Every organization has a history. I’ve had the privilege of writing two such histories and co-authoring a third, one as a full-time assignment and two as a volunteer (and retiree). All three projects featured organizations in Kalamazoo County, in southwest Michigan, and benefited from Western Michigan University’s Archives and Regional History Collections. These experiences reinforced my belief that organizational history is not merely an antiquarian exercise; it is also a strategic resource for leadership and management looking to recognize past achievements and plan future objectives.

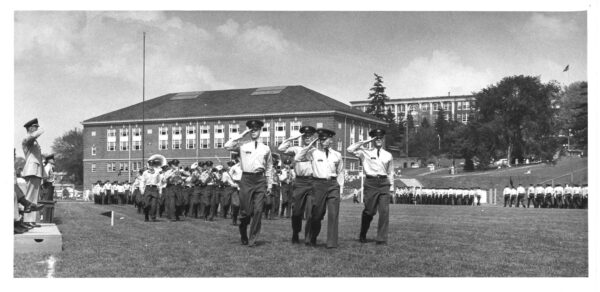

Tom Vance has worked on histories of Kalamazoo organizations, including the Department of Military Science and Leadership at Western Michigan University. Courtesy Western Michigan University Archives and Regional History Collections

In 2020, during the last six months of a 42-year career in public relations, I researched the history of my employer—the Kalamazoo Community Foundation (KZCF)—in preparation for its 2025 centennial. Though I was never a professional historian, a sense of history informed my working life. KZCF, a grantmaking organization, had abundant files documenting a century-long commitment to marshaling resources that support community nonprofits, including board minutes, booklets, and annual reports dating back to 1925—but no formal history. After consulting other community foundations that had celebrated their 100th year, I began conducting oral histories with 11 current and former presidents/CEOs and board chairs. Another 22 people outside KZCF provided information that augmented my research.

My aha moment came upon the discovery of Grace Thomas. A chamber of commerce volunteer, single mother, and insurance company employee, Thomas began researching the emergence of community trusts in 1924. (The first such trust, launched in Cleveland in 1914, aimed to become a “community savings account” by pooling resources from local philanthropists “for the mental, moral and physical improvements of the inhabitants of Cleveland.”) In August 1925, Thomas drafted the report that resulted in creation of the Kalamazoo Foundation. She went on to become Michigan’s first licensed female life insurance counselor.

Over time, the Kalamazoo Foundation’s name and mission changed with community needs, and the philanthropic model shifted from a small number of estate bequests to thousands of donors at all giving levels. From its origins in the research carried out by one determined volunteer, KZCF grew to become the most trusted philanthropic institution in Kalamazoo County and one of the largest community foundations in the nation.

The benefits of this work could be felt immediately.

A century after Thomas’s inquiry, my research resulted in a 48,000-word narrative accompanied by an appendix that includes the first 50 donors and grantees, a timeline, historical listings of trustees and staff, endnotes, and numerous photographs. KZCF featured my work online in a visual timeline, and I shared what I’d learned with the Council of Michigan Foundations in a virtual presentation titled “Enhance Your Anniversary Celebration with History.” The benefits of this work could be felt immediately: During the research phase, when staff proposed a new way to award grants, I could reveal that this was in fact how early grants were awarded.

This was not my first experience with organizational history. Prior to working for KZCF, I served as the community relations manager at Portage Public Schools (PPS) while pursuing a master’s in history. To fulfill the professional field requirement for my degree, I conducted oral histories with 11 former superintendents and board chairs. I returned to this project in 2019, joining the PPS centennial committee alongside representatives from the community, faculty, staff, and students. Portage District Library’s local historian Steve Rossio provided guidance on available resources, and we benefited from an illustrated booklet published for the school district’s 75th anniversary.

Western State Normal School (later Western Michigan University) was instrumental in turning PPS (founded in 1922) into a training site, providing a superintendent and faculty while the township provided facilities and supplies. Cleora Skinner—whom we believe was the first woman K–12 superintendent in Michigan—led the district for 17 years. Another surprise was the discovery of two Black student teachers (then called “practice teachers”) at a time when the district served a largely white, rural farming community. One student teacher, Merze Tate, became the first Black woman to graduate with a bachelor’s degree from Western State Normal School and went on to a distinguished career as a diplomatic historian. In 2021, WMU named one of its colleges after her.

PPS began its centennial observance with a series of short articles published in the district’s monthly newsletter from August 2021 through December 2022. The 10,000-word history was completed in time to share with the graduating class of 2022 as a 28-page booklet. Additionally, a collection of three new oral histories, newspaper reprints, and the 17 monthly articles became The Centennial Anthology: Portage Public Schools, 1922–2022, edited by Nicholas Meyle, a commissioner of the Portage Historic District.

