I am a recovering academic. Nearly 19 years into my second career as a consulting historian—more than double the time I spent as an assistant professor—I still struggle with the structure of an 8-to-5 job, where I spend the day at an office and track my project work in 15-minute increments. Oddly, the structures of consulting work that were so hard for me to adjust to—regular hours, working in an office, and tracking my time—helped me to survive the transition to working from home when the pandemic began. Unlike my former academic self, who took full advantage of the freedom to work whenever and wherever I wanted to, I treat my pandemic workday much like a day at the office. The skills I had to develop as a new consultant, such as focusing my attention during normal business hours and containing my work to those hours, brought me a work-life balance that has served me well during the past year.

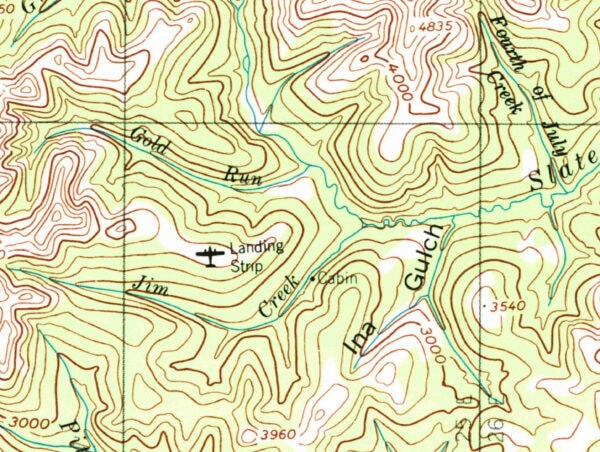

HRA staff used USGS topographical maps like this one to investigate when airfields were constructed in a remote part of Alaska. U.S. Geological Survey, public domain

My company, Historical Research Associates, Inc. (HRA), is one of the oldest history and cultural resources management consulting firms in the United States. Our 17 historians, 25 archaeologists, 6 architectural historians, and 10 administrative and support specialists assist public and private clients with historical research and writing, interpretive planning, exhibition development, and compliance with historic preservation and cultural resource laws. At any given moment, our active projects might include providing research and expert witness testimony for water rights or Superfund litigation, writing the administrative history of a National Park Service (NPS) unit, developing an interpretive plan for a historic site, conducting cultural resource surveys in advance of wind farm or pipeline construction, or evaluating buildings for National Register eligibility.

During the pandemic, in addition to the same dislocations that everyone experienced, HRA historians have faced a new challenge: how to sustain project work while archives and other repositories are closed. We cannot fall back onto secondary or side projects, as some advice suggests, because our clients have specific deadlines driven by things like court calendars and construction schedules. Nearly all our projects involve in-person research in repositories such as branches of the National Archives, the Library of Congress, state and local historical societies, university archives and special collections, local libraries, and government offices. We travel across the country to do this work, with most of us spending one week per month on the road. Since COVID arrived in the United States last year, we have been unable to conduct in-person research due to repository closures and a company decision to avoid airplane travel. That was a difficult choice, because it meant having to put some projects on hold. But we had to consider the health risks to our staff and the harm to our safety rating if someone contracted COVID on the job.

The skills I had to develop as a new consultant brought me a work-life balance that has served me well during the past year.

Like historians in academic settings, we have been forced to develop a variety of research workarounds for pandemic conditions, one of which is keeping our projects moving forward by using digitized records available online. HRA historians already had a lot of experience using online collections, but we never had to rely upon them exclusively, as we have now had to do for more than a year. Tools we have used extensively this year include the Bureau of Land Management’s General Land Office records, HathiTrust, Commissioner of Indian Affairs annual reports, and the Library of Congress’s Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps. We also have benefited from the many state and local historical societies with extensive online collections of photographs, newspapers, and other frequently used materials.

The pandemic also prompted us to dig deeper into these resources, as well as to find new ones. For example, I discovered through some searches in Montana Newspapers that the local paper in Madison County carried minutes from county commissioners’ meetings during the 1910s. I then used word searches to help answer a client’s questions about county road construction. In another project, I used digitized topographical maps to investigate when airfields were constructed in a remote part of Alaska. And I found old septic tank permits online for one state, which—believe it or not—was pretty exciting. Being forced to spend more time combing the internet has brought to light new tools and resources that we will continue to use even after archives reopen.

Archives and university libraries have a growing number of staff returning on-site these days, and researchers may be able to get remote assistance with small tasks. A reference librarian at the University of Washington, who responded to my inquiry about whether a microfiche set was available through interlibrary loan, found and scanned two documents I needed. An archivist at Harpers Ferry Center provided us with finding aids and scanned records that we needed to complete a project for the NPS. Such support is invaluable—I hope to thank these dedicated professionals in person someday.

Archivists’ support is invaluable—I hope to thank these dedicated professionals in person someday.

HRA has continued to bid on new projects throughout the pandemic, despite our limited ability to conduct archival research. We have responded to public requests for proposals for projects such as administrative histories or interpretive plans for the NPS, and we have developed scopes of work and budgets for attorneys seeking historical expertise for litigation. Throughout the process, we have communicated clearly with prospective clients about what we can and cannot accomplish while archives are closed. Usually, this results in a two-phase scope of work: Phase 1 is what can be done under current conditions, while Phase 2 is what we can do when repositories reopen. This isn’t dramatically different from how we scoped projects in the past, but the new challenge is that clients may need information well before we can get back into archives. Online collections do not always provide enough detail to find definitive answers, but they are a good start. For example, we can help attorneys evaluate the viability of their legal arguments, even if we cannot yet obtain all of the historical records needed for trial.

As vaccinations roll out and archives reopen, we look forward to a summer spent returning to travel and research. The digital collections we relied on for the last 15 months have been essential to continuing our work. However, they simply are not enough to provide all the information our clients need. Yet, being forced to work from home has opened our eyes to many new online resources, and we have learned how to use existing tools in new combinations, which will enhance our work going forward.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.