From the spring of 2022 through the fall of 2023, the AHA’s Grants to Sustain and Advance the Work of Historical Organizations provided $2.5 million to support dozens of small history-related organizations adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. These grants, ranging from $12,000 to $75,000, funded short-term projects that explored new ideas or built on experiments initiated during the pandemic—from developing virtual programming and online publications to using new technologies and expanding audiences and accessibility.

With AHA SHARP grants, small history organizations completed ambitious projects that required new thinking, new technologies, and new collaborations. Josh Calabrese/Unsplash

The AHA encouraged proposals for ambitious new initiatives as well as smaller projects that addressed problems that had arisen because of the pandemic. Funded through the National Endowment for the Humanities’ Sustaining the Humanities through the American Rescue Plan (SHARP) program, the AHA’s grants supported 50 organizations, including membership associations, site-based institutions, and history departments at historically Black colleges and universities.

Many of the grantees had not previously received federal funding, and the AHA’s subaward program made this funding more accessible to them. Organizations that might have lacked the resources or knowledge to apply for a grant directly from the federal government found the AHA’s program less daunting. With this smaller granting program, the AHA was able to devote significant time and effort to helping our awardees better understand requirements and compliance expectations of federal grants. And through our networks, we were able to reach organizations that were not previously aware of funding opportunities.

A full list of subrecipients and their projects can be found on the AHA website. Awardees included a wide range of organizations from across the country, including three archives, six cultural organizations, 11 historical societies, 11 membership organizations, 15 historic sites and museums, three affiliates in higher education, and one media organization. Most awardees implemented new programs or sustained existing ones, and several were able to create new positions with the funding, allowing for apprentices and researchers, for example. A few subrecipients used the funds to support general operations (like marketing and communications efforts) at their organization.

The projects funded through the program varied widely. They included oral histories; digitization projects to make collections more accessible; the development of resources and classroom materials; events and conferences; exhibits, programming, and tours; communications and marketing efforts to expand audiences; and internship/apprenticeship programs.

In April 2022, the AHA helped to coordinate the awardees’ marketing efforts to announce their grants and promote their projects. That month, we also held an orientation webinar, which included breakout sessions for attendees to make connections with others developing similar projects and share resources and expertise.

Throughout the grant period, grantees remained in contact with both the AHA and one another through email, during one-on-one Zoom meetings, and on a community listserv. A highlight of our SHARP grants program included regular Communities of Practice online sessions, during which grantees met to network, discuss common issues, and share resources. These regular meetings included presentations by content and methodology specialists on general topics, breakout sessions, and dedicated time for discussion among participants. These meetings were essential for attendees not only to learn from experts in their field but, equally important, to learn from one another and their shared experiences. Each attendee brought expertise, insights, and resources from their respective institution, which were valuable to others in attendance. Take, for example, the use of oral histories underpinning many of the participating organizations’ exhibits and projects. Participants with more experience in this methodology assisted others who were just beginning the process. These facilitated discussions enabled participants to build a community of peers from across the country and a network of resources accessible long after the program ended. (These connections even continued in person at the SHARP Grantees Meet-Up at the 2023 AHA annual meeting in Philadelphia!)

By the close of the SHARP grants program in August 2023, all awardees had completed their projects without major deviations from their original proposals. Some had faced staffing challenges or unexpected expenses (including a flood at one property!), but all were able to reach their project goals. The AHA’s own goal for the program was to encourage long-term connections that both identify and respond to the needs of organizations that are essential to the work of historians but often too small to take risks, or lack the resources to implement the creativity of their staff and volunteers. The program helped to foster these organizational relationships and contributed to the centrality of historical work in communities across the country.

As a result of the pandemic, the history-focused organizations receiving subawards through our program had faced disruptions to normal activities, including gatherings, services, or educational activities, and financial stringencies that led to layoffs and a decline in support for discretionary expenditures. The AHA’s SHARP grants not only enabled these organizations to address financial and operational issues caused by the pandemic but also created opportunities to rethink programming, identify new audiences, and experiment with ways to extend the work of humanities organizations in different directions.

