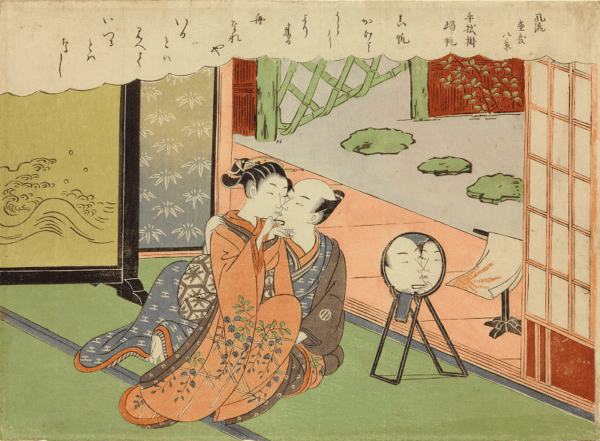

Suzuki Harunobu’s 1768 Tenugui-kake kihan (Returning Sail at the Towel Rack) shows lovers embracing. Wikimedia Commons

At the University of Massachusetts Amherst, we have a range of courses on the history of women, gender, and sexuality. These are aimed at upper-division students and don’t follow seamlessly from the introductory US or world history surveys. To develop a curricular track in the history of women, gender, and sexuality, we needed to take the history of sex to first-year students. With support from a Mellon Mutual Mentoring Grant, Julio Capó Jr., Priyanka Srivastava, and I decided to launch a survey course on the global history of sex that would take its place alongside the US and world history surveys already offered by the history department at the university.

Given our geographic specializations in the histories of the United States, Latin America, and South Asia, a course on the global history of sex seemed like a natural point of intersection that could also serve as a point of departure for a broad range of upper-division courses on the histories of women, sexuality, and gender. We deliberately framed the course as the history of sex because students often assume that courses on the history of sexuality focus on LGBTQIA history. We wanted to signal a more expansive course that would include the history of sexuality but would also contextualize sex, gender, and sexuality together. As the senior member of our group, I volunteered to pilot the course.

Because I could not assume students had any prior history experience, I decided to integrate the major events, trends, personalities, and institutions in world history with those of the histories of gender, sex, and sexuality. I focused on episodes where sex, gender, and sexuality illuminated major features of global history. As might be expected, there is no textbook that covers four centuries of global history from the perspective of sex, gender, and sexuality. While there are great secondary sources, finding appropriate primary sources that have been translated into English presented a further challenge. More important, though, was the task of finding themes that would pull together everything in world history and the histories of sex, gender, and sexuality. Fortunately, Robert M. Buffington, Eithne Luibhéid, and Donna J. Guy’s A Global History of Sexuality: The Modern Era (2014) offered an excellent set of essays that placed key issues in the history of sexuality within a world history framework. This became the course’s central text, and the themes of representation, colonialism, and rights and regulations bound together material from the Spanish conquest of the Americas to contemporary transgender history.

As I assembled images and material into PowerPoint lecture slides, I ran up against another challenge: some of the material I wanted to present was sexually explicit. How were students going to react to a screen filled with Edo-era Japanese erotica or other graphic images? I know that this is the age of the Internet, but Massachusetts still has 19th-century obscenity and lewdness laws on the books. The only advice our ombuds office could offer was to ask everyone to bring an ID and prove that they were over 18 on the first day of class. What worked better was that as a class, we created a set of ground rules for how best to foster a respectful learning experience. For many of my students, the topic of the global history of sex was fascinating, but the prospect of saying something that could cause offense or that might just seem naïve was daunting. As a result, students articulated a principle of tolerance that would allow them to ask questions without risk of offense or judgment; in their words, “Don’t assume malice, and don’t generate malice.” They recognized that some topics might be triggering and that pronouns shouldn’t be assumed, but they wanted everyone to stay engaged and continue to communicate.

Some of the material I wanted to present was sexually explicit. How were students going to react to a screen filled with Edo-era Japanese erotica or other graphic images?

As far as I could tell, students were less shocked by the sexual content in the course than by the policies and practices of governments and societies. Many students were genuinely surprised to learn how governments used laws and norms about sex and sexuality to regulate the behavior of their citizens. The intrusion of the state into the bedroom was often clearest in colonial contexts, but tracing the influence of these measures into the modern era was something new for students, who made assumptions based on their experiences about privacy, birth control, and the role of the state in the reproduction of its citizenry.

For a generation of students inundated with sex online and in the media, it was gratifying to offer global and historical perspectives on topics from sex workers to sexual fluidity. But, as I’ve discovered in the past, students’ understanding of contemporary issues is often as uneven as their understanding of the past. For example, in my US women’s history courses, I used to bring in Bill Baird, a pioneer in the reproductive rights movement, to discuss his fight for legalized birth control in the United States. As he gave his pitch about contraception—the same one he had used in the 1960s—I realized that we could not assume that our students had an accurate understanding of contemporary reproductive biology. Even though sex education is required in high school, the quality of instruction varies and is often incomplete or misleading when it comes to conception and birth control. So, for the course on the history of sex, I invited a biologist to guide us through the current scientific nuances regarding human reproduction. Science students loved this lecture, but others found it too distant from the historical trajectory we had been developing. In the future, I will find ways to better contextualize contemporary biological material, perhaps as a class on the history of sex education itself.

As you might expect, a course on the history of sex was popular among college students and quickly filled to its capacity of 58 students. While the course was designed as an introductory history survey with first-year students in mind, over half of the students were juniors and seniors, and only two were in their first year. In addition, only two students had declared majors in history. The rest had majors ranging from microbiology to finance, from sustainable food and farming to communication disorders. Most students probably enrolled to fulfill a general education requirement with a class that they thought would be fun. By and large, they weren’t disappointed. Putting aside requests to cover less material, their evaluations at the end of the term were positive. Significantly, many said that they were interested in taking more history courses. Time will tell if they do, but for now our experiment in integrating world history with the histories of sex, gender, and sexuality has been successful enough to increase the enrollment cap for its next offering.

Laura L. Lovett is an associate professor of history at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. A specialist in US women’s history and the history of childhood and youth, she is the author of Conceiving the Future: Pronatalism, Reproduction, and the Family in the United States, 1890–1930 and a founding coeditor of the Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth. She is currently writing a biography of African American activist Dorothy Pitman Hughes.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.