The phrase “We learn from each other’s stories” seems like a simple statement, but yank the thread and out tumble events, motivations, and all the drama of the human condition. Renowned historian Thomas Bender argues that the specializations within social history (and their micro-level stories) have fragmented our understanding of the American past, as historians no longer provide the grand-arc narratives critical to public discourse. He also emphasizes how historical writing “became more analytic” as we began to write for ourselves rather than our students. Far from castigating, Bender explains that “scholarship of the past couple of generations is too valuable to keep to ourselves,” as he calls for a new “synthetic narrative of who we Americans are as a people and how we got be so” as a way to “contribute to the construction of a more democratic and inclusive public culture.”1

As part of this laudable goal, I turn the conversation toward the ways in which historical insights from studies of diverse populations can deepen the panorama of a national narrative. They can offer fresh interpretations, methodologies, and even sources to the practice of history. Taking a place-based approach, I profile two “good reads” and one public history project that exemplify archival imagination through layered, interdisciplinary perspectives; in so doing, these works draw the reader into the shifting social and political worlds of their protagonists, revealing bonds of community, kin, and remembrance.

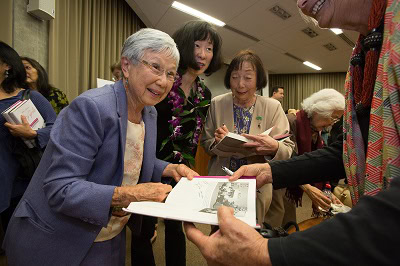

Rose Honda (left), a member of the Windsors club and adviser to the Atomettes, signs copies of City Girls with author Valerie Matsumoto (center) and Atomettes member Sadie Hifumi (right). Credit: Reed Hutchinson/UCLA

In The Sea Is My Country, Joshua Reid takes readers on a “forensic voyage” as he chronicles the history of the Makahs over three centuries, focusing on their impact on settler colonialism in the Pacific Northwest and Canadian borderlands. Telling the Makahs’ history from indigenous points of view, Reid elegantly demonstrates how they were major players in the “middle ground,” wielding real authority before, during, and after European contact, through artful political maneuvering, control of trade, and deep maritime knowledge. Reid offers portraits of both courageous and flawed leadership, highlighting fluidity amid ruptures and transformations instead of mere declension. In his discussion of 20th-century struggles over fishing rights, he explains, “Amid the vicissitudes . . . we should not characterize the Makahs as simply responding to forces beyond their control. Instead, this history . . . illustrates the ways . . . leaders and families took action to retain what was important to them—the sea and the resources it provided[.]” Flipping the gaze allows Reid to perceive archival inflections other scholars might have missed; he brings out how multiple generations have striven for self-determination for the Makah by relying on their maritime intelligence, bonds of community, and embrace of modern technology to influence and, indeed, shape the worlds around them. In the book’s foreword, the tribal council puts it more bluntly: the stories within The Sea Is My Country “are not new to us.”2

In contrast to the warm reception Reid has received, contemporary Cherokees have had a mixed reaction to Tiya Miles’s award-winning nonfiction narrative Ties That Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom. Her intimate study of the crucible of kinship and slavery challenges how historians teach about the relationships among the Cherokee, enslaved Africans, and Afro-Cherokees. Known only through scraps of evidence—a bill of sale, her petition for a military pension, the anecdotes of European American and Native American observers—Doll, the servant-wife of the prominent warrior Shoeboots and mother of their five children, emerges as a full-fledged historical actor in the author’s skillful reconstruction of her life. Like a good mystery writer, Miles leaves the reader guessing throughout the text—will Doll ever gain her freedom or even be accepted by Shoeboots’s female kin? Will her daughter Elizabeth preserve her freedom as a homesteader in Oklahoma? Boldly using Toni Morrison’s Beloved as a model, Miles seeks to recreate Doll’s interior world and decision making. But more importantly, she lays bare the horrors of bonded labor, bringing to the fore the racial formations that went hand in hand with Cherokee attempts to maintain their land and sovereignty, even beyond removal. Kinship was the key to Cherokee citizenship and protection for Afro-Cherokees. Shoeboots understood this concept well as he secured tribal citizenship for his three oldest children, but not for Doll. Her life was a pendulum that swung between slavery and freedom. In Ties That Bind, Tiya Miles transcends the limits of the archive in her quest to reveal the power of kinship and belonging.3

“We believe that our collective history is more diverse and multi-faceted than most people give credit for.”

