A historian colleague once remarked, as he looked through a flier announcing a critical thinking conference, that he had a sense of what critical thinking was, but he thought it was something we, as historians, already did. It is true, historians are critical thinkers, but the discipline of history is often misunderstood as being too concerned with content over process (in much the same way as critical thinking is sometimes misrepresented as stressing process over knowledge). Historical methodology is, indeed, critical thinking methodology, and the two disciplines are mutually beneficial.

This paper is addressed to teaching historians in general, and specifically to those who have answered the call to teach critical thinking skills, whether as a result of recent state mandates or the particular needs of different institutions. I hope to suggest a few guidelines for teaching critical thinking skills and to encourage other historians to consider teaching a rewarding class. The good news, I think. is that we historians are particularly adept and qualified to teach such skills. The bad news is that we have a multitude of tasks ahead of us.

The first of these is one that most of us are familiar with: the need to help students overcome what Robert F. Berkhofer, Jr., defined in Perspectives (February 1988) as their “historical fundamentalism”-the belief that readings and textbooks are divinely inspired and that history is a collection of facts to be learned. Second, when students have learned that all historians do not interpret the past uniformly, that historians ask different questions and uncover different answers, the teacher of critical thinking has to steer students away from the twin anticritical traps of relativism (i.e., there is either no meaning or nothing to be learned from history because it all depends on a relative point of view) and cynicism (i.e., history is a tool of those in control and thus nothing can be learned from it). Third, historians must both consciously use and teach the skills of a critical thinker (which I would argue are inherent in the discipline of history). Finally, historians must contribute to or facilitate students’ growing knowledge about the nature of history and their place in it.

(Although historians need not be familiar with the pedagogical debates within the field of critical thinking in order to teach effectively a critical thinking class, those interested in recent research and useful bibliographies can consult infusing Critical Thinking into College and University Instruction [The Center for Critical Thinking and Moral Critique, Sonoma State University, Rohnert Park, CA 94928, n.d.] or Richard W. Paul, Critical Thinking: What Every Person Needs to Survive in a Rapidly Changing World [Rohnert Park,1990].)

Despite differences in emphasis, scholars of critical thinking collectively stress several elements: skills that can be taught (just as one can teach historical methodology—the whats, whys, causes, consequences, and relevance of history and society); a self-consciousness about the process (i.e., it is the rare historian who does not acknowledge, or at least make implicit, point of view, bias, or theoretical perspective—and surely no thinking historian today would suggest that history speaks for itself); a reliance on rationality (i.e., the key to historical argument is the evidence); and a goal (i.e., the questions directed at the past express concerns of the present).

I am taking it for granted that most readers of this column are familiar with the methodology of history: the detective work of searching out clues for a meaning of the past, self-consciously shaping our historical questions, selecting and interpreting the evidence, keeping our eyes out for anomalies, trying to make sense of our data, organizing and writing the narrative of our results, contributing to human knowledge, and discovering meaning or even answers in the past to our concerns of the present. And I’m also assuming that, despite our interests and training, much of our time as historians is spent in the didactic imparting of information (hoping that a challenging paper or research topic will stimulate thought). Even in a Socratic-style seminar much of our energy goes to facilitating student reading and helping with background information. The stuff of history is fundamental. I’m not making an argument for process over content, but historians, at least in American colleges, have the double duty first to erase from students’ minds that history is just something in the past and removed from their lives, and second, not only to explain how our students are related to the past, but to help them understand and know the past they are related to. Finally, my third assumption is that most historians who have pursued advanced degrees have done so because of interest: i.e. there is something about the discipline that appeals to us.

With these points in mind, I urge all historians to teach a critical thinking course on occasion. I suggest we follow our own interests and lead our students to a path of discovery and intellectual adventure. Unencumbered by the need to “cover” certain material, the historian-cum-critical- thinking teacher can share with students both the excitement of historical research and the recognition that we are all a product and a part of history. And, of course, this self-conscious identity as being part of a greater whole—past, present, and future—not exempt from the forces of history and responsible for shaping the future, is an ideal the critical thinker and the critical historian share.

My experiences teaching critical thinking may reinforce my contentions. Briefly, I divide a course into three sections. The first is devoted to a study of historical methodology; the second applies this methodology to an understanding of historical topics; and the last applies this methodology to concerns and issues of everyday life.

