I love the movies, so choosing just one or two to write about is not an easy task. I could categorize the hundreds I have seen over my lifetime any number of ways—for example, favorite films that relate to my work as a historian of the U. S. South. Instead, I decided to consider movies that had a deeply emotional impact on me the first time I saw them. Two productions came immediately to mind, and I began to sort out the reasons why I found them so compelling.

I love the movies, so choosing just one or two to write about is not an easy task. I could categorize the hundreds I have seen over my lifetime any number of ways—for example, favorite films that relate to my work as a historian of the U. S. South. Instead, I decided to consider movies that had a deeply emotional impact on me the first time I saw them. Two productions came immediately to mind, and I began to sort out the reasons why I found them so compelling.

How Green Was My Valley was released in 1941, and Billy Elliot nearly 60 years later. Both are set in a particular time and place—How Green in a village in South Wales in the early 20th century, and Billy in a town in Durham County in northeastern England in 1984–85. Both feature a failed coal miners’ strike, and although I teach and write about labor history, that is not the main reason why I chose these films. Rather, I appreciated the poignant (and deliciously melodramatic) way each dealt with the themes of growing up in, and then leaving, a small town.

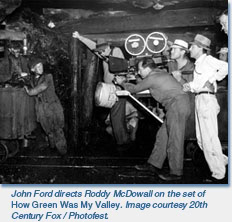

I first watched How Green on television at home, probably in the late 1950s or early 1960s. But I remember the day of the week and the time of day precisely. It was an early Sunday afternoon, and I was waiting for my cousins to arrive at my grandmother’s house, next door, for their weekly visit. The movie is based on the 1939 novel by Richard Llewellyn of the same name. It tells the story of the Morgan family—mother, father, six sons and daughter—with the story narrated by the youngest son, Huw (played by newcomer Roddy McDowall). At the beginning of the film Huw is an old man packing his belongings in the cloak of his deceased mother, preparing to leave the village where he has lived his whole life.

Directed by John Ford, the movie was shot in intense black and white; it has finely drawn characters and no happy ending. Of his family Huw says, “Coal miners were my father and all my brothers, and proud of their trade.” The scream of the mine whistle, the black coal dust that coats the men as they emerge from the mines, the bleak brick cottages, and the snow-covered surfaces of a hard winter, all evoke life in the village during the last years of Victoria’s reign. The film follows several narrative arcs. A new, enlightened clergyman arrives in town; although he and Huw’s sister fall in love, he fears he would not be able to support her adequately, and so stands by as she enters into a loveless marriage with the arrogant son of a wealthy mine owner. Iron workers from a nearby town flood into the village; displaced from their own jobs, they are willing to work for less than the current miners, and wages are slashed. Huw’s brothers support the union, and a bitter (and ultimately unsuccessful) strike stretches through winter.

One son dies in a mine accident, and, realizing that there is not enough work for all, two sons leave the valley for America. Two other sons are fired and replaced by desperate workers who will accept starvation wages. Huw’s father urges him to attend school and study to become a lawyer or doctor, but he decides to go into the mines and thus uphold a family tradition. In the movie’s most harrowing scene, Huw attempts to rescue his father after a mine explosion; the old man dies crushed by fallen timbers, half-submerged in water.

When I first saw this movie I was living in my hometown, a small crossroads in Delaware with only a few hundred people. My father had a middle-level white-collar job, so the struggles of coal miners seemed remote to me. On the other hand, I did feel immediate connections to the story. My father assured us that our Jones forbears did indeed come from Wales (though I have been able to trace his father’s line only back to 18th-century Pennsylvania.). And at the local elementary school I attended, I became friends with the sons and daughters of coal miners, recent migrants from West Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee, who had come to northern Delaware to find work in the General Motors and Chrysler auto assembly plants.

More generally, even at a young age I was developing a fascination with the way social differences cut across even the smallest of towns—the inevitable class, age, religious, political, and gender tensions that belied the image of any village as an idyllic, uncorrupted, and egalitarian place. In fact, my town had its own share of drama and unhappiness—the rivalry between church groups, the pervasive and destructive gossip, the class and generational tensions, the political differences, the rigid segregation of blacks and whites into separate schools and churches.

