In Hollywood thrillers Islamic terrorists often replace the Soviet espionage agents of the Cold War era as cinematic villains. In the polarized post 9/11 political environment, however, neither Hollywood filmmakers nor American policymakers have paid much attention to the conditions that foster terrorism. The George W. Bush Administration’s answer to the rhetorical question “why do they hate us” was simply that terrorists were envious of American freedom and prosperity. In his University of Cairo address, President Barack Obama displayed greater sensibility to the concerns of the Muslim world. Nevertheless, the arguments offered by President Obama for escalating the war in Afghanistan appear to offer little hope for winning the hearts and minds of the Afghan people, not to mention their neighbors in Pakistan. Termed the graveyard of empires, Afghanistan is perceived by many in the Middle East as a target of Western imperialism. This legacy of imperialism is an issue which American filmmakers and politicians often ignore. Interestingly, though, many intriguing questions about the legacy of Western colonialism in the Middle East are engaged in an epic film of 1966, The Battle of Algiers, which was directed by Gillo Pontecorvo.

In Hollywood thrillers Islamic terrorists often replace the Soviet espionage agents of the Cold War era as cinematic villains. In the polarized post 9/11 political environment, however, neither Hollywood filmmakers nor American policymakers have paid much attention to the conditions that foster terrorism. The George W. Bush Administration’s answer to the rhetorical question “why do they hate us” was simply that terrorists were envious of American freedom and prosperity. In his University of Cairo address, President Barack Obama displayed greater sensibility to the concerns of the Muslim world. Nevertheless, the arguments offered by President Obama for escalating the war in Afghanistan appear to offer little hope for winning the hearts and minds of the Afghan people, not to mention their neighbors in Pakistan. Termed the graveyard of empires, Afghanistan is perceived by many in the Middle East as a target of Western imperialism. This legacy of imperialism is an issue which American filmmakers and politicians often ignore. Interestingly, though, many intriguing questions about the legacy of Western colonialism in the Middle East are engaged in an epic film of 1966, The Battle of Algiers, which was directed by Gillo Pontecorvo.

In this cinematic examination of the Algerian struggle for independence from French colonialism during the late 1950s and early 1960s, Pontecorvo exposes the ambiguous legacy of imperialism in Western efforts to combat indigenous resistance and terrorism. In light of the controversies regarding “extreme rendition” in undisclosed locations and American employment of torture in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Guantanamo Bay, considerable attention has been given to Pontecorvo’s message. The Italian filmmaker suggested that French counterinsurgency tactics such as torture may have won the Battle of Algiers but eventually led to the failure of the French to maintain their colony in Algeria. Thus, an August 2003 Battle of Algiers screening at the Pentagon was interpreted by the news media as raising questions regarding the efficacy of torture as a means for combating terrorism.

The Battle of Algiers is, however, much more than a film that is relevant to contemporary policies of the United States in Iraq and Afghanistan. It is also an important primary source in which an interpretation of the legacy of Western colonialism may serve as a stimulus for thinking about the roots of discontent with the West in the Islamic world. Consequently, The Battle of Algiers ought to find a place in the history curriculum of the schools and universities because of its usefulness to link the past and present and for telling a story of colonialism from the perspective of people that Frantz Fanon termed the wretched of the earth.1

Pontecorvo’s film is a product of the global anti-imperialist response in the 1960s which linked the struggles in Algeria, Vietnam, and Angola as well as in Latin America. Many alienated Western youth identified with this insurgency against capitalism and colonialism. Some joined radical organizations such as the Weather Underground in the United States, the Red Brigades in Italy, and the Red Army Faction in West Germany. A 1968 alliance between students and workers almost toppled the government in France, and that same year the “Prague Spring” in Czechoslovakia challenged the Soviet Union, an “empire” that many radicals perceived as even more reactionary than American “imperialism.” In the words of Bob Dylan, it did, indeed, seem the times were “a-changin.’”

With the gift of hindsight, it is easy today to dismiss the young people as naïve for hoping that world revolution could be achieved in the 1960s. Yet those who were caught up in the excitement of that era genuinely believed that radical change was possible.

