When I talk to French and German colleagues who belong to my generational cohort, I’m struck by the fact that retirement isn’t an obviously fraught subject for them. The rules governing their centralized state systems of higher education include a mandatory retirement age. Particular circumstances may extend it by a couple of years, but the basic principle holds for everyone. A given individual may or may not relish the idea of retirement, but no matter: he or she must accede to it. At the level of practice, then, if not necessarily at the psychological level, clarity and order reign. Retirement, the last stage of the professional life cycle of an academic, is simply a fact of life, an inevitability.

Not so in the United States, where a federal law of 1993 gave tenured professors freedom of choice about when and indeed whether to retire. Freedom of choice in the conduct of one’s life is an intrinsic good as well as a quintessentially American ideal. But in this case it comes with certain costs that deserve the attention of academic members of our discipline, the junior members as well as the senior. For the individual professor getting on in years, the burden of choice can produce a mutually reinforcing cycle of indecision and anxiety—one that is intensified by the relative lack of public conversation about retirement. For the collectivity, elimination of mandatory retirement contributes to the academic job crisis, keeping existing positions filled at a time when broader structural factors—the cutting of college and university budgets, the turn to part-time faculty employment at the expense of tenure-track jobs—have already made new openings painfully scarce. Retirement holds little meaning for young historians in search of their first tenure-track jobs, except insofar as many of them, rightly or wrongly, see the nonretirement of their elders as blocking their own professional futures.

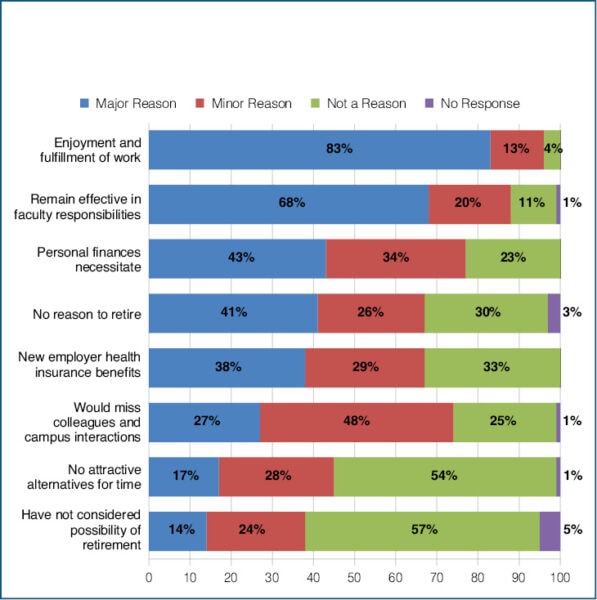

It’s widely assumed that the crash of 2008, which eroded the value of pension accounts, is largely responsible for the current reluctance on the part of many professors in the appropriate age bracket to retire. Such people simply cannot now afford to take retirement as early as they’d planned, this story goes. But a study sponsored by TIAA-CREF, carried out by the Chronicle of Higher Education and published in 2013, shows a very different picture.1 In its survey of faculty over the age of 60, the study found that a mere 15 percent were in fact eager to retire at “normal retirement age” (roughly 65 years old) but were prevented from doing so by adverse financial situations; moreover, only half of that group mentioned the aftereffects of 2008 as figuring into their calculations. At the other end of the spectrum, a full 90 percent of those surveyed expressed reluctance to retire at 65, and some 60 percent had made a firm choice to continue beyond that benchmark. The reasons for postponing retirement identified by this study were overwhelmingly positive: professors enjoy what they do. But darker emotions also routinely surfaced among those surveyed. Having a real passion for their work and a powerful identification with it, professors worry about the consequences of cutting themselves off voluntarily from a work environment so bound up with their sense of self.

Further data supplied by this same report confirm the hypothesis that delayed retirement is driven much less by material factors than existential ones. For example, faced with the planning dilemmas caused by uncertain retirement dates, many institutions have devised financial incentives to encourage timely decision -making and departure. But, contrary to expectation, such programs have everywhere met with quite limited success.

And finally there is anecdotal evidence. In an eloquent, candid, and wise essay she wrote for this magazine a couple of years ago, former AHA President Caroline Bynum recounted that “over the year in which I prepared for retirement, I found that the term . . . induced reactions of such astonishing anxiety and bitterness [among colleagues] that I became hesitant even to mention my plans.”2 A mere allusion to those plans, she concluded, was interpreted by her age-mates as a covert suggestion that they too should retire, and this imagined suggestion in turn generated patent “anxiety and bitterness.”

