Undergraduate teaching offers many historians their widest audiences, as well as some of the most direct opportunities to maintain the discipline’s presence in the public consciousness. In light of the recent downward trend in the number of history majors (see the March and May 2016 issues of Perspectives on History), and anecdotal reports from some department chairs that overall undergraduate enrollment in history courses has been falling, the AHA conducted an online survey to gauge trends in student enrollment in college history courses.

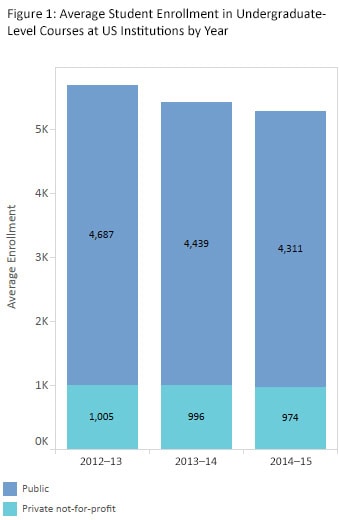

Figure 1

Conducted this past spring and summer, and targeted at chairs and program administrators from colleges and universities in the United States and Canada, the survey aimed to measure the changing popularity of history courses. Responses show that the total number of college students taking history courses—a broad measure of our discipline’s reach in higher education—has fallen over the past few years. The direction and degree of enrollment changes vary significantly from institution to institution, with public institutions more consistently affected by declines. Initial analysis does suggest, however, that historians at many institutions might be able to support higher levels of student interest in undergraduate history courses with greater outreach and broader faculty participation in recruiting students.

E-mails and postings to the AHA’s Department Chairs community invited more than 800 academic units at a variety of institutions to participate in the online survey. Based on the composition of academic units that elect to be listed in the AHA’s Directory of History Departments, Historical Organizations, and Historians, the survey invitations went disproportionately to administrators in departments at four-year institutions, although the AHA made a parallel effort to recruit responses from units at two-year institutions. Of those who submitted at least some enrollment information, 113 were at four-year institutions in the United States, five were at two-year institutions in the United States, and five were at four-year institutions in Canada. Another 30 respondents began the survey but stopped before submitting any quantitative information. Institutions represented within the category of four-year institutions varied greatly by retention and graduation rates, size, public or private control, types of undergraduate programs offered, location, selectivity, Carnegie classification, and institution level (from baccalaureate-only to PhD-granting). The aggregate number of undergraduate history students represented in responses to this survey was approximately 390,000 in 2012–13 and approximately 360,000 in 2014–15.

From the 2012–13 academic year through the 2014–15 academic year, overall student enrollment in undergraduate-level history courses declined at 96 of the 123 academic units for which we now have data. Total undergraduate student enrollment in history courses rose at only 27 of these institutions. Worryingly, large net declines of 10 percent or more affected 55 of the responding institutions. The median drop in enrollment at public institutions was somewhat higher (9.2 percent) than the median change at private institutions (7.9 percent; see fig. 1). The experience of individual departments in each category, however, varied widely. One private institution saw a 29.8 percent increase in history enrollments, while another saw a 42.1 percent decline. One large public institution’s history enrollment dropped 26.4 percent, while another smaller public institution’s rose by 23.8 percent.

Academic institutions in the survey reported that, in aggregate, undergraduate enrollment in all history courses in 2014–15 was 7.6 percent lower than it had been in 2012–13. The corresponding decline in enrollment in introductory-level history courses was only 4.8 percent, suggesting that, while student experiences in lower-division courses might not encourage them to take additional history courses, these courses are not solely responsible for the decline across the discipline; a greater proportion of the falling enrollments is actually occurring in upper-level history courses.

While student enrollment trends might interest the vast majority of history faculty members, the survey shows that recruiting students to take history courses or to major or minor in history is not assumed to be an integral part of instructors’ responsibilities at many institutions. The survey data suggest there may be opportunities, especially at large institutions, for historians to take a more active role in advocating for their own discipline with undergraduate students.

