“Entangled Trajectories: Integrating Native American and European Histories,” the symposium that Ralph Bauer (Univ. of Maryland) and I organized earlier this month at George Washington University and the Mexican Cultural Institute, was the result of (at least) two desires. First, we wanted to gather together a group of scholars, specialists in a range of fields and from a multiplicity of disciplines, whose work reflects the fact that the history of early modern Europe and Europeans—if not the world—cannot be properly understood without a deep understanding of the history of Native America and indigenous Americans. These scholars recognize the embedded-ness of Native American history in global history, or even Native American history as global history.

A second desire was congruent with the fact that this symposium was organized under the auspices of the Early Americas Working Group, comprised of scholars in a myriad of disciplines from the Washington, DC, metropolitan area who work on the premodern Americas within a global context. We wanted to create an event that would spin strands connecting area institutions that support scholarship and education about early modern Europe and America and thereby foster community to support interdisciplinary scholarship and strengthen links between the “academy” and the “general public.”

Three overarching themes emerged from the proceedings with particular salience.

First, many of the papers considered the cultural formations that emerged from European and Native American entanglements, and I noted a profitable tension between frameworks that emphasized incommensurability and those that emphasized hybridity. Drawing on James Lockhart’s formulation about “double mistaken identity,” James Maffie proposed that the dialogue that took place in 1524 (and was recreated in a mid-16th-century text) between Franciscan clerics and Nahua elite shows the two groups talking past each other: their incommensurable metaphysics were respectively “truth-based” and “path-based.” Margaret Bruchac spoke about the Haudenosaunee and Algonkian peoples’ use of wampum as a ritual device for embodying ceremonial speech and memory, resolving conflict, and processing grief. While effective colonial leaders grasped the essentials of wampum diplomacy, later collectors who assessed the beads did not, lacking necessary context, and so “recovering wampum meaning necessarily reaches beyond the museum and outside the archive to include phenomenological visits to historical sites and meetings with tribal wampum keepers.”

Despite, and sometimes because of incommensurable frameworks, colonial cultures were quintessentially hybrid, characterized by a vast array of creative amalgamations of European and Native American elements. Hybridity was often a result of imperial dependence on indigenous knowledge. Molly Warsh demonstrated how colonial officials in Venezuela exploited not only the labor of indigenous divers but relied on their expertise for harvesting oyster banks that produced sought-after pearls. The Spanish appropriation of the Arawak term xaguey, signifying the underwater depressions that were habitats for desirable pearl-producing oysters, is a linguistic marker of this process.

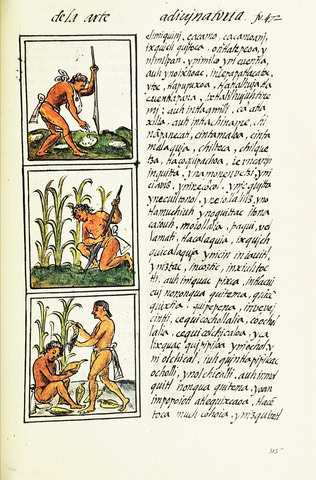

More often than not, hybridity and incommensurability were themselves entangled. Art historian Elizabeth Hill Boone, in her keynote address, “The Dilemma of the Gods and the Familiarity of the Kings,” showed the considerable divergence between renderings of Aztec lordship and Aztec divinity in the early colonial chronicles such as the Florentine Codex. The colonial texts facilitated transmission of preconquest notions of lordship; for instance in the images, thrones are fabricated with matted reeds that signified ruling authority in preconquest books (as pictured in this mid-16th-century depiction of the Aztec king Itzcóatlin the Tovar Codex). Yet, the ancient deities were more hybridized, constructed from an array of tropes, mingling European and Mesoamerican elements.

Representation of agriculture in the Florentine Codex. Credit: Gary Francisco Keller, artwork created under supervision of Bernardino de Sahagún between 1540 and 1585. – The Digital Edition of the Florentine Codex. CC BY 3.0

Second, the symposium revealed the sensorium as a fascinating and emerging realm in which to consider entangled trajectories. Barbara Mundy suggested how the smellscape of early colonial Mexico City may have been experienced differentially by Spaniards and indigenous locals. She evoked how the chinampas—the agricultural beds created by Nahuas in shallow waters of the lake—may have registered for different olfactory sensibilities: the decaying organic matter redolent of miasmatic stink for colonists, while fragrant with crop-producing fertility for indigenous locals. Neil Safier showed how a history of masks fashioned by Amazonian Yurupixuna to evoke animals—monkeys, frogs, feathered monsters, among others—can reveal different, though entangled, ocular and haptic realms. For Yurupixuna the masks belonged within a ritual, performative space where they helped participant-observers see the transformative nature of being, an extension of the reality in which spirits, the dead, and shamans assume animal forms. For Enlightenment naturalists, such masks were elements awaiting classification and display in a museum. The Italian naturalist Domenico Vandelli likened the masks to an “open book, in which the observer instructs himself easily and with pleasure, [and in which] memory is aided by the eyes, and attention is fixed through the pleasure of sight.” Warsh also hinted at the echo and scent of the sensorium by evoking the native divers who listened for rooting noises made by bivalves and the stinking fields of rotting oyster flesh, the detritus of pearl commodification.

Third, the symposium underscored that the backdrop to these novel cultural formations and sensory experiences was often annihilating violence, a systemic feature of Euro-American entanglements. Ned Blackhawk called attention to the cognitive dissonance produced by contemporary “genocide studies” that—remaining almost completely silent about massacres of American Indians—categorize genocide as a 20th-century phenomenon and one foreign to North America. Previewing her just-published book, Global Indios: The Indigenous Struggle for Justice in Sixteenth-Century Spain, Nancy van Deusen demonstrated that this violence rippled across the Atlantic, as she described efforts of Native American victims of the slave trade who fought for their liberty in Castilian courts by deploying legislation outlawing the enslavement of “indios.”

I’m grateful to my co-organizers, sponsors, speakers, and audience who put their time and energy into making the symposium the seedbed for continuing what Matt Cohen called a “multilingual, multi-contextual, north-south conversation” with “history, aesthetics, theory, and methodology all on the table.”

is associate professor of history at George Washington University. Her most recent publication is “The Chicken or the Iegue: Human-Animal Relations and the Columbian Exchange” in the February issue of the American Historical Review. She has been the convener of the Early Americas Working Group since 2013. The Early Americas Working Group is grateful for support from the Kislak Family Foundation, George Washington University, University of Maryland, Mexican Cultural Institute, and the National History Center that made possible the “Entangled Trajectories” symposium.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.