Student interest in the Middle East and its history in North American universities has proliferated notably in response to the recent global-scale conflicts directly or indirectly related to the region and the Muslim world. The single most important turning point was of course the September 11 attacks. However, more recently, the popular surge for democracy in the Middle East, i.e. the Arab Spring, has further propelled student interest. While this soaring interest provides teachers of Middle Eastern history with an opportunity to tackle the problem of prejudices and stereotypes traditionally associated with the region and its peoples, the fact that the very same prejudices and stereotypes lie behind the intellectual curiosity of our students poses a major field-specific challenge.

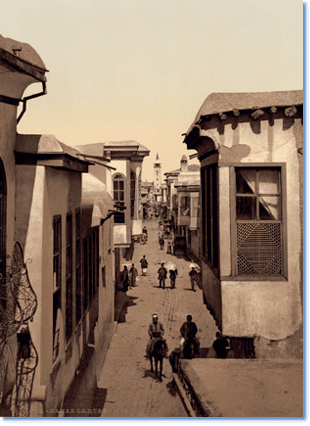

The street called straight, Damascus, Syria, between ca. 1890 and ca. 1900. From the Views of the Holy Land Photochrom print collection, Detroit Photographic Company. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LOT 13424, no. 030

For the majority of undergraduate students, the notion of the Middle East evokes terrorism, armed conflicts, bearded men, veiled women, and anti-Western dictators. Such stereotypical portrayals of the Middle East arise from the fact that the region is imagined to be a static one with a monolithic and religiously oriented culture. When asked what they wanted to learn about the Middle East, several of my students responded by saying that they wanted to know why Middle Easterners were bent on destroying the West.

The main task for a teacher, therefore, is to figure out how to stimulate students’ intellectual curiosity while fostering critical perspectives to help them reach an understanding of the Middle East as a part of global history, and free from the aforementioned prejudices. For this reason, I prepare each of my lectures woven around the idea that far from being stagnant and monolith, as it is frequently depicted in the Western media, the Middle East is a diverse region with numerous languages, ethnicities, religions, and cultures and that the region has transformed itself multiple times in line with global connections. The first premise is straightforward and easy to incorporate into lectures. For example, a lecture on the Crusades does not have to focus solely on religious conflict and warfare. One can talk extensively on how individual Muslims and Crusaders of various ethnic and sectarian backgrounds interacted in their daily lives and learned from each other, thanks to the available primary and secondary sources in English, which, in my experience, was more appealing to the students.

The second premise requires us to show our students how the local is connected to the global. In order to achieve this, one ought to place the Middle East within a global history to which we all belong by pointing out how the region responded to global trends such as the commercial and industrial revolutions, nationalism, imperialism, colonialism, and advancement of technology. Some global trends such as oil dependency are familiar to students. Taking this into account, a teacher can elucidate the response of the Middle East to the global dependency on fossil fuels and its transformations since it became the largest exporter of this commodity. Similarly, while explaining the Arab Spring, one can discuss advancement of technology and communication as another global trend that is currently re-shaping the post-WWII political structures in the Middle East by focusing on how the Internet and social media have became inevitable tools for Middle Eastern peoples to organize their struggle to reform or overthrow oppressive regimes in their countries. Picturing a protesting Egyptian in Cairo’s Tahrir Square tweeting on her/his smart phone to inform the rest of the world is a very convincing image for our students to understand that global connections exist in every part of the world.

Another very productive strategy in engaging the aforementioned main problem is to take advantage of the fact that religious or political conflicts in the region often become the headlines in the North American media by using them as teachable moments. To illustrate, I noticed that while my students showed marginal interest when I talked about the millet system in the Ottoman Empire, they were more enthusiastic to learn about it as soon as I guided them to make the connection between some current ethnic-religious conflicts in the region and the Ottoman millet system.

The millet system was devised by Ottoman rulers to ensure the division and integration of various confessional communities into the state by granting them the right to administer their own religious and judicial affairs. Based on the idea of social boundaries between religious groups, the millet system enabled the Ottomans to regulate transactions between their subject populations. The legal division of confessional communities was inevitably reflected in the settlement patterns in Ottoman cities. Cities had their Christian, Muslim, and Jewish quarters. This pattern of settlement has continued in the modern Middle East.

When I explained how the millet system and the consequential Ottoman demographic and social policies were influential in certain conflicts between confessional communities in the Middle East, students began to ask more questions about the millet system and the Ottomans in an attempt to understand the subject better. Such teachable moments not only provide us with means of establishing connections between the past and the present, but also enable us to challenge certain prejudices. In this specific example, students learned how an Islamic empire promoted religious tolerance and allowed many different cultures and languages to flourish under its rule, contrary to the widespread notion of Muslims being extremely intolerant of others.

In addition, using visual media to introduce the realities of the Middle East, I have observed that a dramatic foreign film from the Middle East about life in a certain part of the region yields more fruitful results than a documentary. Besides being less dreary, a dramatic film gives students the chance to observe the life in the region from a Middle Eastern perspective. Students can also perceive that an average person living in the Middle East is coping with the same everyday problems as those in the United States or in Canada. Many Middle Eastern movies that deal with everyday life or broader challenges of living there are easily available in North America. To illustrate, I recently showed my students an Israeli movie entitled Ajami, which explores the lives of several families belonging to different ethnic and religious groups in the Ajami district of Jaffa. Besides touching upon the broader Arab-Israeli relations, this movie focuses on everyday problems of individuals. After watching the movie, several students came and told me how misunderstood they thought the region and people were. Moreover, students referred to the movie in class discussions when we talked about the prejudices associated with the region.

This sort of approach to teaching Middle Eastern history has helped me foster a less biased understanding of the Middle East, especially in those students who wanted to know why Middle Easterners were bent on destroying the West or who thought that all Middle Easterners were turban-wearing, camel-riding Arabs. I have even had students who decided to travel or teach English in the Middle East after they realized how complex and diverse the region was.

Courses on Middle Eastern history are pivotal in empowering our students with an unprejudiced perception of one of the most misunderstood regions of the world. Through our dedication, our students can grow to become informed citizens questioning what they read or see in the media rather than blindly accepting everything as facts. Anybody can learn what the Mandate System was and how it worked in Middle Eastern history by reading a textbook or an encyclopedia entry. However, without the assistance and guidance of dedicated professors and supportive institutions, very few will be able to analyze and reflect on how the Mandate System and its outcomes have shaped and are still affecting the Modern Middle East. Those students who can may even work to find real and applicable solutions to current problems in the region.

The last decade has seen great strides and productive scholarly output in the field of Middle Eastern history. This trend is likely to continue as the recent headlines have shown us that North American policies on and attitudes towards the Middle East are changing every day. Therefore, while history departments and universities should place more value on Middle Eastern studies, professors must nurture students willing to pursue careers pertaining to the region for the contributions that the field has the potential to engender.

Murat Yaşar is an assistant professor at the State University of New York at Oswego. He has taught courses on Middle Eastern history at the University of Toronto, Trent University, and the University of Western Ontario.