I often straddle divides, which can become rather uncomfortable at times—forever betwixt and between. At one point I was an Upper Skagit who wore the green and gray uniform of a National Park Service ranger. My felt ranger hat hangs on the wall in my university faculty office to this day as a reminder of that period in my life. It reminds me that I have changed over time, history has changed over time, and the National Park Service has changed too.

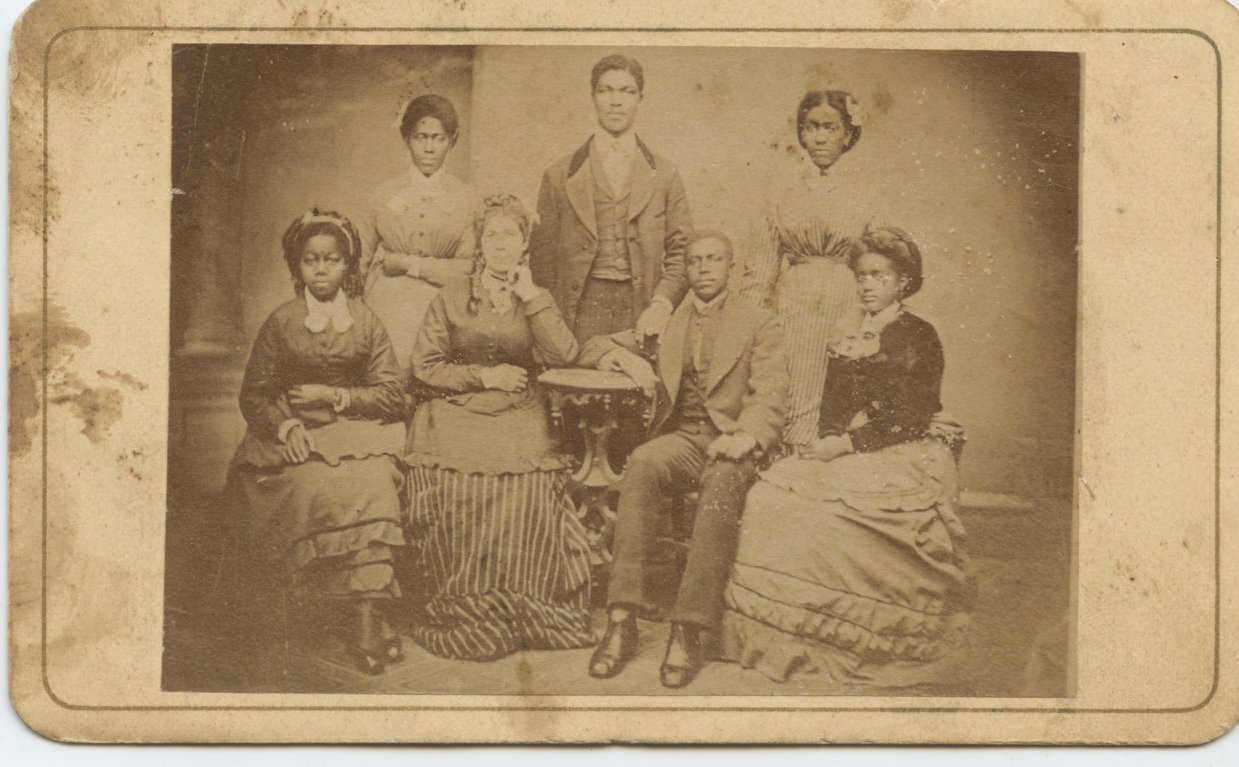

For his graduation, Ryan W. Booth wore a mortarboard cap made by his mother out of cedar bark, following traditions evidenced on the land of North Cascades National Park. Ryan W. Booth

America’s best idea, as Wallace Stegner coined it, contained other hidden and sometimes sinister implications. Many of the “crown jewel” national parks predate the 1916 creation of the National Park Service (NPS). In 1910, half of the Blackfeet Reservation was lopped off to help create Glacier National Park, as historian Mark David Spence documented in Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks (2000). While the land may have been Indigenous, the title was held by the federal government, which was loath to let Native people live on it. The Blackfeet were so close to Glacier and so far from God in the view of the US government.

After the creation of the NPS, a concerted campaign began to erase Native people from the history of the parks. The government had their reasons for this. Mostly the NPS saw Native people and their claims to the national parks as nuisances or as spoiling the Anglo-American views of “pristine” wilderness. I use pristine in a tongue-in-cheek manner, since at that time the government also hired landscape architects to shape the parks and scores of hunters to cull herds of bison and elk and annihilate predator species such as wolves. Of course, early park boosters also built grand lodges, railroad terminals, and roadways, but these were for the “right sort” of visitors—namely wealthy, influential, and largely urbane Americans. Native American residents spoiled the view.

This attempted erasure appears in the attitudes of authors such as Marie Augspurger. Her book Yellowstone National Park (1948) peddled the myths that “the Indians called it ‘Burning Mountain’ and fearless warriors and hunters shunned it with superstition and horror.” This quote came from the very first page of the book! According to such writers, Indians were too afraid of nature to even venture into Yellowstone, and yet some managed to be “fearless.” It is a conundrum for all ages. Indians were both fearless warriors when historians needed them to be and cowardly cretins when that served their purposes best.

The old line “Indians were here once but have moved on” was on its own journey into oblivion.

When I began working as an intern and later as a National Park Service ranger in the 1990s, the remnants of this history found in old museum exhibits and other interpretive materials was beginning to disappear. The old line “Indians were here once but have moved on” was on its own journey into oblivion. With the impetus for government-to-government consultation between tribes and the NPS, the agency shifted the official perspective as they listened to the tribes.

The evidence of Native ownership was on the land. As researchers delved more and more into archaeology, geology, and other evidence, their findings overwhelmed park staff. Native occupation of these lands that became national parks was incontrovertible. At North Cascades National Park, where I worked, the park archaeologist found caches of supplies hidden centuries ago in very difficult and harsh alpine areas. While some were surprised by these finds, I thought, If people today are climbing mountains, why couldn’t Native people too? Despite prohibitions against gathering traditional plants and materials on NPS lands, Native people exercised their treaty rights. I saw this on western red cedars at North Cascades, for instance, where cedar bark had been stripped both in the present day but also in the distant past.

While the history presented at the parks has changed, so too has NPS culture. In early NPS lore, the first two directors emerged as lionized figures. Stephen T. Mather and Horace Albright felt like gods who ruled from on high, whose dictates were followed and copied by park superintendents for decades thereafter. But by the end of the 20th century, government-to-government consultation became the norm—which mostly entailed letting tribal governments know what was happening in our national parks, as required by law.

In the 21st century, this has morphed into actually including Native people in park planning from the very beginning instead of waiting to inform them at the end of the process. With the appointment of Deb Haaland (Pueblo of Laguna) as Secretary of the Interior and Chuck Sams (Cayuse and Walla Walla) as NPS director in 2021, the first Native Americans to hold these positions, the transformation of the NPS was readily apparent. Native people were not erased nor were they on the periphery—they were at the heart of the National Park Service.

If people today are climbing mountains, why couldn’t Native people too?

As historians, we look for change over time. In the nearly 30 years since I first worked for the agency, I changed from a teenage intern to full-time ranger to tenure-track professor. Change also comes on the organizational and national levels. If an organization as hidebound to tradition and mission like the National Park Service can change its views of Native Americans, there is hope for the benefit of all future generations to enjoy these special places.

Ryan W. Booth (Upper Skagit Tribe) is assistant professor of history at Washington State University. He was a park ranger for the National Park Service for five years.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.