How Green Was My Valley is in some respects a declension narrative; Huw’s fond memories of his early childhood give way to sorrow over losses in labor and love. By the end of the film, slag heaps have overrun the verdant valley. I think that with its strong pro-union message, and its skeptical view of organized religion (the local deacon is particularly mean-spirited and rigid), this movie is remarkable in its own way. And it edged out Citizen Kane for the Academy Award for best movie in 1941.

I saw Billy Elliot in a movie theatre soon after it was released in 2000. Set in the fictional town of Everington, Durham County, England, this film too is told from the point of view of a boy, and he too is the son of a coal miner. Eleven-year old Billy (newcomer Jamie Bell) loves to dance—when he moves it’s like “’lectricity” running through his body, he says. His father is appalled when Billy shows an affinity for ballet shoes over boxing gloves: “Not for lads, Billy,” he says. “Lads do football or boxing or wrestling but not friggin ballet.”

I saw Billy Elliot in a movie theatre soon after it was released in 2000. Set in the fictional town of Everington, Durham County, England, this film too is told from the point of view of a boy, and he too is the son of a coal miner. Eleven-year old Billy (newcomer Jamie Bell) loves to dance—when he moves it’s like “’lectricity” running through his body, he says. His father is appalled when Billy shows an affinity for ballet shoes over boxing gloves: “Not for lads, Billy,” he says. “Lads do football or boxing or wrestling but not friggin ballet.”

Directed by Stephen Daldry, the movie reflects the events of the winter of 1984–85, when the Thatcher government sought to, and did, break the back of the National Union of Mineworkers by eliminating jobs in the coal industry in northern England and South Wales. Billy’s father and older brother Tony are committed union members, and among the most effectively choreographed scenes of the movie (in addition to Billy’s dance numbers) are the pitched battles between strikers and police. As the strike drags on, the town fractures. And by Christmastime, the family’s financial straits are so dire that the father chops up the beloved piano of his recently deceased wife to use as firewood.

The town’s ballet teacher recognizes Billy’s potential as a dancer, and, working with him in secret practice sessions, she prepares him for an audition with the Royal Ballet School in London. During a transformative moment, the father confronts Billy in a gym on a bitterly cold night, only to provoke in his son a newfound defiance expressed in an impromptu dance—a wild, exhilarating combination of step dancing, ballet, tap dance, and the Highland Fling. Now deciding that he wants to do right by the boy and to earn the money for his audition, the father boards a bus that transports scabs to the mine; in a heartbreaking scene, his older son dissuades him from going to work, and together they manage to scrape together enough money to send Billy to London.

Billy goes off to ballet school with the blessing of his father, brother, and grandmother (herself a thwarted dancer in her youth). The viewer wonders what will become of one of his Everington friends, Michael, who is gay; the town would seem to hold no future for him (and in fact he later resurfaces in London). The movie’s penultimate scene shows father and son crowded with other workers in a mine elevator slowly descending into the shaft, the strike now broken; but that image is quickly replaced by a scene several years later, with both men riding an immense escalator up and into the elegant theatre where Billy is starring in what is presumably Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake, a contemporary version of the Russian classic.

I saw this movie with my widowed mother, who insisted on living almost her whole life in the small town where she (and I) grew up, and with my own daughters, who were getting ready to leave home themselves. I found this film too to be a moving meditation on the limits of small-town communities; in Billy, the strike has pitted not only the middle class against the working class, but miner against miner, father against son. Moreover, at the time I saw it I was aware of the possibility that in a few years my own daughters would choose to move far away from their parents, a possibility that has since come to pass, with one living two time zones, and the other five time zones, away.

I think then that both movies reveal in a particularly compelling way a theme that is nearly universal in modern life, and certainly in mine—the tension between growing up in an isolated, self-contained little community, and the eventual needing to leave and be rid of it.