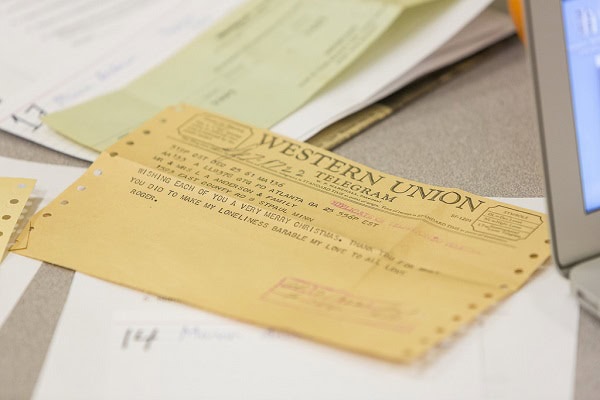

Marvin Anderson sent this telegram to his parents while he was at a student at Morehouse, explaining that he couldn’t come home for Christmas. Photo courtesy of Macalester College

In the late 1950s, the Department of Transportation started construction on I-94, linking the downtowns of Minneapolis and St. Paul. Planners had two options: a northern route along abandoned railroad tracks or a central route through Rondo, a majority black neighborhood in St. Paul. They chose the latter, splitting the community and bulldozing its business district. Some Rondo residents battled the construction in the courts; others were forcibly removed by police; still others accepted lowball offers for their homes and moved away. The process changed Rondo forever. Yet for decades, community members implored the city: “Remember Rondo!” In July 2015, St. Paul’s mayor finally delivered an apology. “Today we acknowledge the sins of our past,” he said at a healing ceremony. “We regret the stain of racism that allowed so callous a decision as the one that led to families being dragged from their homes, creating a diaspora of the African American community in the City of St. Paul.”

The apology and long-standing efforts by the neighborhood to preserve its identity made a new partnership between Macalester College and Rondo Avenue, Inc. (RAI) apropos. We decided to team-teach a History Harvest course to learn more about Rondo. Macalester’s close proximity to the neighborhood made collaboration more accessible to our students. The History Harvest model aligned with RAI’s goal of preserving the history of Rondo and with Macalester’s emphasis on community-engaged curriculum.

In a History Harvest, members of a community bring personal artifacts to one location on a certain day to be photographed, digitized, and documented. An online digital archive results, and participants leave with their heirloom in hand. (One “Remembering Rondo” participant brought in her grandmother’s 100-year-old soup tureen that she will pass down to her children.) The final digital project democratizes “the archive” and perhaps even history itself. Since communities generate their own virtual archives with assistance from students, a History Harvest acknowledges that archives, libraries, and museums highlight some histories and suppress others. The model empowers students to organize the event and develop the collection, and centers community members as attendees, recipients, and collaborators.

Remembering Rondo: A History Harvest combined three components: the history of African Americans in Minnesota, digital and oral history theory and methodology, and digital skills training. We hope that this chronicle of our steps, missteps, and innovations will help others run History Harvests of their own, particularly with marginalized communities.

Proposal: Seven months before our event, we met with Mr. Marvin Anderson, a beloved son of Rondo and an RAI co-founder. His enthusiasm encouraged us. He arranged for us to present our idea at an RAI board meeting. We also invited Paul Schadewald, director of Macalester’s Civic Engagement Center (CEC), who specializes in community collaborations. One of the pillars of a Macalester education is community engagement, and the CEC facilitates and maintains relations with local partners for courses across the curriculum. We explained our course plan and outcomes for RAI and received unanimous board approval.

Community Liaison: RAI hired a liaison to help students pitch the harvest to the community. Lauren Williams, a granddaughter of Rondo, helped students arrange visits to local businesses, church groups, and retirement communities. Not all harvests require a liaison, but in our case the community members’ anger, grief, and trauma lay close to the surface. Anticipating reticence toward outsiders “harvesting” their history, RAI’s decision to hire a liaison augmented our success.

“Rondo First”: We created a “Rondo First” policy, embodied in many details of the project. For example, save-the-date postcards, which our students passed out at local events and to businesses and church groups, featured the RAI logo but not Macalester’s. The archive was set up to direct web traffic to RAI instead of Macalester. These decisions showed our commitment to prioritizing RAI’s website and its local history project.