Below, three historians share some of the varied experiences of the AHA’s SHARP grants recipients and represent the essential work of historians in museums, historical sites, higher education, and membership associations. From the development of an online exhibition about a community in rural Maine using GIS technology to the creation of a new museum about the history of incarceration and the establishment of a mentorship program for graduate students, the SHARP grants program had a deep and lasting impact on local communities and historians across the country.

Dana Schaffer is deputy director of the AHA.

MAPPING THE DENNYS RIVER THROUGH TIME

On a hot July weekend in 2021, a dozen college students ventured out along the Dennys River in Down East Maine to map its history. With portable GPS units strapped to their backs and accompanied by local guides, they trekked roads, fields, and streams, pointing their receivers skyward at passing satellites to mark sites of historical significance. They recorded the locations of tribal villages, local landmarks, and places of agricultural, domestic, civic, commercial, and environmental importance. By visiting these sites, the students were helping to create a picture of the communities that have been sustained by this corridor to the Atlantic across nine millennia to the present.

These students’ travels along the river were part of a project to investigate an important question: How does a small historical organization harness digital technology to tell its story? Since its founding in 1987, the Dennys River Historical Society (DRHS) has pursued a mission to discover, preserve, and share the history of this 123-square-mile watershed in eastern Maine. Yet as with many other such organizations, the advent of COVID-19 in 2020 created unforeseen challenges: public programming ceased, tours were canceled, the society’s Facebook page became locked and unusable, and membership froze. The pandemic halted the society’s popular summer expeditions, changing exhibitions, and regular lecture and discussion forums.

The DRHS recognized in the AHA’s SHARP grants program the opportunity to create an online presence that could revitalize the society, enabling it to emerge from the pandemic stronger than before. With a proposal entitled “Mapping the Dennys River over 9,000 Years,” we requested funding for a new website featuring an interactive map incorporating items from the society’s collections.

A year of intense activity included cartography and photography, as well as cataloging images to support the maps and writing accompanying text. The resulting website, dennysriverhistory.org, provides access to a growing collections catalog, information about the society, and seven iterations of a digital map that displays images and information about the communities in the watershed over the past 9,000 years. On a new Facebook page, a volunteer regularly posts images from the map that link to descriptive entries on the website for more details.

The project required collaboration with individuals and groups including the geographic information systems (GIS) program at the University of Maine at Machias (UMM), the Passamaquoddy Tribe, and the Tides Institute and Museum of Art in nearby Eastport. While the grant paid for a local web-design business to create the website, volunteers also donated hundreds of hours of their time, requiring significant coordination among the project partners.

In addition to society staff, participants included historian James Oberly (University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire, emeritus), Passamaquoddy tribal preservation officer Donald Soctomah, archivist Louise Merriam, geographer Tora Johnson (UMM), glaciologist Dominic Winski (Univ. of Maine, Orono), data scientist and intern Patricia Tilton, web designer Ashley Dhakal, and numerous volunteers. With such varied expertise and backgrounds, the team had to address differences in understanding and perspective among its members. For example, we recognized that when geographers track changes in place, historians study changes over time. The varied approaches taken by academic historians and local historians also came into play; where academic historians tend to work alone, usually thinking in time periods such as decades or centuries, local historians, by contrast, often reflect on personal connections to a specific place and time.

Our historians needed to become familiar with ArcGIS, a powerful mapping program used often by geographers.

