When peaceful civil rights marchers were brutally beaten in Selma, Alabama, in 1965, the world reacted with horror at the photographs appearing in newspapers across the globe. The international response to Selma, which shows the global reach of the civil rights movement and the international following achieved by leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., is not featured in the filmSelma. But as Leslie Harris writes in this series, “the artist’s vision is different” than the historian’s. I might have wished for a broader narrative frame to show the international aspects of this story, but no film could capture the complexity of history.

My contribution to this series is less about the film itself than about one of the stories it left out: the role of Selma in the broader international history of American civil rights. Though worldwide attention had long been paid to race relations in the United States, foreign reaction to Selma was different than during previous civil rights crises. By the late 1940s, the impact of American racism on the nation’s global image, and on US Cold War foreign relations, was of great concern to American diplomats and political leaders, and civil rights activists used this as one of their arguments about the need for social change. But the impact of civil rights on the American image abroad was not static. It changed over time—not only because the underlying story changed, but because the government went to great effort to turn the international understanding of American racism into a story about the benefits of democracy over communism.

The Soviet Union had used race as a principal anti-American propaganda theme since the late 1940s, but the most important source of global criticism of the United States was straightforward news about events that actually happened. Initially, the US responded with its own propaganda: pointing to segregated schools and colleges, for instance, as evidence that African Americans had educational opportunities. But it became clear that more had to be done to change foreign perceptions.

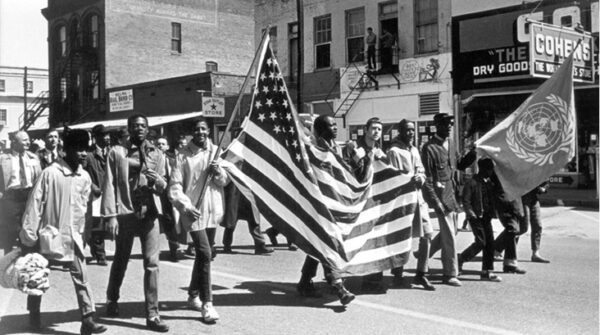

The March to Montgomery, 1965. Photo by John Kouns on Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement website (www.crmvet.org).

By the mid-1950s, every civil rights crisis at home generated a diplomatic reaction, and great effort was put into managing foreign opinion. Secretaries of State sent out talking points to American embassies around the world, arguing that the federal government supported civil rights; that abuses were the result of rogue elements in particular states; that the nation had evolved from slavery to freedom; and that this progress illustrated what democracy as a system of government could accomplish. Even great brutality, like the abuse of demonstrators in Birmingham, Alabama, in May 1963, was presented as an aberration in the seemingly inevitable march toward equality.

The turning point in this story came in 1963 and 1964. In the aftermath of widespread national and international criticism of police brutality in Birmingham, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Analysts from within the State Department and the United States Information Agency (USIA) believed that peoples of other nations were coming around to the view long promoted: that the US government supported civil rights, and that continuing discrimination was not the fault of the federal government nor evidence of a weakness in democracy itself.

_fmt-600x379.jpg)

Credit: Peter Pettus. 1965. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Lot 13514, no. 25.

Civil rights marchers with flags walk from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, in 1965.

Then came Selma. In earlier years, such brutality would have meant a setback in the effort to protect the country’s image internationally. Not so in 1965. Global news coverage of Selma was less critical than expected. The USIA reported that “world press comment on Selma has been more calm and restrained than the treatment accorded earlier US racial conflicts.” In spite of widespread coverage of police brutality, editorials on Selma “have expressed increasing understanding.” Due to President Johnson’s call for Congress to pass a Voting Rights Act, the international press saw “little room for doubt that the Negro American is winning his struggle with the strong support of the Federal Government and the great majority of the American people.” Even in the Soviet Union, coverage of Selma was limited, though Chinese propaganda depicted the Voting Rights Act as designed only to “paralyze the fighting will of the Negroes.”

American inequality persisted, but international opinion had turned around. Formal legal change, advertised to the world in glossy pamphlets and described to foreign audiences by government-funded speakers, had made an impact. Selma came at a time when international attention was shifting not only because of the government’s marketing campaign, but also because another American development had become the focus of global interest. Selma coverage often appeared on the inside pages of the world’s newspapers, sometimes displaced by front-page coverage of the war in Vietnam.

The film Selma was not written to capture this story. What it might have done without detracting from its powerful human narrative was dramatize the way Selma implicated the very meaning of American democracy. When marchers proceeded from Selma into Montgomery, they literally wrapped themselves in American flags. With stars and stripes carried or painted on faces, they reclaimed and reinterpreted American meaning.

is an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University, and is the Asa Griggs Candler Professor of Law at Emory University. Her most recent book is War Time: An Idea, Its History, Its Consequences (2012). This essay draws from her first book, Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy (2000).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.