Any basic methodology source or text should work for the first part, but I use James West Davidson and Mark Hamilton Lytle’s After the Fact: The Art of Historical Detection (2nd ed., New York, 1986) because its essays are lively, the topics are broad, and students have found it provocative. Students soon learn that historians are not couriers between the past and the present; they are, instead, scholars who use a variety of skills and techniques to uncover, analyze, interpret and evaluate the past. The first essay, for example, discusses the strange death of Silas Deane, a midlevel American diplomat of the Revolutionary period. What his contemporaries, including Jefferson and Adams, believed to have been his suicide, looks to modern eyes like possible murder. Historians, recognizing anomalies in the official account of Deane’s death, having asked new questions regarding his motive for suicide, expanded the context of the investigation, which then led to evidence of spying and counterspying, code words, secrets, blackmail, and poison. Thus, two questions a good critical thinker asks are, what do we know and what could we know? The death of Silas Deane is a good introduction to evidence and knowledge.

Another essay, “View from the Bottom Rail,” investigates the lives of slaves and newly-freed slaves in the American South. How can we in the late twentieth century understand the conditions of the newly free over a hundred years ago? Quickly we realize that accounts of slavery by plantation owners, union soldiers, abolitionists, and Northerners are colored tremendously by both ignorance and point of view. Few slaves left written records. Few were literate. Yet we are in luck, because part of the legacy of the New Deal of the 1930s was an extensive collection of oral histories of former slaves. Taking into account that these people were elderly and that their perceptions and memories of slavery were from childhood, here, at least from the words of the freed people themselves, should be truth—some hard facts at last. Needless to say, such facts should not stand alone.

Upon further searching, the authors uncovered two fascinating interviews with the same woman—one concentrating on the tough times of slavery, but cushioned by a basically benevolent master; the other detailing horrors and inhumanity perpetuated by whites against blacks. The difference between the seemingly contradictory accounts lay with the interviewer. The former slave believed one of her interviewers (a white woman) to be a social worker with a welfare check. Her dependence on that check was possibly a factor in her qualified reminiscences. The other interviewer was, by inference, a black man with whom the freed woman may more readily have shared her fear of whites. This essay shows how interpretation, point of view, and bias affect our understanding of facts. Questioning the facts is a crucial critical thinking technique. The view from the bottom rail was the slaves’ point of view. Much history, much analysis, and even most modern newscasts are top rail. Critical thinking skills recognize the existence of both and the relative value of each.

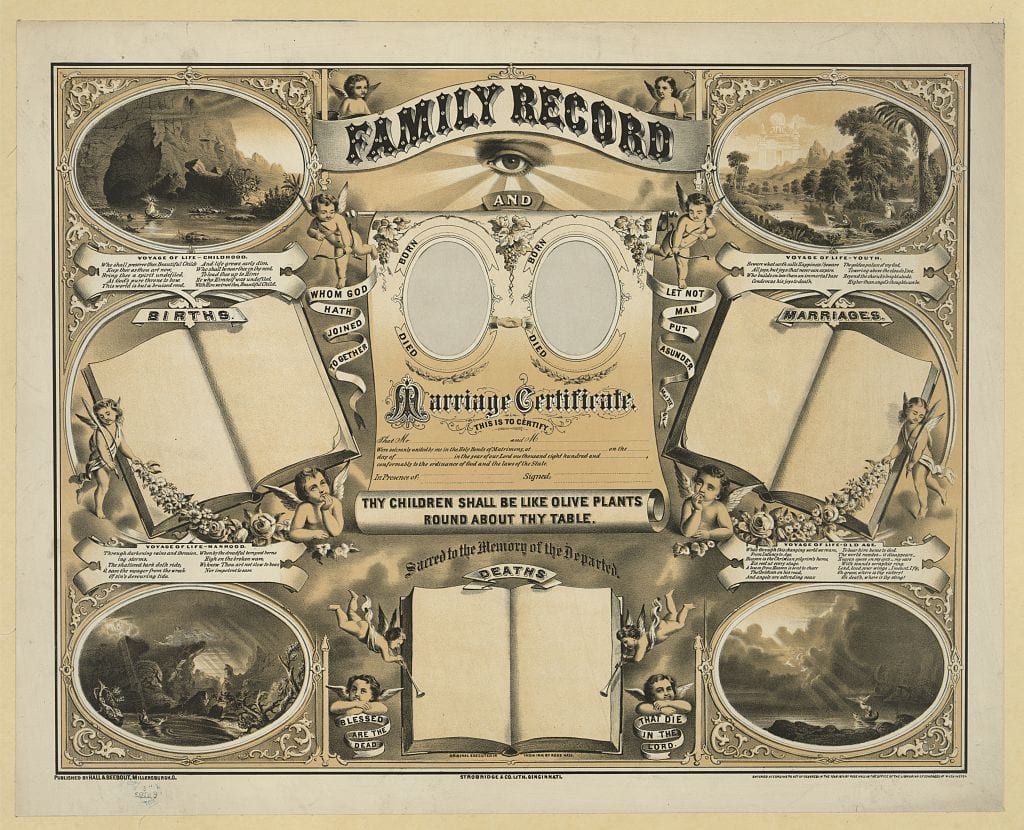

Another essay, “Mirror with a Memory,” discusses Jacob Riis’ groundbreaking expose, How the Other Half Lives. This work documented the urban poverty and living conditions of early twentieth-century American immigrants with the use of the fairly new technique of photography. Here students come to terms with technology and persuasion, with issues of motive, selection, visual interpretation, aesthetics versus statement, etc. Thus, one can be moved by a picture of a street lad sleeping in a New York gutter in 1915, even when investigation reveals that the picture was posed: the motive was good. What about the pictures on television today? What are they showing? What isn’t being shown? If one picture can move, can too many numb?

Davidson and Lytle also reveal Riis’s bias in favor of Northern Europeans and his negative stereotyping of Bohemians and Jews. The authors consider these factors in their evaluation of Riis’s purpose and success in awakening the public to the tragedy of the slums.

Another essay in the collection, “From Rosie to Lucy,” extends the Riis analysis to a study of television in the 1950s. The images on television in the 1950s (and since then, for that matter) are theoretically less didactic and polemical, but the same techniques that go beyond content analysis, such as interpreting placement of images, evaluating corroborative evidence, questioning the production as well as the product (Riis as well as his pictures; the networks as well as “I Love Lucy”), and determining what is being shown as well as what is being seen (two very different things, because the latter must deal with interpretation from different points of view) can be addressed and, consequently, can help us understand our own popular culture. Few minorities or women who worked for pay were represented in the first twenty years or so of television. What does this say about working women and minorities in those years? Since comparison is a crucial component of historical methodology, what can we learn by comparing, for example, 1960 with 1990 on the basis of television images?

Other essays deal with, among other things, inference, contradictory data, and value-laden interpretations. By the end of the first third of the course, then, most students are asking good questions and, more important for critical thinking, they are not expecting the instructor to answer them. They are, instead, becoming their own detectives. We can help them with research skills, but the quest for knowledge is theirs.

The second third of the course concentrates on applying these newly found historical skills and methods to the (allegedly) real substance of history: to either the documents, laws, and written words of history, or to what I call the ”utions” and “isms” of history (i.e., “utions” are, of course, among other things, revolutions, evolutions, and solutions; “isms” include imperialism, Marxism, capitalism, romanticism, and feminism). On alternate semesters we have focused on either the American Declaration of Independence or German fascism.

Thus, for example, now armed with an understanding of historical methodology, the class looks at two important historical studies of the Declaration of Independence. We compare Carl L. Becker’s The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of a Political Idea (New York: 1952) with Garry L. Wills’ Inventing America: Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence (New York: 1979). One thing that immediately surprises many students is that both Wills and Becker study the primary author of the Declaration of Independence in order to understand the text. Thus, a study of the Declaration is really, in large measure, a study of Jefferson. But although both historians attempt to understand the world of Thomas Jefferson, they define it differently. Carl Becker situates Jefferson’s world in the realm of ideas and, in particular, a Lockean concept of natural rights. Garry Wills, on the other hand, finds the eighteenth-century Scottish philosophers to be more significant in shaping Jefferson’s world view.

Students soon recognize that while Becker concentrates his analysis in the lofty realm of ideas (a variation on the “top rail” point of view), Wills attempts to understand what the words of the Declaration meant to the eighteenth century person. Wills argues quite persuasively, for example, that “pursuit of happiness” was a scientific concept; pursuit, in the science-conscious times of the Enlightenment, meant an almost gravitational pull, and happiness was believed to be quantifiable.

Finally, the assignment for this segment of the course asks students to use their critical thinking and historical methodological tools to do to Becker and Wills what Becker and Wills did to the Declaration. With a careful and critical reading of the two books, most students also learn about Becker’s disillusionment with World War I and his fear of rising authoritarianism in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s. They also discern Wills’s opposition to America’s intervention in Vietnam in the 1960s. They see a historical interchange between past and present and, through this study of a historical document, they learn a lot about the causes and consequences of wars and revolutions (whose applicability to modem life may be, unfortunately, all too relevant).

