In the summer of 2013, I had the incredible fortune to participate in the National History Center’s 8th International Seminar on Decolonization in Washington, DC. I had just received my PhD in history and French studies at New York University and was about to start a postdoc at Tulane University. Although much of the seminar focused on helping participants advance their own research projects on the history of decolonization, I found that some of the most engaging conversations I had with both the seminar faculty and with my fellow participants centered on teaching.

As a recent PhD about to start my first teaching job, I knew little about how to design a syllabus, how to teach students to use primary sources, or how to incorporate multidisciplinary pedagogical approaches into the classroom. During my year of teaching at Tulane, I designed a senior capstone seminar for the history department (which I now teach as an international studies capstone at the University of Oklahoma) that incorporated ideas I’d gathered from the many discussions on teaching during the seminar.

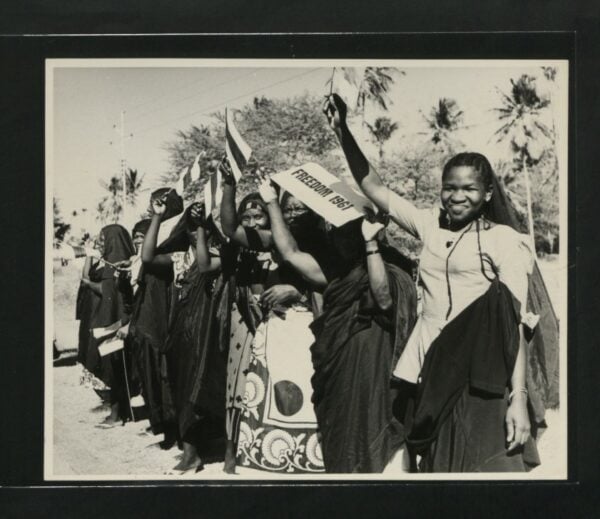

This course, entitled “Decolonization: The End of Empire in the Twentieth Century,” explores the process of decolonization from multiple viewpoints, and attempts to situate the unraveling of European empires in a broader global context. The course begins with an exploration of the different challenges to the colonial project coming both from inside and outside European empires. We then trace the process of decolonization in different areas of the world: Southeast Asia, the Caribbean, and Africa. Through an examination of the Algerian war, for example, we consider the role of violence in the decolonization process. We read Senegalese author Ousmane Sembène’s novel, God’s Bits of Wood, and explore both the role that labor played in decolonization and the way that African authors contributed to the imagining of an independent Africa. We then consider the role that both the United States and international organizations played in facilitating the end of European empires through a reading of Aiyaz Husain’s Mapping the End of Empire: American and British Strategic Visions in the Postwar World (2014) and Mark Mazower’s No Enchanted Palace: The End of Empire and the Ideological Origins of the United Nations (2009). We read these alongside reports from the UN Special Committee on Non-Self-Governing Territories. Over the course of the class, students develop their own research projects and collaborate with their classmates to refine their research and writing skills.

Despite having taught the course twice, I was eager to explore ways to reframe and rework its design. In an effort to continue the conversations about teaching that had begun at the Decolonization Seminar, I organized a roundtable for this year’s annual meeting of the Society for French Historical Studies, which convened in Nashville during the first weekend in March. My contribution to the roundtable focused on building a class archive of primary sources related to the end of empire, which I find to be especially crucial when teaching somewhere without access to a major research library. I encourage students to make use of online resources like the Foreign Relations of the United States series (FRUS), British Documents on the End of Empire, and the British Colonial Film Archive. I also direct them toward excellent edited collections of primary sources, such as Todd Shepard’s Voices of Decolonization: A Brief History with Documents (2014). Elizabeth Foster (Tufts Univ.), also on the roundtable, focused on the problem of encouraging students to consider the role of non-state actors—such as the Catholic Church—in the decolonization process. Melissa Byrnes (Southwestern Univ.) and Larissa Kopytoff (New York Univ.) considered ways to incorporate decolonization into more general survey courses and in courses on topics like race and immigration in Europe. Questions raised during the discussion with the audience prompted us to reconsider how we incorporate other sources like films and novels into our classes, and how to deal with the problem of translating sources from French.

While I took away many specific ideas for new assignments, new films, and even new classes from the panel, what struck me the most was how excited my co-panelists and the audience were to have a forum to discuss teaching. While most of our graduate education in history today focuses on training us to be good researchers and writers, we spend significantly less time training graduate students to be good teachers. Although many of us go on to work in institutions where teaching comprises half—if not more—of our workload, most of us finish our PhDs with very little experience designing assignments, building reading lists, or formulating a class syllabus. My colleagues and I left the roundtable feeling both energized and optimistic about future possibilities for conversing about and collaborating on teaching. I look forward to continuing these discussions at the next meeting of the AHA in January!

is assistant professor at the University of Oklahoma, where she teaches courses on global decolonization, public health in Africa, and race and immigration in Europe. Her research explores the intersection of internationalism and empire after 1945 through the lens of public health in French sub-Saharan Africa.

Each summer since 2006, the National History Center has brought together a group of historians at the beginning of their careers to participate in the International Seminar on Decolonization. These seminars provided an opportunity for scholars to discuss, exchange ideas, and write about the phenomenon of decolonization, or the dissolution mainly of the European maritime empires in the 20th century. This summer, the National History Center will host a Reunion Conferencethat brings together seminar alumni from the past ten years in order to discuss and share their current work in the field.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.