That same year, in fall 2022, the Department of Military Science and Leadership at WMU began planning for its 75th anniversary, which would take place in 2025. A fellow alumnus, Mike Evans—retired from a career in banking with a master’s in history—and I volunteered to produce a history. Commissioned as second lieutenants in 1978 from the Army’s Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) at WMU, we both serve on the Department of History’s Alumni Advisory Council. Though a total of 1,720 lieutenants have been commissioned from WMU since 1950, the only published record of this history was a brief posting on the school’s website. We began our search in WMU’s archives, which house yearbooks, commencement programs, undergraduate catalogs, university publications, news releases, photo files, and student newspapers. Thanks to WMU’s ScholarWorks digital repository, we could do much of it virtually.

Evans developed a comprehensive alumni database, while the ROTC hosted an online form for alumni to submit information. Within two years, he had made contact with 83 percent of graduates, and had researched, written, or edited 1,144 one-page biographies of former cadets and department heads accompanied by more than 2,000 photos. Evans created graphs tracking demographics such as the impact of the draft on ROTC enrollment during the Vietnam War and the number of female cadets and seniors in the program each year. His work also includes an alphabetical listing of all WMU ROTC graduates.

Meanwhile, I conducted 12 oral histories with alumni from different decades and three department heads. The 12,900-word narrative includes 22 photos, citations, and a brief chronology; sections on each decade describing curriculum, school-year field training, summer training camps, and alumni memories; and a From the Archives section with a variety of documents. The appendix features a detailed timeline, a listing of professors and instructors, cadet commanders, Wall of Fame recipients, a glossary, sources, and a selection of Evans’s graphs. Together, the biographies and narrative constitute the “75th Anniversary History of WMU Army ROTC,” a project completed in time for the anniversary event, which included 300 attendees from across the country. A set of nine binders was donated to the ROTC, another set to the university archives, and PDFs of the work will be posted on the program’s website.

Two examples illustrate the early impact of the WMU ROTC project. Almost immediately, historic information about the program’s rappelling towers helped the Department of Military Science and Leadership gain support for a new tower. A long-term benefit came after the family of a 1954 alum who responded to our outreach effort—but died shortly thereafter—made a substantial gift to the department based on their gratitude for this reconnection. Numerous other alumni have expressed their appreciation for being included.

All three projects described here set aside adequate time for thoughtful research. I began the history of KZCF five years ahead of the organization’s 2025 centennial. I had two years to prepare for the PPS centennial and three years for our account of the WMU ROTC. Each project involved a review process: KZCF drafts went through a cross-functional team, PPS drafts were shared with the centennial committee and ultimately approved by the superintendent, and the ROTC biographies and program history were shared on a regular basis with a monthly alumni group and the department. Two key takeaways from these experiences stand out. First, oral histories are vital. While time-consuming, these conversations provide rich details for building a narrative and strengthen an organization’s connection with the individuals who have both contributed to and benefited from its mission. Second, deciding how to arrange each narrative was a significant consideration: The KZCF and PPS projects were organized along their stages of development, while the ROTC narrative was structured simply by decade, since that is how alumni would use the information.

Oral histories provide rich details for building a narrative and strengthen an organization’s connection with individuals.

All three organizations believe the histories served their purpose. KZCF’s narrative facilitates donor and grantee communications. In addition to being a souvenir for the class of 2022, the PPS narrative instills pride within the school community alongside appreciation among taxpayers and voters. The ROTC research conducted with Mike Evans helped build morale among the cadets, cadre, and alumni; it could also serve as a case study in ROTC training. Making these histories available strengthens the identities of the organizations while providing context for how they fit into the history of a community—in this case, Kalamazoo County.

Historical scholarship was not necessarily part of these organizational cultures (apart from the PPS history faculty), but all three provided enthusiastic support. And though research methods for each project met scholarship standards, some readers may question the objectivity of organizational history. Especially in the case of milestone anniversaries, frank narrative must be balanced by the aspirational intent of the end product, which seeks to both commemorate and celebrate an organization’s vision and mission. This is precisely the value proposition for public and private sector leaders: Knowing an organization’s history can help achieve its mission and vision. Since all organizations have a history, learning from that history should become organizational best practice.

Tom Vance is a retired lieutenant colonel in the US Army Reserve. The author thanks Lynn Houghton, regional history curator, and John Winchell, archives curator, at Western Michigan University’s Archives and Regional History Collections.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.