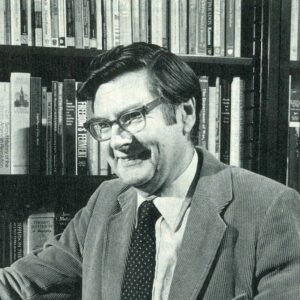

Reginald Horsman, distinguished professor of history at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee and eminent scholar, died on August 20, 2025.

Reg was born in Leeds, Yorkshire, England, in 1931. His family moved to Leicester, where Reg had his early education before attending the University of Birmingham, where he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in American history in 1952 and 1955. Reg then attended Indiana University, earning a PhD in 1958. There, he met Lenore McNabb and they married in 1955. The couple shared a passion for classical music, opera especially. They moved to Milwaukee in 1958 when Reg began his long tenure at UW-Milwaukee. Lenore pursued her singing career, and her talents gained wide recognition as she enjoyed tours in Europe and the United States. She died in 2023. The couple are survived by three children—Janine, Mara, and John—and six grandchildren.

Reg also leaves an outstanding legacy in his academic career. His scholarship included 13 books and many essays for academic journals, book reviews, and paper presentations at conferences. For years, he taught the department’s two introductory survey classes in American history, each enrolling hundreds of students, and he won multiple university teaching awards. His colleagues always valued Reg for his loyalty and service to the department, including as department chair from 1970 to 1972. Reg was named UWM Distinguished Professor in 1973. He retired in 1999 after 41 years at the university.

Reginald Horsman did not champion a particular philosophy of history or adhere to one methodology. He often said he pursued a subject just because it interested him. A brief sampling of his many books illustrates this point. His most influential work, still used in colleges today, was Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism (Harvard Univ. Press, 1981). “A work of monumental scope,” according to one reviewer, this book explored the contrasting cultures of the American founders, products of the Enlightenment, and the successive generation, products of the Romantic movement. The first ideology posited a standard human nature and inscribed universal ideals of personal freedom into its political discourse. It envisioned “an empire of liberty” as its worldly mission. Romanticism turned away from these standards. Accepting German notions of nationhood and English glorifications of the Anglo-Saxon past, Americans of the early 19th century accepted the notion of racial distinctiveness. The new direction became more invidious when science advanced new theories of polygenesis and racial differentiation. As one reviewer wrote, the book “permanently changed the accepted scholarly understanding of racial Anglo-Saxonism.”

Reg reinforced his work in scientific racism with the biography Josiah Nott of Mobile: Southerner, Physician, and Racial Theorist (Louisiana State Univ. Press, 1987). Nott (1804–73) had important achievements in medicine while turning his scientific ideas to the defense of white racial supremacy. Reg’s next book, Frontier Doctor: William Beaumont, America’s First Great Medical Scientist (Univ. of Missouri Press, 1996), was about a man with no formal education; “he carried out his bold experiments knowing nothing of the theoretical debates raging in London and Paris.”

Reg had an active retirement, producing one more book with Feast or Famine: Food and Drink in American Westward Expansion (Univ. of Missouri Press, 2008). In this study, called “a gastronomic narration of nineteenth-century westering,” Reg entered the domain of material culture, quite removed from the rarified theoretical outposts of Race and Manifest Destiny. Here we see the westering adventure up close—among trappers and explorers, in the army forts, on stagecoach, steamboat, and railroad. This book offered “a wealth of information from a seemingly limitless number of sources.”

Such was the versatility of historian Reginald Horsman. His diverse scholarship is matched only by his value as a colleague. He had sound, rational judgments for us in the challenges we faced; he knew all the occult rivulets of the university system and pointed the way for our successful negotiations with them. Reg participated enthusiastically in the extracurricular life of the history department—attending social gatherings, dinners, picnics, and ceremonies of various kinds. We all came to know him by that robust laugh that could fill a room.

J. David Hoeveler

University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee (emeritus)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.