Who makes history? As educators, we connect our students and the public with the past. For over three decades, I have assigned hands-on research projects—traditional research papers, field trips, oral history projects, and even scrapbooks—all with varying degrees of success. However, the History Harvest takes experiential learning and storytelling to an exciting metalevel. Co-directed by William G. Thomas and Patrick D. Jones, historians at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, this digital project has at its core faculty-mentored student teams that plan and manage a “harvest” by inviting members of a specific Great Plains community to share their memories, photos, and family treasures. Interviews and artifacts are then classified, interpreted, and uploaded onto an open access web-based archive.

The History Harvest preserves, transmits, and connects its digital treasures to larger communities, including scholarly ones. The core collections represent an ever-growing resource for future articles, dissertations, and books. Given its success, this initiative has inspired similar efforts across several states. Indeed, it answers the clarion call put forward by Bender as well as by two former AHA presidents who served approximately 80 years apart. In 1931, Carl Becker spoke of the importance of a “living history,” a construct that William Cronon would later build upon in his influential essay on the centrality of the story in our scholarship.4 And the History Harvest’s mission statement resonates deeply with my own work:

We believe that our collective history is more diverse and multi-faceted than most people give credit for and that most of this history is not found in archives, historical societies, museums, or libraries, but rather in the stories that ordinary people have to tell from their own experience and in the things—the objects and artifacts—that people keep and collect to tell the stories of their lives.5

In a recent essay, Thomas went further as he explained how the History Harvest contributes to a wider conversation on the future of higher education: “Central to the future of the humanities and, indeed, to the future of the liberal arts and sciences is developing students as producers in the digital medium, rather than only as consumers of digital content.”6

Whether located in digital archives, public history programs, or even in books, bonds of remembrance breathe life into history as they connect generations. Such bonds were on full display at an event celebrating Valerie Matsumoto’s City Girls: The Nisei Social World in Los Angeles, 1920–1950, as several senior citizens who appear in the book took their turns at the podium. They underscored the significance of women’s community networks, which began in a prewar culture of girls’ clubs, from wartime incarceration through postwar resettlement. With names that conveyed more innocence than irony (such as the Atomettes), these clubs, members explained, provided more than a sense of belonging: they served as sources of support, information, and mutual aid, not to mention enduring friendships. Their punctuation of the author’s thesis did not end there. In a collective act of ownership, the “city girls” took their place alongside Matsumoto during the book signing—adding their signatures next to hers. Their participation sent a clear message to the largely student audience about how the past is ever present. Or, as the late Peggy Pascoe explained, “I understand history as a kind of conversation between the past and the present in which we travel through time to examine the cultural assumptions—and possibilities—of our society as well as the societies before us.”7 And therein lies the power of a good story.

Notes

- Thomas Bender, “How Historians Lost the Public,” Chronicle of Higher Education, April 3, 2015, B4–5. [↩]

- Joshua L. Reid, The Sea Is My Country: The Maritime World of the Makahs (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015). Quotes are from pp. 252 and vii, respectively. [↩]

- Tiya Miles, Ties That Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). Miles has also published a historical novel, Cherokee Rose (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair Publisher, 2015). [↩]

- William G. Thomas III, “Teaching and the Digital Humanities,” Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 68, no. 4 (Summer 2015): 32–33; William Cronon, “Storytelling,” American Historical Review 118, no. 1 (February 2013): 1–19 (quote is from p. 7). [↩]

- History Harvest, accessed October 8, 2015 [↩]

- Thomas, “Teaching and the Digital Humanities,” 32. [↩]

- Valerie J. Matsumoto, City Girls: The Nisei Social World in Los Angeles, 1920–1950 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014); Peggy Pascoe, Relations of Rescue: The Search for Female Moral Authority in the American West, 1874–1939 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), xxiii. [↩]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.