Over the past several months, student protests around the country have rocked higher education, taking up questions of racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination. Faculty and administrators at all kinds of institutions—small and large, public and private—must confront and respond to student demands for change.

Over the past several months, student protests around the country have rocked higher education, taking up questions of racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination. Faculty and administrators at all kinds of institutions—small and large, public and private—must confront and respond to student demands for change.

At this year’s AHA annual meeting in Atlanta, a special panel on student unrest, titled “From #ConcernedStudent1950 to Diversifying the Profession: Responding to Student Demands for Change,” brought together six professors and administrators of color—Matthew Garcia (Arizona State Univ.), Marcia Chatelain (Georgetown Univ.), Duchess Harris (Macalester Coll.), Jonathan Holloway (Yale Univ.), Douglas Haynes (Univ. of California, Irvine), and Jacquelyn Jones Royster (Georgia Tech)—to discuss the protests’ roots, consequences, and implications, as well as their relation to the ongoing conversation about faculty diversity. Although the panelists mostly represented R1 institutions, their insights seemed to resonate with the audience.

Garcia introduced the roundtable as a debate forum, but the panelists largely agreed on most points. They expressed sympathy for students’ grievances; reminded the audience that student agitation is nothing new—that it is, in fact, part of a long college tradition, even a rite of passage; suggested that faculty diversification is key to addressing student discontent; and reiterated that campus unrest cannot be considered in isolation from larger, systemic inequalities. In contrast to public commentary, seemingly mired in acrimony, the panel pushed debate forward by acknowledging the legitimate struggles and concerns that student protests have highlighted.

The panelists refused to criticize student movements and instead validated their concerns and efforts to illuminate problems that, as Harris noted, administrators have often recognized only begrudgingly. With “intolerable racism” persisting on campuses across the country, with sexual harassment and assault still a daily threat for students, and with graduate students losing their health care (at the University of Missouri, this happened with 14 hours’ notice), students are justified, the panelists agreed, in demanding change. As Garcia explained, these students are asking themselves, “Why are we submitting ourselves to this abuse?” while paying ever-increasing tuition or, in the case of graduate students, working more than ever with few benefits and even fewer job prospects.

In addition to mobilizing demonstrations, students from traditionally marginalized constituencies are often using social media to conduct outreach and promote their causes. The Twitter hashtag #ConcernedStudent1950 emerged at Missouri, for example, taking its name from the year the first African American student entered the university. Chatelain (herself an alumna of Mizzou) observed that platforms like Twitter and Instagram reach beyond single campuses and have permitted the creation of “a national community of students rethinking what they mean to these institutions.”

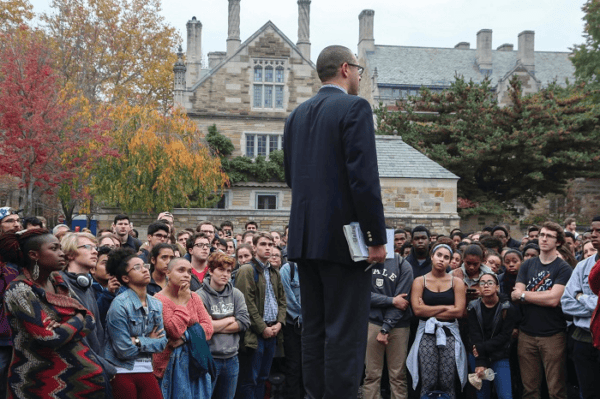

Student challenges to perceived injustices are nothing new. From the 1960 Greensboro sit-ins led by black students defying segregation to the California campus walkouts in objection to the state’s anti-immigrant Proposition 187 in 1994, college students have historically positioned themselves at the vanguard of social change. Today’s protests and responses, however, unfold much more publicly and visibly, thanks to social media. Holloway is well aware of this, having earned wide praise for his leadership at Yale last fall; tensions erupted there after concerns about potentially offensive Halloween costumes sparked broader discussions about racial climate, microaggressions, and free speech. These conversations evolved in part as a result of social media campaigns, which at times targeted professors and administrators whom students accused of being unresponsive or insensitive.

Students from traditionally marginalized constituencies are forming communities to empower themselves, often using social media.

As Holloway observed, “Our margin for error for saying the wrong thing is almost zero.” He candidly offered insights into how he responded to the “powerful and painful” demands of students, which he said reminded him of his own struggles and activism as a student. Listening was central to his handling of the situation, he said: “If I am not prepared to listen to students I should not be in this job, to be honest.” Promises to “do better” stood in stark contrast to some other administrators’ harsh and defensive responses, panelists noted (without naming specific people). While some administrators, faculty, and outside commentators have called protesters childish, immature, or politically correct, the panelists argued that these views are unfair, disingenuous, and ultimately unproductive. “I don’t accept that in any way,” said Chatelain, calling such reactions “a perfect mask” for inaction and shifting attention away from students’ legitimate demands.

Douglas, too, defended activists, observing that “students are trying to form a political interest” to counter “established” powers within higher education. Uneven power relations are bound to create frustrations for students, he stressed, which inevitably produce less than “civil” exchanges. Besides, he added, “[in]civility is a problematic charge because some of our faculty settings aren’t particularly civil, either.” Additionally, student political formations can appear alienating to faculty and administrators who sit somewhat removed from campus life. Like Chatelain, Holloway condemned administrators’ negative charges as “a complete smokescreen,” asserting that students’ political style is perfectly “age appropriate.” Royster added that administrators “have to be the adults in the room,” to respond to student demands with understanding and compassion instead of condescension.

As the title of the panel implied, however, the continuing lack of faculty diversity on college campuses remains a glaring problem in the profession, and it’s one of the institutional problems students most frequently cite. As the Chronicle of Higher Education demonstrated in a broad survey of higher education institutions across the country (published online October 12, 2015), less than half (44 percent) of full-time faculty members were women, even though female college students now outnumber men, and only 22 percent were minorities. The panelists made clear, in fact, that these issues naturally intertwine. How, panelists wondered, can students of color possibly feel valued if the faculty who teach and mentor them look nothing like them? Royster, perhaps most passionately, insisted that ignorance of these figures can no longer excuse inaction on faculty diversification: “We know this is a problem. We know it well.” Haynes similarly criticized the “constant critique of institutional bloating,” deeming it a euphemism for faculty diversification.

The problems, of course, are often institutional and systemic, as the panelists recognized. The lack of faculty diversity isn’t due to some nefarious, conscious, and deliberate attempt to keep minorities out of academia. But implicit bias, university corporatization, and adjunctification have marginalized qualified minority scholars, unable to find work despite the need for a more representative faculty. Hiring minority scholars to contingent positions at the same time as we witness the devaluation of the humanities arguably distorts how we perceive the discipline and its challenges. Perhaps, as some in attendance implied, students do care about history but are constantly urged to become disciplined workers rather than critical thinkers—or come to believe critical thinking isn’t important to employers.

Overall, the panelists seemed concerned but cautiously optimistic. Clearly, much work remains if faculty and administrators are to properly address student concerns about fairness, inclusion, and diversity. But Royster, who recounted frequently being mistaken for a maid, nonetheless argued that “faith in possibilities,” along with ongoing pressure from socially conscious students, scholars of traditionally marginalized communities, and their allies, might gradually produce a more harmonious, diverse, and dignified learning and working environment.

is a PhD student in American history at Duke University. You can follow him on Twitter @e_b_bobadilla.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.