Critical to the success of the project was learning to use software and technology new to the DRHS. Our historians needed to become familiar with ArcGIS, a powerful mapping program used often by geographers. Johnson, who heads UMM’s GIS program, helped the team to acquire a basic understanding of story maps, which became central to the interactive web map. To guide her students, Johnson asked the society to create a spreadsheet listing the names and locations of the sites and provide volunteers to guide them to those locations in the field. Following the initial fieldwork, the data was returned to the lab to be cleaned and assembled. Multiple sets of latitude and longitude coordinates had to be rectified, and ID numbers hastily assigned in the field needed to be compared and unified. Johnson created a mobile app for use with ArcGIS to allow Tilton and me to return to the field and fill in missing data. A patient investment of hundreds of hours resulted in data collection for over 450 historical sites.

Along with the ArcGIS technology, the society needed to create a digital repository to link its archives to the spreadsheet behind the interactive map. Using CatalogIt, a scalable, flexible, and accessible software, the archival staff could include images and documentation for each location. When the volume of historical information threatened to overwhelm the pop-ups on the interactive map, a “Learn More” link to the catalog record on the DRHS website helped solve the problem.

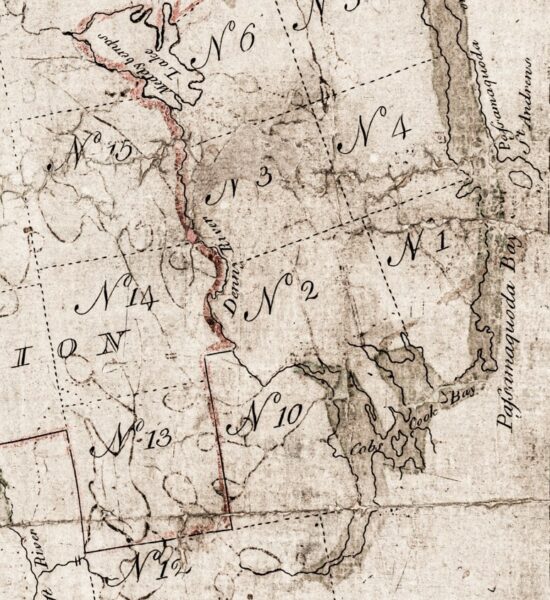

The Dennys River is shown on a Lottery Map prepared by the Massachusetts Committee for the Sale of Eastern Lands in 1786. Courtesy Dennys River Historical Society

Describing sites spanning multiple eras also proved challenging. A limitation inherent in the ArcGIS story map format is the restriction of using only one icon or symbol for each location across the chronological layers. For example, an early Passamaquoddy village at the head of the Dennys River subsequently became a mill site, then a potato field; by the 1940s, it had become the location of an electric power dam, then a junkyard, the location of a fish ladder, and an environmental cleanup site, before being returned to the tribe in 2021. Marking these locations separately, even though they overlapped, offered the best solution to a visually confusing situation. On the other end of the river, within one century the Dennysville Lumber Company’s mill building was relocated to serve variously as a Gulf Oil distributorship, a chicken hatchery, and a community center, before becoming a private art gallery in the 21st century. In this case, the society chose to feature the original and most recent uses of this building, while including further documentation in the catalog record.

The completion of this AHA-funded project has opened a host of possibilities for the future development of the DRHS, including expanded community engagement and education. Our project partners have suggested new directions in public programming such as the decline and reinvention of communities along the watershed, comparative studies on the reasons for in- and out-migration, and the interrelation of economic and environmental change. Users have already begun using the new website and the maps; their reviews have included requests for new search functions that will make the maps even more useful.

The project has greatly increased the depth and scope of the society’s research by providing a comprehensive historical vision of the area, extending our reach to new audiences online. As DRHS president Ron Windhorst has observed, this may not be classed as one of the great rivers of the world, but “Discovering the Dennys: A River through Time” ensures it will be in good company.

Colin Windhorst is program director at the Dennys River Historical Society.

EXPANDING THE NARRATIVE OF THE SING SING PRISON

Every chapter in America’s criminal justice history contains a few pages written at Sing Sing Prison “up the river” in Ossining, New York.

