Stephan Thernstrom, the Winthrop Professor of History emeritus at Harvard University and a groundbreaking American social historian, died on January 23, 2025. Known for pioneering the use of quantitative data in historical scholarship, throughout his career he was driven by an underlying interest in the American dream’s promise of social mobility. In the 1980s and 1990s, Thernstrom and his wife, political scientist Abigail Thernstrom, became nationally prominent critics of affirmative action and advocates of educational reform.

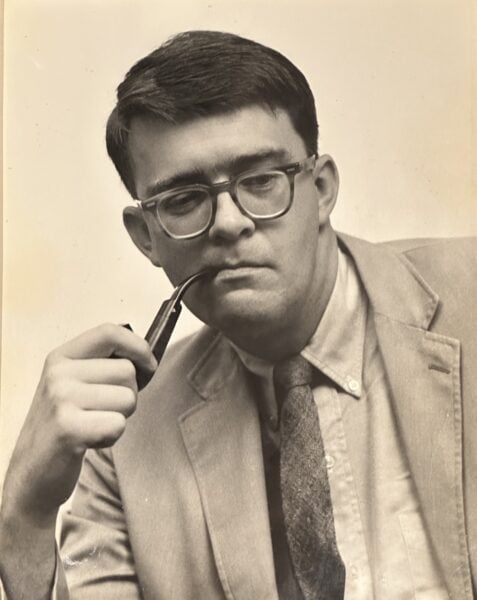

Photo courtesy Melanie Thernstrom

Born on November 5, 1934, in Port Huron, Michigan, Thernstrom saw in his own family history themes he would spend his life exploring. His working-class Swedish immigrant grandfather and his father worked for the Grand Trunk Western Railroad; his father climbed a career ladder from telegraph boy to Chicago division superintendent. Though Thernstrom was initially “a tremendous disciplinary problem” as a student, his life changed when he discovered a love for Latin and debate in high school. In 1956, he graduated from Northwestern University. To his father’s horror, Thernstrom became left leaning in college; he recalled his father saying, “If you’re a communist, I don’t want you in my house.” During his graduate studies at Harvard University, Thernstrom engaged in political protests and belonged to a Marxist study group. On a blind date, he met fellow leftist student Abigail Mann; they married six weeks later, in 1959. A student of Oscar Handlin, Thernstrom earned his doctorate in the interdisciplinary History of American Civilization program in 1962.

His dissertation became his first book, Poverty and Progress: Social Mobility in a Nineteenth-Century City (Harvard Univ. Press, 1964), which drew on census data, tax and savings bank records, and city directories to examine social mobility among working-class families in Newburyport, Massachusetts, from 1850 to 1880. Challenging earlier work on the city by W. Lloyd Warner, Thernstrom argued that the American dream of occupational mobility was not possible for most of the working class, but that they could achieve alternative measures of success through homeownership and personal savings.

Thernstrom’s trailblazing work continued with a new foray into quantitative methods in The Other Bostonians: Poverty and Progress in the American Metropolis, 1880–1970 (Harvard Univ. Press, 1973). He compiled such enormous amounts of data that analysis necessitated the use of cutting-edge technology: formatting and running towering piles of IBM punch cards through a mainframe computer. The Other Bostonians won the Bancroft Prize, and the American Historical Review lauded it as “the best and most ambitious analysis of social mobility yet to appear.”

Thernstrom was the editor of the Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (Harvard Univ. Press, 1980), the first comprehensive treatment of more than 100 ethnic groups (“from Acadians to Zoroastrians”) in the nation. The book won the AHA’s inaugural Waldo G. Leland Prize for the most outstanding reference tool in the field of history, as well as the Association of American Publishers’ R. R. Hawkins Award. All told, Thernstrom would produce 11 books, including three with his wife.

Together, the Thernstroms wrote America in Black and White: One Nation, Indivisible (Simon & Schuster, 1997), which celebrated the progress of Black Americans from 1945 through the 1970s and argued that subsequent affirmative action policies had undermined their success. The couple also co-authored No Excuses: Closing the Racial Gap in Learning (Simon & Schuster, 2003), which identified Black and Hispanic students’ educational disadvantages as the main source of ongoing racial inequality in this country and the most pressing civil rights issue of the day. For No Excuses, the Thernstroms won a Fordham Foundation Prize for Distinguished Scholarship and the Bradley Prize for Outstanding Intellectual Achievement. Over the years, Thernstrom served as an expert witness in more than two dozen federal court cases that dealt with claims of racial discrimination, perhaps most notably in Hopwood v. Texas (1996), which overturned affirmative action in university admissions in Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas.

During his career, Thernstrom taught at Harvard University, Brandeis University, and the University of California, Los Angeles. In 1973, he returned to Harvard, where he would be named Winthrop Professor of History in 1981 and remained until his retirement in 2008. In 1999, he became a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute. Former graduate students, including me, remember Thernstrom as a kind and supportive mentor who loved spirited debates, pastry, playing squash, and his family. Abigail predeceased Thernstrom in 2020. He is survived by his daughter Melanie, his son Samuel, and four grandchildren.

Nancy Elizabeth Baker

Sam Houston State University

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.