Classes have ended, grading is complete. The intellectual delights of summer loom. Now is the time to catch up on serious in-depth reading, sift through foreign-language journals, concentrate on challenging secondary sources, check footnotes for articles ready to submit, and confirm references missing from an article one has been asked to referee. These are routine matters for those with permanent academic employment or on long-term contracts.

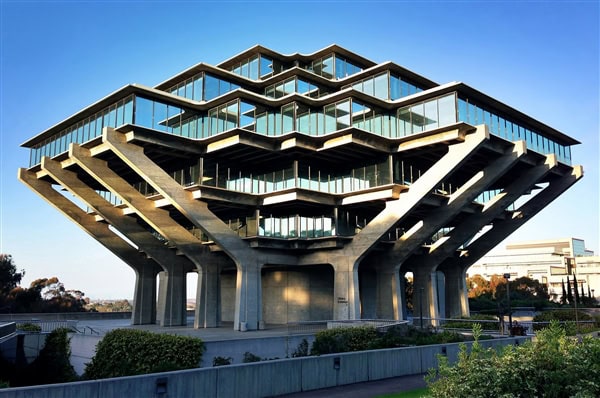

If there was ever a literal ivory tower in academia, it would be the university library. O. Palsson/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

But for those who string together academic appointments and who regularly scramble for access to research libraries, such activities are not possible. At no time is the divide between privilege and lack of privilege more evident than over the summer when few people show up on campus, and those lucky enough to work in foreign archives run into each other at coffee breaks.

There are indeed many ways to be a historian, and almost all of them require library access. AHA has issued a strong statement on this pivotal issue of library access, an issue that can advance or stifle academic careers, but there have been few subsequent steps despite repeated calls for action in these pages.

The problem is real and the impact acute. How bad is it? If you can’t get into a library, you can’t work on requested revisions, prepare a new course (even on spec), or improve an imminent conference paper. You can’t enhance an application or read the work of a colleague you might expect to meet. There have indeed been major strides: JSTOR, for example, is widely available at a manageable price. But much other material necessary for a career in scholarship remains behind paywalls, and even those willing to purchase library access are often turned away.

“Independent scholars” are in fact highly “dependent scholars.”

These days many primary sources are digitized and freely available online, but the scholarly books and articles that interpret them are not. Premodernists and historians working in non-Anglophone fields often rely heavily on transcriptions, translations, and critical editions of their material in print, items that are expensive for an individual to purchase and hard to find. Whatever open access initiatives might promise on the horizon, they do not provide near-term solutions. The euphemistically termed “independent scholars” are in fact highly “dependent scholars.” They necessarily rely on others to copy and photograph documents, write letters of introduction to support requests for library access, and to allude (often vaguely) to cooperative ventures. They or their patrons must conjure up accounts of what amounts to “research peonage” to get them into real and virtual halls of learning. Even when such efforts succeed, this expenditure of social capital is demoralizing (a separate topic worthy of consideration), but in many cases they do not.

Of course, the AHA cannot take unilateral action or require any institution to act. But it does offer a bully pulpit, and our leaders can articulate and model appropriate behavior. If the AHA would set standards and expectations, gig-dependent and alumni scholars could then call out their own institutions and inquire how they respond to disciplinary standards.

Every contingent scholar has stories about successful work-arounds and varied strategies, but none of them last for long and most can’t be repeated year after year. Most of them depend on personal connections and who you know. Many hesitate to share their success stories widely. Those with the power to grant access generally do not want it known. One sympathetic senior scholar said to me, “I would rather look bad in print than be overwhelmed by the number of requests I would get if you mentioned me and my institution kindly.” This is indicative of the extent of the problem.

The problem affects gig-dependent historians of all ages. Of course, the best means for gig-scholars to enter a brick, mortar, and stone library with actual bookshelves is to get a short-term appointment of some kind, but many of those specifically exclude summer-only positions. Barring that, these peripatetic historians spend days in the autumn and spring madly downloading material to read later.

The pandemic has made matters worse. Many of our great research libraries (whether university, museum, institute-affiliated, or independent) cut back access significantly during the pandemic, and few have reopened to those without formal appointments. Historians without a metaphorical union card for the academy are stuck.

Younger, energetic gig-scholars do heavy lifting or office work, run errands, or deliver baked goods (the “lawn mowing for libraries” exchange).

For online access to obscure items, these desperate scholars barter for other people’s login details. I’ve known emeriti with limited access who share their home with grad students and piggyback on their university privileges. Younger, energetic gig-scholars do heavy lifting or office work, run errands, or deliver baked goods (the “lawn mowing for libraries” exchange). The more fortunate middle-aged ones occasionally use their children’s or neighbors’ high school logins—although those too, rarely work over summers.

Dependent scholars have put together Twitter accounts to facilitate article access, a form of mutual aid necessitated by the inability of many researchers to access scholarly resources. These accounts enable underresourced and frustrated scholars to tweet full bibliographical article references in the hope that some followers can provide them by direct messaging. Others find requests made through book exchange Facebook groups more effective.

These are stopgap measures. It is time for the AHA and other learned societies, in partnership with libraries and scholarly institutions, to advocate in specific ways for scholars and scholarship that extends beyond the employed and tenured elite and their enrolled graduate students. Some suggestions follow to address this immediately and at reasonable cost.

One solution would be for any appointment of less than six months to come with library access for six months, and any appointment for up to twelve months come with library access for a full year. That would permit many academics to continue their scholarly research even during intermittent strings of short-term postings. Another would be for libraries to provide, maintain, or enhance access for alumni (some do, many don’t). A third would be for libraries to expand their programs for visiting scholars and offer fellowships not just to consult their rare book rooms in person, but also to work virtually.

It isn’t just institutions with formidable resources that could step up. Local colleges as well could offer summer “bridging fellowships” for online access to their library collections and raise their profile at the same time. Institutions could join together and publicly make an access pledge appropriate for their size and circumstances.

Finally, peer reviewers at journals should be sensitive to this issue. Anonymous review meant to result in a wider, more diverse array of contributors to intellectual discourse won’t work if potential authors are required to include references to material they cannot access. Editors should consider attaching links or downloads to scholarship they ask the author to cite in revise-and-resubmit letters.

These are modest proposals. No one is asking university libraries singlehandedly to solve the crises in publishing or academic employment. But academic departments, scholarly societies, and funders, please take note. Access to books, databases, and journals shouldn’t simply depend—as now—on who you know or who your spouse is. Pay attention to those on the margins of academic employment, who are all-too-often demoralized, excluded, and ignored. They are historians who also read and write.

E. M. Rose’s most recent appointment as research associate ended May 31; her next position as visiting scholar begins at the end of September.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.