In May 2023, I hosted an unusual meeting of stakeholders at the Sing Sing Prison Museum offices. We invited five formerly incarcerated men, the former state commissioner of corrections, a retired corrections officer, a high school history teacher, a college professor, a prison reform activist, and museum staff to explore the museum’s future direction. This was the culminating event in a yearlong program funded by an AHA SHARP grant. Our goal was to update and expand the museum’s interpretive plan with a special emphasis on the impact of racialized mass incarceration since 1970. As we prepare to open the museum in 2025, the grant and the meeting in Ossining were significant turning points in shaping our path to the future.

The proposal to build a museum at Sing Sing originated in the late 1980s but lacked financial and political support. In 2015, new project leadership asked me to organize and manage a planning process and to develop an independent nonprofit organization that would work cooperatively with Sing Sing Correctional Facility, a maximum security prison with a population of around 1,500. By 2019, my role as consultant evolved into the museum’s part-time executive director. With the support of a board of trustees, and a small staff consisting of a full-time assistant director and four part-time collections and program employees, including two formerly incarcerated individuals, our mission focuses on sharing stories of incarceration and reform past and present and bringing people together to imagine and create a more just society.

Sing Sing Prison has been in operation for nearly 200 years. Located on the Hudson River about 35 miles north of New York City, the original site once held 1,200 men and became the symbol of the Auburn prison system based on solitude, silence, surveillance, congregate labor, and corporal punishment. The Mt. Pleasant State Prison for Women at Sing Sing (1839–77) was the first building constructed as a women’s prison in the country. Sing Sing became a site of capital punishment, with 614 executions in the electric chair between 1891 and 1963, including Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in 1953. But Sing Sing also was a place of innovative reforms. In 1914, the Mutual Welfare League, a form of self-government created by prison reformer Thomas Mott Osborne, was founded there. Lewis Lawes, warden from 1920 to 1941, introduced modern penology and became the nation’s most respected prison official. Today, private sector support organizations such as the Osborne Association, Hudson Link for Higher Education in Prison, and Rehabilitation through the Arts provide valuable programs for men preparing to reenter society after leaving prison.

The rise of racialized mass incarceration since 1970 marks a distinct and singular chapter in Sing Sing’s history. To document this story, we commissioned a report from historian Logan McBride (Macaulay Honors Coll., City Univ. of New York), who has written about Black correction officers in the New York State prison system during the 1960s and 1970s. Her report traces the origins of mass incarceration in New York, starting with Governor Nelson Rockefeller’s reorganization of the state’s criminal legal system in October 1970, the deadly uprising at Attica State Prison in 1971, and the dramatic growth of the incarcerated population in New York and across the nation through the late 20th century. McBride’s report also explores the increase of women in prison, the impact of the AIDS and COVID epidemics, and the portrayal of prison life in popular culture.

We were redefining our identity as a prison museum.

The May 2023 stakeholders meeting used the McBride report as a catalyst for challenging common assumptions about mass incarceration. After three hours of intense and candid conversation, we identified three key messages. First, leadership matters. Former superintendent Brian Fischer explained how he had expanded the work of education, rehabilitation, and faith-based organizations during his tenure from 2000 to 2007. Of equal importance, he was receptive to program ideas from the prison population and conveyed a sense of genuine trust and respect. Second, diversity matters. By the 1990s, Sing Sing’s workforce became the most diverse in the New York state system. The presence of Black and Latinx correction officers and support staff—who often came from the same neighborhoods as the incarcerated population—contributed to better communications and reduced the potential of racial conflict. Finally, support networks matter. Despite—or perhaps because of—the trauma of incarceration, the formerly incarcerated men emphasized the importance of informal networks of mutual aid inside prison that offer support during the long periods of isolation from family and friends. These bonds of friendship are essential in preparing for the day when they come home. For the museum, the stakeholders recommended a visitor experience that revealed the humanity of incarcerated individuals as well as the barriers to changing a rigid system. They stressed that the museum’s audience should include students and educators, families of incarcerated and formally incarcerated people, correctional facility staff, and members of faith-based communities.

