Editor’s Note: This is the first installment in a two-part column. The second installment can be found here.

“A mural should be as powerful and moving as a symphony,” the 25-year-old artist Myer Shaffer wrote in the Los Angeles Jewish Community Press in 1937, “not a pretty melody in paint.”

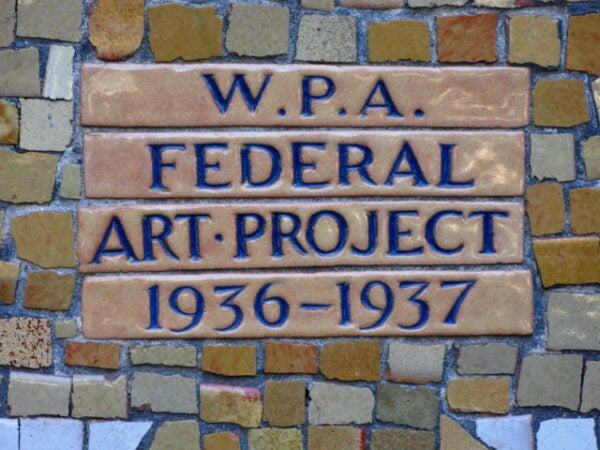

Investigating destroyed artworks can open up new understandings of the New Deal. Rootytootoot/Flickr/CC BY-NC 2.0

Shaffer, a student of the Mexican social realist painter David Alfaro Siqueiros, had recently completed two murals funded by the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project (WPA-FAP), the New Deal program responsible for much of the public artwork found across the United States to this day. The Social Aspects of Tuberculosis (1936) was located at the Los Angeles Tubercular Sanatorium (today’s City of Hope cancer center) and The Elder in Relation to Society (1937) at the since-demolished Mount Sinai Home for Chronic Invalids.

By 1938, both murals had been destroyed.

I came across the story of Shaffer’s short-lived murals while working as a research assistant with the Living New Deal, a crowdsourced public history project based at the University of California, Berkeley. Since 2012, the project has been documenting the legacy of the New Deal across the country. Our online map—a collaboration between the project’s expert team of geographers and historians as well as observant members of the public—vividly illustrates just how extensively this period of federal investment in public works continues to shape the national landscape.

My research is based in Los Angeles, a city transformed by the New Deal. As I delve into stacks of yellowing high school yearbooks, scour sidewalks for contractors’ stamps, and heft weighty volumes of the Los Angeles School Journal through the stacks of the University of California, Los Angeles’s research library, I have begun to think of Shaffer’s murals—which so briefly graced the walls of two institutions central to the city’s care economy—as an apt metaphor for the New Deal writ large. This was a moment when artists, administrators, and ordinary Americans began thinking about the social contract in new ways. Eighty years later, can public history help us recover not only the memory of Shaffer’s groundbreaking murals, but some remnants of the radical hope manifested therein?

I have begun to think of Shaffer’s murals as an apt metaphor for the New Deal writ large.

We can locate these remnants in the lasting (but often unmarked) public works I am charged with mapping for the Living New Deal, as well as social aid projects that have fallen through the cracks of collective memory. There was the Public Works Administration (PWA), which allocated $9,380,000 to the Los Angeles Unified School District to rehabilitate 130 schools—many still in operation today—that were damaged in the severe 1933 Long Beach earthquake. Some projects were more obscure, like the State Relief Administration’s Commodity Distribution Division, which supplied fresh vegetables through community garden projects, and the Visiting Housekeepers Project, which provided “home assistance and childcare in relief cases wherein the homemaker is totally or partially disabled because of illness or other cause.”

Sometimes we must peel back the layers of literal and figurative whitewash to locate these remnants of radical hope. While many surviving New Deal murals perpetuate a mythic narrative of US history, Shaffer’s depicted uncomfortable contemporary truths that raised questions about the social contract, public welfare, and the nature of community. Historian Sarah Schrank describes how before painting The Social Aspects of Tuberculosis, Shaffer conducted extensive interviews with patients at the sanatorium, eager to complicate Los Angeles boosters’ utopian narratives by portraying the disease as a symptom of socioeconomic disparity. His mural at the Mount Sinai Home for Chronic Invalids issued “a plea for united understanding and a closer brotherhood” (according to the Jewish Community Press) by depicting five figures of different ethnicities alongside a personification of the great equalizer: death.

These truths and the questions they raised were painted over promptly with whitewash by the hospitals’ respective administrations, likely with the approbation and even encouragement of southern California’s FAP supervisor Stanton Macdonald-Wright, a fierce critic of social realism. (“You couldn’t exactly weed them out,” Macdonald-Wright said of social realist artists in a 1964 oral history, “you had to get rid of them by stealth more than any other way.”) The layers of whitewash erased one young muralist’s audacity to reimagine the national future along more visionary, complex, and perhaps even hopeful lines.

In response to the whitewashing of his murals, Shaffer began logging other public artworks destroyed by local authorities in the pages of the Jewish Community Press. These included Charles Kassler’s Pastoral California (1934) at Fullerton Union High School, which was funded by the Public Works of Art Project, an FAP predecessor. Kassler’s mural, historian Caroline Luce has argued, “emphasized the disparities of wealth and power in the colonial period” and “presented students at the school a history lesson about inequality and racism.” This “history lesson” about American empire and migration was deemed inappropriate by the school’s Board of Directors, who painted over Pastoral California in 1939. It was restored in 1997 and, in 2021, granted local landmark status by a unanimous vote of the Fullerton City Council.

Historical narratives have gained complexity in the name of inspiring contemporary change.

There is undeniable power in remembering the moment of radical hope that the New Deal represented by recovering its remnants. They are surprisingly tenacious. In the age of COVID-19, we witnessed the implementation of mutual aid networks that might be considered grassroots analogs to the Commodity Distribution Division or the Visiting Housekeepers Project. We have seen public art breathe new life into communities. Historical narratives have gained complexity in the name of inspiring contemporary change. Much work remains. But, like a grainy recording of a “powerful and moving symphony” performed but a handful of times nearly a century ago, the memory of Shaffer’s murals remind me that out of crisis can be born the impetus to envision a better future.

Might New Deal artwork, even today, provoke the reimagining of democratic life?

Natalie D. McDonald is an MA student at California State University, Northridge.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.