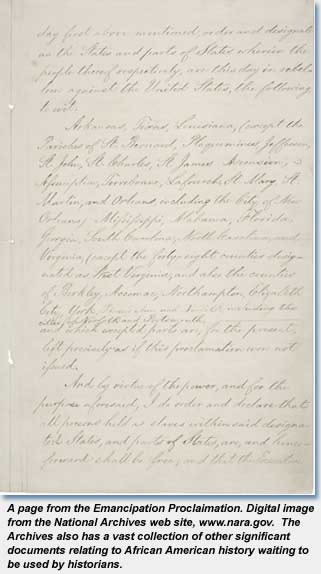

For scholars exploring African American history, a number of archival sources automatically spring to mind. The famous Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City, the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University, and the Amistad Research Center at Tulane University are well recognized for research in black life and culture. These are the repositories that most scholars of African American history will think of first. However, the National Archives is also a rich depository of documents relating to African American history.

In fact, as a repository of federal records, it is an unparalleled—if not often tapped—resource for such historians. As an evolving government's bureaucracy expanded to deal with a growing, multifaceted nation, it recorded—extensively, and in great detail—its activities. This fact did not go unnoticed by the American Historical Association while pleading its case to the U.S. Congress for an archives. The Association in 1910 adopted the following resolution:

The American Historical Association, concerned for the preservation of the records of the National Government as muniments of our national advancement and as material which historians must use in order to ascertain the truth, and aware that the records are in many cases now stored where they are in danger of destruction from fire and in places which are not adapted to their preservation, and where they are inaccessible for the administrative and historical purposes, and knowing that many of the records of the Government have in the past been lost or destroyed because suitable provision for their care and preservation was not made, do respectfully petition the Congress of the United States to take such steps as may be necessary to erect in the city of Washington a national archive depository, where the records of the of the Government may be concentrated, properly cared for, and preserved.

These federal records, which cover all the different periods of American history, are useful for research, investigation, and writing about American history in general and about African American life and culture in particular. From the early days of the republic, the U.S. government regularly dealt with issues concerning African Americans (especially because of the constitutional protections given to the institution of slavery) and left a paper trail that clearly marked and recorded the significant issues of race and class in American life and society—slavery, the international slave trade, the Civil War, white supremacy, segregation, and discrimination within the government and in mass society, as well as the modern struggles for civil and human rights.1

With the opening of the National Archives to the general public, November 11, 1935, this rich documentary heritage of the United States—in the form of the federal records—not only became permanently preserved but also became available for scholarship and research into America's past. Soon after the opening of the archives, the archival staff recognized that the archives had an enormous amount of records that documented African American history. Indeed, by 1940 the National Archives had undertaken—through the encouragement of Carter G. Woodson of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History and the American Council of Learned Societies—efforts to identify and describe records that pertained to African Americans.2

A few historians have made use of the extraordinarily rich documentation in remarkable ways. A most notable example is the massive documentary editing project undertaken by Ira Berlin and his colleagues, which culminated in Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861–1867, an enormous compilation with revolutionary implications for Civil War and Reconstruction history.3 But so rich are the federal records that they can be mapped and mined almost endlessly.

More than two hundred years of American governance have generated an enormous number of records, and therein lies the difficulty of research at the National Archives. Many scholars are intimidated by the very vastness of these archival holdings. And the holdings are not merely voluminous; they are also complex and often perplexing, as they echo the intricate and hierarchical structures of the bureaucratic networks that produced them in the first place. The interconnectedness of federal records often means that scholars feel lost in the maze of paper trails. Even the finding aids that the archives staff have been creating almost from the beginning seem ineffective and laborious to use. Yet, these records must be examined if scholars seek to study the complexities and politics of governing, the machinations of bureaucratic agencies, the opposition and support for government, the ambivalent stances of a nation unsure and uneasy about race, and the efforts to create a philosophy of race relations and civil rights.

Some scholars believe that research in the National Archives consumes a large quantity of time and resources while the results fail to match the research effort. There are even those who believe—wrongly—that the archival records are not relevant to the issues and questions they are pursuing. Scholars may think of NARA when they have a specific topic that they know is federally related; however, even then some become disappointed when they discover that the records are not always complete. Some scholars think that all the "good stuff" has been removed, or that "all the best records are classified and would take years for the Freedom of Information Act to gain access to them." Misinformation and misperceptions abound. Despite all these inhibitions, research in the National Archives can be exhilarating and rewarding, even if it is tedious and frustrating at times. If, for instance, one finds only a small amount of correspondence on some occasions, there will be other instances when a full run of letters, reports, studies, and assorted data can be located.