In addition to the McBride report and the stakeholders meeting, the grant funded an online exhibition called Opening Windows. We contracted with Blue Telescope, an interactive exhibit company, to develop major content areas including an illustrated timeline, a justice statement, a visitor survey, and stories about people, places, and objects connected to Sing Sing Prison past and present. The exhibition enables the museum to expand online learning opportunities and audience engagement. Blue Telescope earned a prestigious MUSE gold award for the exhibition.

The grant was a catalyst for a transformative growth in the museum’s capacity to fulfill its mission. As we explored Sing Sing’s recent history, created new online content, and promoted partnerships with stakeholders, we realized that we were redefining our identity as a prison museum. The grant cycle of 2022–23 coincided with the development of a revised master plan and new mission and vision statements, the welcoming of new board members and staff, and the opening of a new office in downtown Ossining. We increased online and in-person public programs and participated in local, state, and national meetings. We also recorded oral history interviews with retired Sing Sing staff and maintained our commitment to amplify the diverse voices of people impacted by the justice system.

As we prepare to commemorate Sing Sing’s bicentennial in 2025, we face a number of strategic challenges. First, we must ensure that the privacy of the incarcerated population and the daily operations of the facility are not disrupted by tours and programs. Second, we must collaborate with a wide variety of partners including government agencies, cultural institutions, and reform organizations. Finally, we must create a platform contributing to the national conversation on criminal justice that recognizes the legacy of a brutal past but also makes visible the agents of change who are working to create a society that values individual humanity and dignity. As we concluded at the stakeholders meeting, Sing Sing was exceptional but not an exception. The museum must try to reconcile compelling and often contradictory narratives and call on history as a resource to help us understand our own times.

Brent D. Glass is director emeritus of the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution and president of Brent D. Glass LLC.

MENTORING REIMAGINED

Mentorship has long been at the heart of the Western Association of Women Historians (WAWH). Established in 1969 and designed to serve scholars in the 14 western states of the United States, the organization was founded by a cohort of historians who literally had to mentor themselves. These early members were often the only women in their graduate cohorts or history departments, so WAWH meetings provided critically important intellectual encouragement and social solidarity and tried to draw the map of professionalism where there was precious little to go on.

Mentorship was part of the WAWH’s DNA, but the COVID-19 pandemic tested our resilience. Our 2020 annual conference was canceled. We managed to meet fully online in 2021 (thank you, Ula Taylor!), but for more than two years, we missed that face-to-face connection that is so important to feeling truly connected and in community. Our leadership worried that our membership, especially graduate students and early career scholars, would suffer and, of course, feared for the integrity of our organization as well.

I was in touch with colleagues (mostly in California) who were recent veterans of transitioning teaching and research into the remote environment and eager to lend a hand. An unexpected partnership was born between the WAWH and the University of California Consortium for the Study of Women, Genders, and Sexualities in the Americas.

Not good at applying for grants? Me neither. The first lesson I learned was that I had colleagues who were experts and eager to help. The consortium had written a grant proposal to support a student-centered research project called the Empire Suffrage Syllabus to mark the 100th anniversary of the passage of the 19th Amendment. This project was a good model for WAWH, since our more than 50-year history is centered on mentorship, support, and professional development for early career scholars and graduate students. Without meeting in person at our annual conference, we could literally not fulfill our mission. The AHA SHARP grant and the partnership provided the opportunity for WAWH to think in fresh ways about our mentorship mission, pushed as we were so forcefully into the digital environment.

The second lesson I learned was that mentorship could—or perhaps needed to—work in the online environment. Up-and-coming historians were already more wired into the digital world than I was, so the time was now to show up and meet them there. The WAWH and the consortium leadership together devised a series of online workshops to be held over Zoom to try to meet our constituents where they already were.

