Each year, in a tradition dating back over a century, major league clubs head to warm locales in the southern United States to play baseball before the regular season starts. And each year, in a tradition dating back almost as long, hometown fans and newspaper reporters follow. The history of spring training is a history of both business and media.

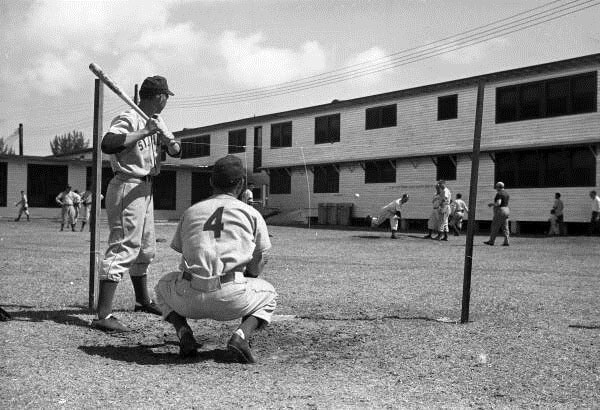

The Brooklyn, and later Los Angeles, Dodgers held spring training in Florida for over 50 years, until they moved to Arizona in 2009. Florida Memory/Flickr

Before the Grapefruit League, which currently consists of 15 major league baseball clubs who conduct their spring training in Florida, and the Cactus League, consisting of 15 clubs training in Arizona, spring training was a more spontaneous affair. In 1870, a year after becoming the first fully professional team in baseball, the Cincinnati Reds started their second season by going down to New Orleans and playing the first games of the season in the South. The Chicago White Stockings, which later became the Chicago Cubs, also started that season in New Orleans. Over the next decade, more professional and amateur teams started heading to cities in the South to kick off their seasons. As Charles Fountain describes in Under the March Sun (2009), spring training in this period was mostly about conditioning rather than improving baseball skills. Players spent their days taking long hikes or doing bodyweight exercises to lose the weight they’d gained over the winter and to get back in shape for the season. Not all teams planned for spring training far in advance, or even participated in it.

Scholars disagree on the origins of spring training as an organized and regular institution. Larry Foley, professor and chair of the journalism department at the University of Arkansas and the director of the documentary The First Boys of Spring (2015), says there is little question about Hot Springs, Arkansas, as “being the place where the idea of spring training really took off.” In 1886, Cap Anson, the player/manager for Chicago White Stockings, took the players to Hot Springs to train before the season began. Hot Springs was an ideal location both because of its warm weather and its springs, which helped players recover from training.

After the White Stockings’ successful 1886 season, when the team won the National League pennant, spring training became a more or less regular part of its schedule. Soon, other teams—major league teams, minor league teams, and Negro League teams (including the Kansas City Monarchs and the New York Black Yankees)—started joining Chicago in Arkansas. Fountain argues that while Cap Anson gets the credit for starting spring training due to the White Stockings’ championships and because he “brought along a newspaper reporter to publicize the trip,” the earlier trips down south were actually the true precursor of modern spring training.

By the early 20th century, according to Fountain, more teams recognized the need for spring training, and some even began to think of it as a marketing opportunity. In 1906, John McGraw brought his 1905 World Champion New York Giants to Memphis, where he drew attention to his team by escorting players on horse-drawn carriages and claiming that the team would win the championship again in 1906 (that title, however, went to the Chicago White Sox). In 1907, the Giants’ spring training in Los Angeles generated significant newspaper buzz in New York, causing other teams to try to generate similar results.

As newspaper writers described pitchers and other players getting back in their stride during spring training, they also hyped up Florida. As early as the 1920s and 1930s, affluent fans made spring training towns their “winter vacation destinations,” writes Fountain. Other fans also found ways to follow their teams around. The Boston Red Sox, for example, have held spring trainings at a number of sites over the last century, including Hot Springs; New Orleans; Winter Haven, Florida; and, more recently, Fort Myers, Florida, where the team has trained since 1993. For many of these years, according to Foley, the Royal Rooters, a dedicated Boston fan base, would “hop on the train and go down and spend several weeks watching the team.”

The club owners and managers weren’t the only ones thinking about the attention and money spring training could bring. Al Lang, who was mayor of St. Petersburg, Florida, from 1916 to 1920, predicted that spring training would have a positive impact on the city. In Fountain’s words, Lang thought that “spring training would make St. Petersburg a tourist mecca.” To this effect, Lang, an avid businessman and baseball fan, put significant resources into building spring training facilities and recruiting teams to train there, first the St. Louis Browns in 1913 and then the Phillies in 1915. For the 1925 season, Lang convinced the Yankees’ owner Jake Ruppert to bring his team to St. Petersburg from New Orleans. This was a relatively easy sell, as Ruppert was looking to take Babe Ruth away from the temptations of New Orleans. According to Fountain, once the Yankees moved to St. Petersburg, the town “became the unquestioned center of the spring training universe; for wherever Babe Ruth went, newspaper writers followed.”

In the mid-20th century, Jim Crow affected some of the major league clubs’ business decisions regarding spring training. By the mid-1950s, over 10 percent of major league baseball players were African American. Spring training facilities in Florida were, however, highly segregated, and often led to humiliating experiences for black players who couldn’t eat or sleep in the same places as their white peers. Pressure from the NAACP and black journalist Wendell Smith (famous for reporting on Jackie Robinson during his 1947 rookie year) encouraged some teams to relocate to new spring training sites where the team could access integrated facilities. Branch Rickey chose Vero Beach in Florida for the Dodgers’ spring training in part because he could control the housing and dining sites and his players would be able to live and eat together. In fact, the birth of the Cactus League can be traced to these efforts at integration. One of the reasons Bill Veeck is reported to have moved the Cleveland Indians to Arizona in the spring of 1947 (joined by the New York Giants that year, too) was that he expected Arizona to be more welcoming to black players.

Fountain suggests that for much of the history of spring training, teams were more concerned about its cost to the team. But by the 1970s, clubs began paying more attention to the “money generated by spring training.” A 1987 study by the Florida Department of Commerce, Fountain notes, found that the financial impact of the Grapefruit League was $295 million. In 2000, Governor Jeb Bush approved a law that would put $75 million of public funds toward spring training facilities. According to Fountain, most spring training complexes in Florida and Arizona have used public money.

Today, these numbers are even higher. The Florida Sports Foundation reports an annual economic impact of $753 million per year for Florida from spring training games. The Arizona Sports and Tourism Authority reports an estimated economic impact of $450 million per year from Cactus League games. In the modern era of spring training, clubs sell packages to get fans out to Florida or Arizona. Every few years, new spring training facilities crop up. In 2017, the Washington Nationals and the Houston Astros moved into their new spring training home in West Palm Beach, Florida. The Atlanta Braves will move into its new facility in Sarasota County, Florida, in 2020.

But through all these changes, there are some aspects of spring training that have remained the same since its inception. Spring training games give managers and coaches an opportunity to see how their players are performing in the new season, individually and together, and to consider which minor league prospects they may bring up. And perhaps most importantly, for all of us fans, spring training is the first sign that baseball is back.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.