Perhaps most significantly for our purposes here, a repeated sequence of such events led Bynum to clam up about the evidently unspeakable subject. My own recent experience confirms that colleagues who are not close friends rarely talk to one another about retirement: when one passes the age of 60 it becomes a strangely tabooed topic. Perhaps in part because of this taboo, retirement can be felt as a stigma by those who choose it. I recall seeing, some months after he retired, an eminent and well-loved colleague in the corridor of a floor occupied by history faculty. Having, at that point in my life, little reason to think much about retirement, I was surprised to realize that his demeanor was vaguely embarrassed and apologetic, as if he’d been discovered in a place where he no longer belonged. I’d never imagined that retirement could have such an effect. This disturbing chance encounter was probably my first intimation that the last stage in the academic life cycle might be a threat, rather than the welcome reward for long service I had thought it to be.

Source: Survey of faculty members by TIAA-CREF Institute, cited in Jeffrey J. Selingo, “Aging Academe: Retirement Trends in Higher Education,” Chronicle of Higher Education, 2013.

Why do you expect to work past a normal retirement age?

Is there, then, anything to be done about the knot of problems, individual and collective, surrounding retirement? And, furthermore, is there anything to be done in which the AHA might have a role?

Caroline Bynum’s essay makes a persuasive case for retirement as reward. It details the opportunities retirement provides both for unfettered personal and intellectual growth (“re-tiring” as equipping one’s vehicle with new gear for the continued journey) and for unique and gratifying forms of service to one’s home institution and the larger profession. It situates the retiree, should he or she desire, in firm connection with the academic family. In general, it helps dispel the irrational terrors sometimes attached to the retired state. But while the essay might have initiated a public conversation among us, it has not been much followed up—an unfortunate outcome consistent with the taboo I’ve postulated. That retirement is an intensely personal matter doesn’t mean that it should be pondered only in solitude. I suspect that many if not most senior professors are ambivalent about which choice is right for them and would welcome some company in weighing the alternatives. The profession as a whole would be better served by more openness and public conversation about retirement as well as by more shared information about the various institutional forms being developed to respond to it. The AHA can provide a forum for those exchanges.

Even a cursory view of the retirement landscape reveals intriguing initiatives designed to respond to the existential needs of retirees. For example, some institutions (Yale, Hopkins, the University of Southern California) have established centers that bring emeritus faculty together for intellectual discussion, research presentations, and camaraderie.3 The American Sociological Association recently created the ASA Opportunities in Retirement Network, including a Listserv for all emeritus sociologists and those at or near retirement age.4 But there has been, to my knowledge, no effort to catalog such efforts or to brainstorm for new possibilities. Institutional and departmental practice with respect to retirees varies enormously and seems to be the result more of happenstance than of considered policy. While some desirable practices require material resources—e.g., providing offices or shared office space for retirees—others that do not are nonetheless often overlooked—e.g., keeping retirees on the department Listserv, inviting them to job talks, and otherwise encouraging their (nonvoting) participation in the life of the department.

I remember a colleague from another university talking at dinner in the early 1990s about her confidence that we baby boomers, who had spearheaded the entrance of women into the academy and pioneered new forms of family, would be equally creative when it came to retirement. I dimly recall her floating the idea of communal living arrangements for retired historians, which would keep us intellectually nimble and productive, and my agreeing that our generation would have the spunk and collective spirit to pull off something like that. While the particular utopia she suggested no longer appeals to me, the idea of a creative and collective response to retirement certainly does. It’s we historians, after all, who introduced the idea that the human life cycle was not entirely prescribed by nature but socially constructed, with stages like “childhood” and “adolescence” demarcated and theorized at the historical conjunctures that highlighted their particular relevance. The moment may have come for us to rethink “retirement.” Perhaps it could be reconceptualized as a problem of intergenerational solidarity, with the older generation recognizing the desirability of freeing up their positions for a younger generation whose professional futures are endangered and everyone recognizing the desirability of keeping retirees in the family. In any case, the AHA can provide a forum for that rethinking. Let the conversation begin.

Notes

- Jeffrey J. Selingo, “Aging Academe: Retirement Trends in Higher Education,” Chronicle of Higher Education, 2013. [↩]

- Caroline Walker Bynum, “Time to Retire?” Perspectives on History, December 2012. [↩]

- For the Yale model, see Henry Koerner Center for Emeritus Faculty; for the Hopkins model, see “About the Academy: Redefining Academic Retirement,” https://krieger2.jhu.edu/theacademy/about/; for the University of Southern California model, see “The Next Chapter: Well-being, Fulfillment and Joy,” https://emeriti.usc.edu/. [↩]

- “ASA’s New Opportunities in Retirement Network Formed,” Footnotes: A Publication of the American Sociological Association, April 2014, https://www.asanet.org/footnotes/apr14/orn_0414.html. [↩]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.