Pontecorvo’s film about anti-imperialist resistance in the Algerian Revolution inspired some viewers with thoughts about challenging political authorities, an effect that created a good deal of controversy in the 1960s. Screenings for The Battle of Algiers were often perceived as fostering domestic insurrection and providing tactical instructions for revolutionaries. The film was initially banned in France, while in the United States the Algerian rebellion was equated with the black liberation struggle and the actions of the Black Panther Party. Bosley Crowther, the film reviewer of the New York Times, saw a connection with the protests of African Americans. “Essentially, the theme is one of valor,” wrote Crowther, “—the valor of people who fight for liberation from economic and political oppression. And this being so, one may sense a relation in what goes on in the picture to what has happened in the Negro ghettos of some of our American cities recently.”2

Pontecorvo and his screenwriter Franco Solinas wanted to portray the struggle of the National Liberation Front (FLN) to gain independence for Algeria and free the Algerian people from French oppression. Pontecorvo was a member of the Italian Communist Party who left the political organization following the 1956 Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Revolution. He sympathized with the Algerian revolutionaries.3 The director perceived the Algerian Revolution as part of a larger global anticolonial historical movement which he wanted to support with his filmmaking.

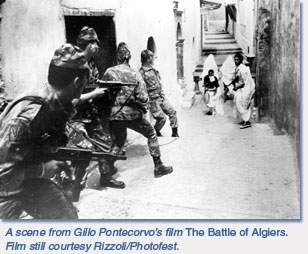

Pontecorvo filmed on location in the marketplaces and narrow streets of the Casbah, the traditional Muslim section of Algiers, employing nonprofessional actors. He wanted to create a sense of realism. Cinematographer Marcello Gatti shot the film in black and white, relying upon older film stock and handheld cameras to establish the look and feel of a documentary. This impression was enhanced by his use of proclamations broadcast on the radio by both the French and the FLN. The film looked so much like a documentary that American advertisements for The Battle of Algiers stressed that no newsreel footage was actually used in the production of the picture.

The goal of Pontecorvo and his Italian filmmaking crew was to present the FLN as freedom fighters that resorted to terrorist tactics as the only means available to combat the oppression of the French colonizers. To prepare the masses for struggle against the French, the FLN initiates a program of purification to rid the Casbah of drugs and prostitution, which the French have encouraged and tolerated. Following this purification campaign, the FLN then turns to the assassination of French policemen, the most visible target of French oppression in the daily lives of the Algerian people. At this point in the film, Pontecorvo is careful to suggest that the revolutionary violence is not directed toward French civilians. It is the French who raise the stakes by placing a bomb in the Casbah, indiscriminately striking at Algerian families while they sleep. In response to this atrocity, the FLN provides three Muslim women with basket bombs. Dressed in European fashion, the women place their bombs in the offices of Air France, a cafe, and an ice cream bar frequented by young people. In depicting the death and destruction wrought by the bombings, Pontecorvo appears to be defending the necessity of such terrorist tactics without glamorizing them.

In reaction to the bombings, the French government dispatches paratroopers under the command of Colonel Mathieu to Algiers. After crushing a general strike called by the FLN, Mathieu wages a campaign of torture until the FLN leadership in Algiers is destroyed. A confident Mathieu declares victory in the Battle of Algiers, which is over in 1957.

But this is a Pyrrhic victory, for in the film’s epilogue the masses of Algeria arise in 1960, beginning a violent struggle which culminates two years later in Algerian independence. The film’s conclusion seems to suggest that the FLN served as a Marxist-Leninist vanguard of the proletariat by raising the consciousness of the Algerian masses. The Battle of Algiers also explores the roots of anti-colonial violence in imperial exploitation and suppression while exposing the shortcomings of torture and repression in dealing with the aspirations of colonized populations.

Although The Battle of Algiers omits several historical details by focusing only upon FLN opposition to the French and ignores problems associated with governing Algeria after independence, I have found the film to be a valuable teaching tool in my college preparatory classes. The Battle of Algiers provides a useful vehicle for the discussion of colonialism, wars of national liberation, and leftist politics, as well as contemporary issues regarding terrorism, torture, and the American military interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan. While Pontecorvo clearly perceived his film as supporting the cause of the revolutionary FLN, it is interesting to note that many young people view The Battle of Algiers as more even-handed, deploring the terrorist tactics of both the French and FLN. Students recognize the valid aspirations of colonized people, but they want to find a path toward a more just world short of romanticizing violent revolution. The message which enticed many young people in the 1960s gets a different reception in our time.

Notes

Ron Briley teaches history at the Sandia Preparatory School in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He is also assistant head of the school. A recipient of the Beveridge Family Teaching Prize from the AHA, he has several publications on film, politics, and sports. He is currently a member of the AHA’s Committee on the John E. O’Connor Film Award.