After presenting a paper at the Organization of American Historians (OAH) annual meeting, I was approached by the individuals overseeing the collaboration between the OAH and the National Park Service (NPS) to consider working on a historic resource study. Historic resource studies are valuable reports that offer historical overviews and assess all cultural resources and assets within the boundaries of a specific NPS park or NPS geographic region. These peer-reviewed publications help to shape interpretation, historical research, educational programming, preservation, and consideration of future NPS sites. While accessible to the public, these studies are often seamless incorporated within the NPS system. Though I had been a frequent park attendee and an occasional lecturer at special events, I had never worked with NPS on a study. My conversations, however, convinced me to say yes. I am glad that I did.

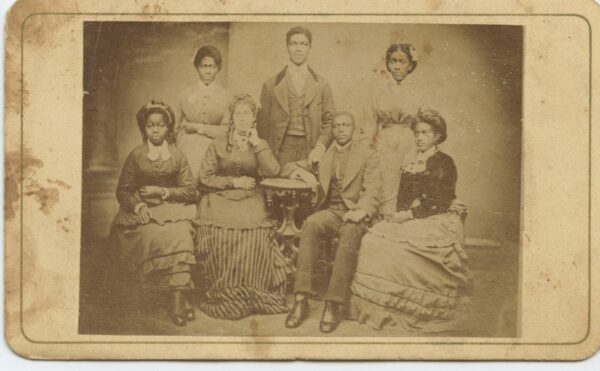

E. F. Hovey, Carolina Singers (Fairfield Normal Institute), 1873. Courtesy Hilary N. Green

With Keith S. Hébert (Auburn Univ.), I researched and developed a regional study exploring the emergence of African Americans schools throughout the South and helped to contextual this Reconstruction-era phenomena for future programming and interpretation. Developing ideas from my first monograph and covering the long Reconstruction chronology, the study encompassed the Civil War era to the 1890s, specifically the developments that came after the Blair Bill of 1890, including the Second Morrill Act and creation of Jim Crow schooling provisions. We focused not only on the former Confederate states but included several border states, as the sponsoring NPS regional unit included Delaware, Maryland, and Washington, DC.

Starting in 2019, the archival research process was much like other projects. I used traditional physical archival repositories and digital archival collections. COVID-19 added some complications, but I maximized digital collections and the generosity of archivists and librarians in the research process. For all historic resource studies, NPS requires the author to provide copies of the primary sources for future use, so I had to carefully compile digital versions of all the sources I found.

With the research done, the writing process proceeded in stages. NPS required me to submit outlines for the historical overview, a detailed bibliography, and proposed tables and charts. After receiving approval on these components, I drafted the historical overview and addressed all feedback received in the thorough review process. As I worked on this component, my collaborator assessed the cultural resources and assets across the NPS region, which offered specific examples to highlight in possible exhibitions or wayside markers. In other cases, my collaborator used this section to identify possible new additions of sites with physical, cultural, and historical significance to understanding African American education within the NPS system. Together, we assembled the final study and presented our findings to NPS personnel before the official publication. Published in August 2022, the final study is available for free.

I proudly became part of a cadre of scholars who have translated our scholarship for wider publics and made lasting contributions to the shared understandings of the American past.

The process was incredibly rewarding. It introduced me to a host of NPS employees, who are dedicated professionals committed to the stewardship, interpretation, and programming at the various NPS sites. It also introduced me to a community of scholars who themselves had crafted resource studies on an array of topics. I proudly became part of a cadre of scholars who have translated our scholarship for wider publics and made lasting contributions to the shared understandings of the American past.

