aims of history instruction, “especially the key goals, content, and narratives to teach in K–12 schools.” Increasingly, Calder and Steffes write, college-level instruction has shifted to emphasize “habits of mind of historical thinking.” But K–12 education measures learning as “students’ ability to remember and reproduce an authorized, unchanging canon of important facts and stories.” (The AHA’s History Discipline Core, meant to guide college curriculum, steers clear of outlining specific content that history students should know.)

What’s happening in Texas, says Gonzales, is a “classic content-versus-skills debate”—teachers would like more class time focusing on teaching such skills as historical thinking, but there is little consensus on how to assess them. Content knowledge, conversely, is easily measured and therefore remains in place, despite its many flaws. Most teachers inevitably find themselves teaching to the test. But as Calder and Steffes write, “The problem with including content knowledge as a goal for assessment is the question of which knowledge to test.” This is one reason why it has become impossible in Texas to separate politics from history education.

In November, after multiple public hearings and several amendments, the SBOE voted to streamline the standards. The revisions keep Keller, Clinton, and Moses, but continue to list sectionalism and states’ rights as contributing causes of the Civil War. Those seeking better accuracy or a trimmer set of standards will have to wait until the next round of revisions, which are still five years down the road. If things are to change, both Quinn and Gonzales say, more historians should get involved in the process of setting standards at the state level. Academics, says Gonzales, aren’t as involved in the process because often there’s nothing in it for them to gain professionally.

For now, instead of seeking a greater shift to skills from content in the Texas curriculum, activists, academics, and teachers in the state continue to focus on making the standards more accurate. “I think streamlining is a good idea,” says Francis, adding that “we need a better integration of content and process.” Yet in a “post-truth” era where “facts are possibly matters of opinion,” he says, the need for accuracy in content ought to take precedence.

Perspectives thanks Julia Brookins, AHA special projects coordinator, and Elizabeth Lehfeldt, vice president of the AHA’s Teaching Division, for their assistance with this story.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.