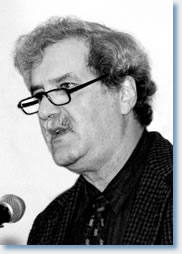

Reginald E. Zelnik

Reggie Zelnik was among the most admired and beloved members of the Russian history field. His books are classics. His wisdom and concern for colleagues and students are legendary. In 1996, he received the Nancy Lyman Roelker Mentorship Award, presented by the AHA. In the same year, the journal Russian History published a Festschrift in his honor, a tribute from colleagues and former students. On May 17, 2004, while walking on the Berkeley campus, his academic home for 40 years, he was struck by a delivery truck and died at the site. His sudden and senseless death has left a gaping hole in our hearts and in our scholarly community. He was a very special man.

Born in New York City on May 8, 1936, Zelnik received his BA from Princeton University in 1956. After active service in the U.S. Navy from 1957 to 1959 (when he began his study of Russian), he entered the graduate program at Stanford University, receiving his MA in 1961 and PhD in 1966. After teaching for a year at Indiana University, in 1964 he joined the history department at the University of California at Berkeley. At Berkeley, he chaired the Center for Slavic and East European Studies, 1977–80, and the history department, 1994–97. He was active also in the AHA, AAASS, SSRC, and NCEEER. Colleagues everywhere, in Russia as well as at home, valued his professional judgment and gentle sense of humor.

Zelnik leaves not only a legacy of love and affection, but an intellectual legacy as well. Arriving on the Berkeley campus when the Free Speech Movement was first starting up, he was drawn into the local events by the same concern for human rights and civic justice that inspired his work on Russian labor history. Troubled by the war in Vietnam, he helped produce a “citizens’ white paper,” analyzing available sources on American foreign policy with Franz Schurmann and Peter Dale Scott, The Politics of Escalation in Vietnam (1966). His first academic book, Labor and Society in Tsarist Russia: The Factory Workers of St. Petersburg, 1855–1870 (Stanford, 1971), was researched under the difficult conditions of the early U.S.–Soviet scholarly exchange. It retains the freshness and originality that distinguished it at the time. Tracing the interaction between educated and laboring classes, it reaches beyond the factory into society at large.

Zelnik’s second major publication turned from the life of the city to the psychology of its inhabitants. Translating and editing a Soviet-era worker memoir, published as A Radical Worker in Tsarist Russia: The Autobiography of Semen Kanatchikov (Stanford, 1986), Zelnik demonstrated how political loyalties were shaped by personal experience. Displaying the same ability to move from the focused incident or personality to the major interpretive issues, Law and Disorder on the Narova River: The Kreenholm Strike of 1872 (California, 1995) links particular life stories (indeed personal narratives), collective movements, and institutional structures (the operation of the law and the behavior of its defenders). It shows how individuals at the top and bottom of the social hierarchy formed meaningful identities, not always in predictable ways, and made sense of their world. While focusing on the human dimension, Zelnik at the same time always thought in conceptual and systematic terms; at the time of his death, he was working on a comparative study of strikes in France, Germany, and Russia.

In co-editing a collection of essays with Robert Cohen, The Free Speech Movement: Reflections on a Campus Rebellion (California, 2002), Zelnik showed his loyalty to the friends and political commitments of his early career. His own contribution to the volume joins a personal perspective on the events with the scholar’s meticulous concern for detail and the ability to approach deeply felt moral issues with intellectual dispassion.

Zelnik’s most recent work continues to reflect on questions of moral choice and the evolution of personal identity. His unfinished study of the life of Anna Pankratova, dean of Soviet labor history and guardian of ideological orthodoxy, explores the ambiguities of her life and career.

Despite his standing in the field, Reggie Zelnik was entirely lacking in self-importance. His c.v. on the department web site does not mention the various professional awards that acknowledged his talents and achievements. These included fellowships from the Fulbright and Guggenheim Foundations, the Ford Foundation, the NEH, the ACLS, the Stanford Center for the Advanced Study of the Behavioral Sciences, and the Harriman Institute of Columbia University.

Reggie Zelnik is survived by his wife of 48 years, Elaine Zelnik, a son, daughter, son-in-law, grandson, and brother. The many people who experienced Reggie’s warmth and compassion will miss him dearly. Deprived of his wise perspective and remembering his lightness of touch, we honor his spirit. Those wishing to contribute to the Reginald E. Zelnik Memorial Fund, please write to Chris Egan, History Department, University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720-2550.

Laura Engelstein

Yale University