The project was an investment in the next generation of historians.

Like many other organizations during the pandemic, we had to make a compelling case about why these scholars should spend time with us. We framed the project as an investment in the next generation of historians, and in fact, the majority of the grant funding provided stipends for participants. We wanted our members to know that they are valued, their time is valued, and their work is valued. Compensating participants for their time sent a very clear message about this value. We also compensated our convening faculty.

To get buy-in from potential participants, we surveyed our membership early and often. Their responses confirmed an interest in and need for connecting with senior scholars in informal, lower-risk intellectual environments. Based on survey feedback, we devised a yearlong schedule of monthly sessions on topics suggested by our membership. We also planned a one-day in-person workshop at Portland State University. Through a flurry of emails and Google Forms, we signed up six yearlong participants for the monthly mentor sessions and six workshop participants who would take a deep dive into the digital humanities led by experts.

We sent out a general invitation to our membership, but those who came forward to participate had two things in common. First, they were mostly graduate students, most in the predissertation phase. Second, they had advisors who strongly encouraged them to participate. The organizers thought that the stipend would send a strong and attractive message—and it did—but money was not enough to secure a commitment from very busy historians in training. Turns out, the encouragement and validation provided by their supervising faculty proved quite decisive. This lesson was an important one for our thinking about mentorship in WAWH.

Each month, participants and convening faculty met for two hours on Zoom in sessions that toggled between issues in professionalism (such as work-family balance and diversity, equity, and inclusion) and writing workshops. The issue-based discussions were engaging, especially as people were starting to get to know each other in the earliest sessions. However, the writing workshops were the strongest sessions. This was another lesson learned: graduate students need rigorous, nonjudgmental, and collaborative ways to work on their writing. WAWH’s membership comprises a cadre of highly skilled teachers of writing and people with considerable chops in professional development work. From my vantage point as the support person for all the Zoom sessions, it was eye-opening and inspiring to see colleagues skillfully manage a writing workshop in caring and deeply insightful ways. The feedback from participants underscored the powerful connection made. One wrote, “The activity of free writing from the perspective of a character in my project transformed how I think about the art of narrating. I also genuinely appreciated the structure of today’s writing session; it was very organized and productive use of time.” Another reported, “Today’s session equipped me with tangible tools and resources for tackling ‘writer’s block.’” A third recognized how they would return to the day’s lessons, saying, “For the size of our group and the time frame we had for the session, this was a great balance of writing exercise and discussion/debriefing. I even kept a copy of the exercises to refer back to when I (inevitably) get stuck in my writing down the line.”

Yet the digital training workshop reminded us of the still irreplaceable role of in-person connection. On that day in Portland, we benefited from expert guidance from two outstanding practitioners of digital humanities. Ashley Garcia (Univ. of California, Los Angeles) provided a generous overview of the field and opportunities for participants to try new platforms and programs and have their questions answered in real time. Jeanette Jones (Univ. of Nebraska–Lincoln) guided participants through a major completed digital project, her To Enter Africa from America: The United States, Africa, and the New Imperialism, 1862–1919. The group then shared a home-cooked dinner together along with women historians from Portland State and the community.

We anticipate two long-term impacts of the program. One is to continue to engage with the program participants, be there for them across their careers, and support their links with one another. WAWH also plans to invest more pointedly in its own mentorship capacity, including writing future grant proposals and doing targeted fundraising. In the near future, we expect to add a new position on our board, something like a mentorship chair, to spearhead these efforts.

I spent time with several participants during the Berkshire Conference in June 2023 and was told things like “I would have never been able to complete my PhD prospectus without the mentorship program” and “Meeting with that group all year gave me a connection that I didn’t know I needed at this stage of my career.” I could not have asked for a more rewarding exchange with these wonderful young scholars.

Patricia Schechter is professor of history at Portland State University and immediate past president of the Western Association of Women Historians.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.