As an alternative to the segment on the Declaration of Independence, my class has focused on the rise of European fascism. Here we investigate German Nazism, but instead of comparing two written studies, we look at a book, a motion picture. and a documentary. William Sheridan Allen’s The Nazi Seizure of Power(New York: 1984) utilizes voting records, contemporary newspaper articles, employment information, and other evidence to trace the rise of Nazis to a small German town. We contrast this historical study with Just a Gigolo, a 1979 motion picture that fictionalizes many of the concepts and events the more scholarly studies of Germany in the 1920s analyze, such as the concept of “stab in the back,” the tremendous inflation, and the spread of Nazism, literally beneath the streets of Berlin. The use of the motion picture helps students understand that these historical methodologies, these critical thinking techniques, can be applied to their own milieu of popular culture. (The film stars David Bowie, Marlene Dietrich, and Kim Novak.) For heuristic and ethical purposes, we also view one episode of the 1985 documentary Shoah. Here we can apply critical analysis to both the topic of Nazism and to the vehicle of information, the documentary; but because Shoah treats so vividly the consequences of Nazism in the Holocaust, it adds another dimension to our study of how critical thinking is crucial to our lives: i.e., there are both causes and consequences of actions in history, just as there are in daily life.

The assignment for this segment of the course asks students to evaluate their own understanding of Nazism as they acquired it through these different sources of information. They soon realize that they absorb information from popular culture as well as from books and documentaries. Most recognize the need to ask critical questions of all three.

Historians as critical thinking instructors can choose any books or approaches to their fields that treat an issue differently. It is not really the definitive interpretation that is sought but the process of getting there. What is exciting about teaching critical thinking is that we can teach our field and share with our students our enthusiasm for it. Interestingly, because by the second third of the course the students are now armed with an understanding of methodology, the different interpretations, far from confusing them, typically add to their knowledge of the subject in question and give them an appreciation of the tasks necessary to get that knowledge.

The last part of the course focuses on contemporary concerns, which are often generated out of the class’s interests. Here students apply their historical methodology or critical thinking skills to issues in everyday life or popular culture. Building on the idea that the historian of the future will look to visual documents to understand our times, we examine television and magazine images and apply the same critical thinking questions to them. Television news is particularly useful here. What is the newscaster saying? What are the sources? What alternative views are being ignored? How can we probe more deeply ourselves? Why are 80 percent of Nightline’s guest experts white males? What is the difference in coverage and interpretation of events in the Times of London versus The New York Times? Magazines are a valuable source of information too. Advertising aside (a whole different issue), what will the historian of the future make of the 4: 1 ratio of images of white, healthy-looking, middle-aged males over other people in most American news magazines (e.g., Time, Newsweek)?

The point here is, for historians teaching critical thinking, that we are not necessarily responsible for answering these questions; it is better to encourage students to seek out other history classes, or journalism, ethics, popular culture, and media classes, for some explanation. Our job should be to open their eyes to how one can turn the skills of interpreting and understanding the past to interpreting and understanding the present and, most importantly, to encourage in them the need to do so.

Many of us are aware of the move to present television news to public schools on a daily basis throughout many parts of the country. “Channel One” debuted as a test run in several schools throughout the country in March 1989. Created by Chris Whittie, head of Whittie Communications, “Channel One” is a twelve-minute national news broadcast (two minutes of which are commercials) beamed into school rooms on color television monitors through VCR and satellite dishes supplied by Whittle in return for required viewing by students. Critics have rightly opposed the daily doses of advertising. More pernicious, I believe, is the mask of objectivity such presentations will demonstrate. I think this pervasion of mass media is one of the most telling reasons for the implementation of critical thinking courses in our schools.

The 1988 Bradley Commission on History in Schools argues for increased critical thinking and historical content in education. I would agree here, and stress that it is not the stuff of history per se that is needed (although certainly that is a factor), but the tools of history, the questions and concerns, that we can take to our classes that is vital. Thus, it seems clear, we historians must teach critical thinking.

Finally, I find that the more I teach critical thinking classes, the better I teach my other classes. Thinking is infectious, and we should welcome the opportunity to share our skills with our students.

Linda Kelly Alkana teaches history and critical thinking at California State University, Long Beach, and humanities at the University of California, Irvine.