An AHA survey shows that the total number of college students taking history courses—a broad measure of our discipline’s reach in higher education—has fallen over the past few years.

According to half of our respondents, a minority of instructional faculty recruit students to take history courses or encourage existing students to take more history courses or choose a history major. When asked “How many of the instructional faculty in your academic unit or department actively recruit students or majors?” and instructed to include tenured, tenure-track, and non-tenure-track or contingent faculty members in the estimate, 42.2 percent of respondents answered that “a few/less than half” of their faculty colleagues participated in direct efforts to sustain student enrollment, and 7.8 percent responded that “none” did. At 11.2 percent of institutions, “approximately half” of instructional faculty were involved; at 24.1 percent “most” participated, and at 14.7 percent “all” did. A few respondents were not sure whether or how many of their colleagues actively recruited students.

The size of the department also correlated with whether faculty were more involved in student recruitment. Those who reported limited faculty involvement tended to be in larger academic units (in terms of the number of full-time-equivalent faculty members), while those who reported full faculty participation tended to be in smaller departments. In optional comments on this question, a few respondents detailed systematic strategies to maintain and increase student enrollment, and a few more explained that they were working on the problem. Some further clarified that their reliance on contingent instructors to teach limited the number of people who felt invested in recruiting students to take history courses at the institution. Others suggested that they found this a strange or even inappropriate role for most faculty, with one writing, “Recruitment is largely handled by a staff adviser,” and another, “We have not historically actively recruited within the department.” A few reported that student recruitment was the responsibility of the department chair or undergraduate program coordinator. Several stated that they did not understand the question. One respondent expressed cynicism about the issue of faculty participation in student recruitment—“Yeah, right”—although it was unclear whether this indicated discouraging faculty attitudes toward the task, existing demands on their time, or lack of support or opportunity at the institutional level.

Department personnel did say that they use a range of tools to reach students with a message about the value of studying history, although faculty might not be venturing far afield to find new students. From a list of 15 different types of potential recruiting activities, respondents identified the one with the highest level of faculty involvement as “Participate in recruiting events on campus (i.e., tabling for history at first-year orientation events),” with 92.4 percent indicating either that faculty in their departments did this “somewhat” or that it was “an area of emphasis.” Talking to current students in groups (addressing a classroom or event attendees, for example) was the second most popular recruitment method at 89 percent, followed by initiating individual communications with current students (writing a personalized letter or e-mail or scheduling an in-person appointment to talk to a particular student) and distributing printed materials marketing history courses (fliers or brochures distributed outside the department); 77.1 percent did each of these. On the other hand, only 12.8 percent responded that their faculty participated in programs with elementary school students “somewhat” or that this was “an area of emphasis”; 17 percent reported visiting high schools; 26.5 percent visited courses or events in other departments or programs to talk about history offerings; and 29.3 percent communicated directly with faculty or staff at community colleges whose students transfer to their institutions. More creative approaches to social media and to developing web resources and marketing materials, as well as communication between history faculty and other campus staff, like academic and career advisers, had a middling level of uptake at departments.

There was a slight positive correlation between an institution’s selectivity and the rate of change in history enrollments, but this probably tells us more about the resources of the institutions involved and the curricular expectations among students who attend them than about how historians elsewhere can improve their outreach. Similarly, colleges and universities in the Southwest region of the United States seem to have had a slightly better record with history enrollments over the past few years than those in the Midwest, but location is generally a fixed characteristic, so this observation—most likely reflecting national demographic trends—is not helpful for departments looking for effective strategies to increase enrollment.

While the current scale of history instruction is shrinking at most institutions, the levels of self-reported departmental activity in recruiting students to learn history may be encouraging: we have not, as a disciplinary community, exhausted all available options. As instructors and other interested historians look for solutions, the AHA and its tools are available to help share ideas and resources to advance the cause of undergraduate history education.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.