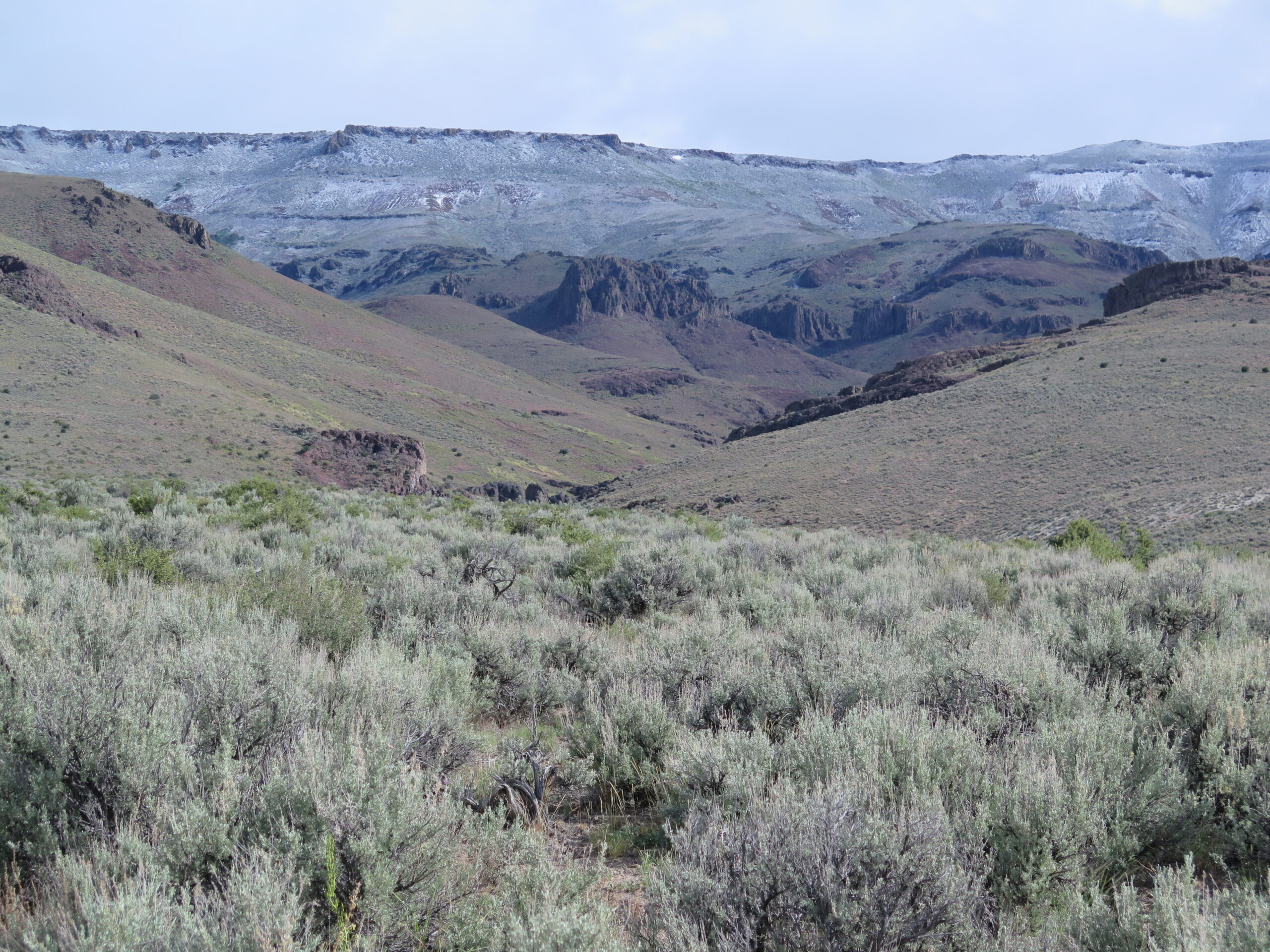

These benefits encouraged me to consider developing a new research project as a historic resource study. My new research focuses on the African American experience in Alaska during the long Reconstruction era. A historic study would fill a gap in the current framing of the historical era and enhance the existing NPS Reconstruction Era Historic Network. African Americans defined the promise of Reconstruction in the South and American West but also in Alaska territories, which the United States acquired from Russia in 1867. Before trains, airplanes, and highways, African Americans, many of whom were formerly enslaved, whalers, Civil War veterans, and soldiers in the US army, defined notions of freedom, citizenship, and the postwar economic opportunities in Alaska while coping with new landscapes marked by extreme weather conditions, unique flora and fauna, and communication dislocation from families and communities who remained in the lower United States. As early settlers, these men and women chased Reconstruction’s promise of equality, landownership, socioeconomic possibilities, and full inclusion in the United States.

Yet the current political environment has given me pause. With the various executive orders targeting interpretations of American history and authorized reviews of exhibition content, collections, and even NPS sites’ bookstores, a historic resource study on this topic would be folly. I am deeply concerned about the careers and well-being of the NPS individual personnel and units who would commission such a study. As a result, I accept that the current moment is not conducive to another such collaboration.

African American residents persisted and built meaningful lives from Skagway to north of the Arctic Circle.

I, however, will continue with the Alaska project, as my annual research trips have revealed the necessity of this work. When the continental United States saw the systematic overthrow of Reconstruction, African Americans continued to find the fulfillment of Reconstruction’s promise—economically, socially, and politically—in the Alaska territory. The experiences of Civil War veterans Isaiah King and John Conna, Ninth Cavalry veteran and gold prospector Roshier Creecy, and businesswomen Ella J. De Saccrist and Mattie “Tootsie” Crosby deserve to be known by visitors to Alaska’s NPS sites. Before the development of the Alcan highway during World War II and statehood in 1959, these diverse African American residents persisted and built meaningful lives from Skagway to north of the Arctic Circle.

I remain open to writing a future NPS historic study based on the Alaska project. It is my intention to ensure access to all publications and research materials to the Alaska NPS regional sites as well as others in the lower 48 states. I am also committed to developing suitable programming, exhibitions, and accessible scholarship among the various museums, universities, and archival repositories in Alaska. In the meantime, I will continue to advocate for and support the NPS system to the best of my ability.

Hilary N. Green is the James B. Duke Professor of Africana Studies at Davidson College.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.