What can scholars do to minimize the hurdles of pursuing historical topics in the National Archives? Scholars should first use NARA's web pages to identify finding aids and records that may be of use to their research. Communication with the reference staff before coming to the National Archives is important, as is frequent consultation with the staff once at the archives. This can help researchers to use the finding aids more efficiently. Providing first-rate customer service is a principal NARA goal, and researchers should benefit from this expanded service. It would be useful also to consult the many bibliographic articles and books that discuss the records at the archives.4

The rise of a new information environment and the growth of the World Wide Web has meant that the National Archives too had to confront the major challenge for repositories of historical records these days—the question of the extent to which their holdings should appear on the Internet for scholars to access. Today's generation of students and aspiring scholars believes that everything should be on the Web. But this ideal cannot be realized in practice. The National Archives is placing an increasing percentage of its holdings on its web site. But the sheer volume of federal records precludes all of it being made available. Research in the old-fashioned way will thus have to remain, even as historical data on the Internet and the related searching tools grow and make it easier to discover new sources.

There is, of course, a necessary correlation between the amount and nature of available sources and research topics. Federal activity increased two-fold in the period immediately following World War II, with a proportionate increase in the number of records available for research. These records captured an amazing amount of information about postwar American society, and also about the modern civil rights movement (1945–65). Researchers studying U.S. history—especially 20th-century U.S. history—will thus find many new and valuable sources at the National Archives.5 Students of African American history will, in particular, find that more sources are now available. The need to explore these sources and expand upon topics is increasingly important. The holdings of the National Archives are a resource that truly needs to be considered in any investigation of African American and American histories.

—Walter Hill, who received his PhD from the University of Maryland at College Park, is senior archivist and a subject area specialist at the National Archives. He is also an adjunct professor of Afro-American studies at Howard University.

Notes

1. For a discussion of these issues as reflected in the U.S. Constitution, see Paul Finkleman, Slavery and the Founders: Race and Liberty in the Age of Jefferson (New York: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 2001); Don E. Fehrenbacher,The Slaveholding Republic: An Account of the United States Government's Relations to Slavery (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001); For a specific focus on the Constitution, see Finkleman, “Garrison’s Constitution: The Covenant with Death and How it Was Made,” Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives 32:4 (winter 2000).

2. See James R. Mock, “The National Archives with Respect to the Records of the Negro,”Journal of Negro History 23 (January 1938), 40–56; Roland McConnell, “Importance of Records in the National Archives on the History of the Negro,” Journal of Negro History 34 (April 1949), 135–152; and Paul Lewinson, A Guide to Documents in the National Archives for Negro Studies (New York: American Council of Learned Societies, 1947). Lewinson’s book was the first formal guide to records pertaining to black history.

3. Ira Berlin, Leslie Rowland, and Joseph P. Reidy, eds., The Black Military Experience, Series II (Cambridge University Press, 1982), was the first volume published. Three subsequent volumes have been produced with different associate editors: Barbara Fields, Thavolia Glymph, Julie Saville, and Steven Miller.

4. For African American history in particular, see for example, the special summer 1997 issue of Prologue, which was devoted to African American historical research in NARA. The entire issue is on NARA’s web site at https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/summer_1997_table_of_contents.html. I also highly recommend Debra Newman Ham, “Government Documents,” in Evelyn Brooks-Higginbotham, Leon F. Litwack, Darlene Clark Hine, and Randall K. Burkett, eds., The Harvard Guide to African American History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001). Ham was formerly the Afro-American history specialist at the National Archives. Before she departed in 1986, she completed Black History: A Guide to Civilian Records. (National Archives Trust Fund, 1985); see also Jr., “Living With the Hydra: The Documentation of Slavery and the International Slave Trade in Federal Records,” Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives 32:4 (winter 2000). A database that identifies records that pertain to slavery and the international slave trade can be found at https://www.archives.gov/research_room/research_topics/slavery_records.html.

5. According to the National Research Council’s Doctorate Recipients from United States Universities: Summary Report 2000, the field of U.S. history generated the largest number of history PhDs over the past few decades. In 1999–2000, for instance, more than half of the PhDs produced (505 of 942) were in U.S. history, predominantly in 20th-century U.S. history. Maryellen Trautman, Government Document Specialist, NARA, assisted me in locating the report on the Web.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.