Transportation: Rondo remains a geographically tight-knit community. Many still live near I-94, so it made sense to select the community center in the heart of Old Rondo. Since Minnesota winters can extend into March, we thought participation might increase if we offered a shuttle service for the community’s elders. We were wrong. In fact, some community members found this demeaning. We underestimated the mobility of these elders and won’t make that mistake again.

Make It a Party: In keeping with the “Rondo First” policy, our students thought carefully about logistics. They decided that if they planned a fun event, they would have good turnout. To avoid an assembly-line feel (check in, sign forms, get interviewed, digitize objects, good-bye), the students arranged the harvest stations along the walls. These included a welcome desk, an area for signing consent forms, interview tables for participants to share their stories about the artifacts, and a digitization station, with cameras and scanners. The setup reduced ambient noise in the artifact interviews.

Long tables in the center of the room provided a welcoming space for lunch. We ordered food from a neighborhood BBQ joint, thereby funneling nearly $1,000 back into the community. Lunch was perhaps the most significant aspect of the day. The harvest became secondary to cross-cultural, intergenerational conversations, allowing the students to build trust with community members. It also happened to be Mr. Anderson’s birthday, so we ordered cake and had a real party.

Oral History: For residents willing to share longer stories, we rented a room specifically for oral history. We enlisted four student volunteers from courses in documentary studies and photography. The professor and volunteers brought professional equipment, shot supplemental footage, and made a short documentary afterward. Our students later crowdsourced the transcriptions in 15-minute segments using Google Docs. Adding a longer oral history component created some minor challenges, so unless you have two instructors and other technical support, we do not recommend attempting the harvest and oral history on the same day.

Post-Harvest: After the harvest, the course shifted from event planning to archival production. The students spent three weeks on a shared metadata Google spreadsheet before they even received access to Omeka (an open source archival management system developed by the Roy Rosenzweig Center at George Mason University). Devoting time to the metadata meant that students were prepared to upload the artifacts to the archive, which they accomplished together in less than an hour. During this phase they learned marketable skills that expanded their résumés.

In retrospect, we made a couple of errors at this point. First, students struggled with the abrupt transition from community engagement to archiving. We could have continued incorporating community visits. Second, we attempted too much, including writing a Wikipedia entry as a class. This was to the detriment of the archive, and we professors spent hours post-semester providing artifact transcriptions complying with Americans with Disabilities Act standards. Students would have been better served by doing these transcriptions themselves; they would have learned more, felt connected to Rondo’s history, and been able to transfer their knowledge to exhibit creation.

Budget: We overspent. Our harvest ended up costing nearly $4,000, but the return—the partnership with RAI and the student experience—was incalculable. If you have the equipment, an appropriate venue, and can forgo transportation, you can run the event for virtually nothing. That said, we highly recommend hosting lunch.

Maintenance: After the harvest, we scanned the release forms and kept them with the items in Omeka (set to private). These will live in our history department until RAI installs its own instance of Omeka. Then we will download our database and hand everything over. Community members want even the virtual artifacts to reside in Rondo. We wholeheartedly agree.

As with many marginalized communities, building trust between residents and institutions requires a long-term commitment. After our event, we received e-mails and phone calls from residents who hesitated to come or were unable to attend. As Mr. Anderson put it, “They were waiting to see if it would be fun.” Well, it was fun, and we are thrilled to be hosting another Rondo Harvest in 2017. Moving forward, we hope to integrate the archive into local K–12 curricula and offer training to interested teachers.

Mr. Anderson loves the archive (as does RAI), but he’s more enamored with what the students learned. Prior to the event, our students were so concerned about their relative privilege as middle-class college students that they felt nearly immobilized, but an hour into the event, their reservations vanished, due in large part to the community’s kindness and compassion. In the wake of alarming realities like the nearby murder of Philando Castile by a police officer in July 2016, Rondo’s history is also the history of our present. When Black Lives Matter protesters shut down the highway, they stood on I-94, which still cuts through Rondo. That symbolism is hard to ignore, and thankfully it is one that is no longer lost on our students.

Rebecca S. Wingo is the Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Digital Liberal Arts at Macalester College. She specializes in the history of the indigenous and American West, in addition to digital and public history. Amy C. Sullivan is an independent scholar in Minneapolis and occasional visiting assistant professor at Macalester, teaching courses on the history of medicine, childhood, and feminism.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.