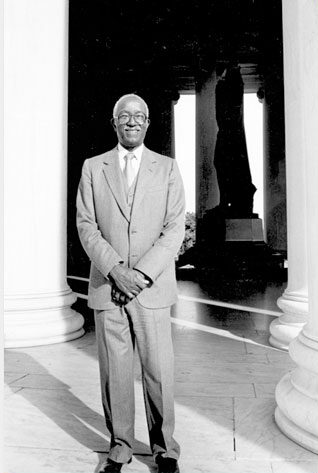

John Hope Franklin

When I came to the University of California at Berkeley as an undergraduate, the textbook I used in the American history survey course was no more enlightened than the textbook I had read in high school or the textbook used in most Ivy League colleges, in which two distinguished historians from Harvard and Columbia said of slavery, “Sambo suffered less than any other class in the South. Although brought here by force, the incurably optimistic negro soon became attached to the country and devoted to his ‘white folks.’” When I completed my PhD at Berkeley in 1958, having written a dissertation on free blacks in the antebellum North, a distinguished senior historian advised me to get back into the mainstream of American history. What some called “Negro history” had no standing in academic or nonacademic America. The U. S. history we learned and read was the history of Anglo-Saxons and northern Europeans. That was the kind of history historians wrote.

John Hope Franklin made an enormous difference in how we view and teach our past—how we think about African American history, the history of the South, and the history of the United States. Like Carter G. Woodson and W.E.B. Du Bois, Franklin demonstrated to a skeptical or indifferent profession that the history of black Americans was a legitimate field for scholarly inquiry and investigation. Franklin’s magisterial work, From Slavery to Freedom, introduced more than 3 million students and nonstudents alike to African American history, to the idea that African Americans had a history—a past based not only on what white men did to black Americans but on what black Americans did for themselves. When African American history was incorporated into American history, it did more than enter the mainstream, it redefined the mainstream.

Like our finest and most disturbing historians, John Hope Franklin was never “fashionable.” He demonstrated both independence of mind and a deep respect for the complexity and integrity of the past. He was too good a historian to romanticize the past, to replace old lies with new myths or with eulogistic sketches of heroes and heroines. He was too good a historian to subordinate history to ideology, to the polemical needs of the present. He fully appreciated the ways in which race hustlers and ethnocentrists, white and black, have sought to use the past, and how for more than a century the abuse of the past by historians and others had helped to legitimize a complex of racial laws, practices, and beliefs.

We met 53 years ago, when he came to Berkeley in the summer of 1956 to teach a course in American social history. I served as his graduate assistant. Our friendship flourished over discussions of my dissertation; a more inclusive American history; the workings of Jim Crow, South and North; and the future of black studies and race relations. The next year the Franklin family moved to New York, where John Hope had been named the first African American to head a history department at a traditionally white college (Brooklyn). The story made the front page of the New York Times but no real estate dealer in Brooklyn would even show them a house.

Whatever we discussed that summer, we never imagined that some years later I would introduce him to a symposium on the law and civil rights at the University of Mississippi or that we would engage in a public conversation at the University of South Carolina and at a conference on Jim Crow at North Carolina Central University. Nor had we anticipated dining together in his presidential suite at the Peabody Hotel in Nashville—the same hotel that in 1964 hosted the annual meeting of the Southern Historical Association and would then have barred blacks from sleeping or dining there. In a highly anticipated event, in 1994, it was my privilege to present Franklin the Bruce Catton prize for lifetime achievement in the writing of history on behalf of the Society of American Historians.

Although separated by a continent, we continued to see each other during these years of civil and not so civil strife. Irreverent and increasingly radical, John Hope refused to conform to other people’s expectations of him. And he refused, as he said, “to paper over or mislead the world” on the state of race relations. Since childhood he had faced humiliations, and these he never forgot or forgave. “A day, and often an hour didn’t go by, without my feeling the color of my skin. As has been true all of my life, being ambitious and black guaranteed that I would stand out.”

The erosion of race relations in the Reagan-Bush era left America deeply divided, separate and unequal, and Franklin intensely troubled. By the turn of the century, Franklin was convinced both that blacks had come to be as entrapped by their poverty as they had been by Jim Crow, and that Americans should be held accountable for centuries of enslaved labor. “My views regarding reparations,” Franklin declared in a note he sent me recently, “are that this country owes African Americans an enormous debt not only for the years of uncompensated service during slavery that helped develop the country and build private fortunes, but also for the immense contributions in building the nation’s infrastructure, ranging from road building to the erection of public buildings of every conceivable kind. I am realist enough to know, however, that Americans who know their history and still fight even against such tokenism as affirmative action are much too absorbed in protecting their own wealth to concede that they owe anyone anything.”

In his scholarship, in his teaching in his activism, in his personal humanism, John Hope Franklin has left his distinctive mark. Throughout a very full life, he used the pen and his voice to “force America to keep faith with herself,” to compel this nation to face up to its contradictions. The way to remember him is to act on the commitments he made, the concerns he voiced, and the vision he embraced.

John Hope Franklin, 1915–2009

Born, Rentiesville, Oklahoma, January 2, 1915, to Mollie Parker and Buck Colbert Franklin. BA, 1935, Fisk University; MA, 1936, PhD, 1941, Harvard University. Taught at numerous schools including Fisk, St. Augustines, North Carolina Central University,* Howard University, Brooklyn College, University of Chicago, and Duke University, from where he retired as the James B. Duke Emeritus Professor of History.

Publications include From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans, The Militant South, 1800–1861, Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation (with Loren Schweninger), Mirror to America: The Autobiography of John Hope Franklin.

Adviser to NAACP on Brown v. Board of Education. President, Organization of American Historians, 1974–75; American Historical Association, 1979. Received Presidential Medal of Freedom, 1995; chair of “One America in the 21st Century: The President’s Initiative on Race,” 1997. John W. Kluge Prize for lifetime achievement in the study of humanity, 2006.

Died, March 25, 2009, of congestive heart failure at the Duke University Hospital in Durham, North Carolina.

Leon Litwack is the Alexander F. and May T. Morrison Professor of American History Emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley.