Editor’s Note: Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. was one of the founders and enthusiastic supporters of the National History Center. Just before his recent death, Schlesinger gave the following essay to Wm. Roger Louis, the chair of the National History Center’s board of trustees. The essay is based on a talk Schlesinger gave to the Century Association at a luncheon given in his honor in New York on December 14, 2006 (see “An Historian Reflects on the Relevance of History” published as a bulletin of the Century Association Archives Foundation). At the time of his death, Schlesinger was working on an expanded version of the essay for the National History Center. Some of his comments on the part the NHC might play in American public life originated in conversation and correspondence with Wm. Roger Louis; in meetings in New York City on December 12, 2001, with John Brademas, Fritz Stern, and others; in another meeting on February 19, 2002 that included Richard Gilder and Eric Foner; and in other meetings on October 6, 2003; and September 24, 2005. A version of this essay also appeared in the New York Times of January 1, 2007 under the title, “Folly’s Antidote.”

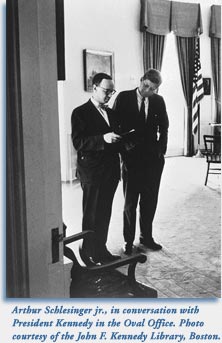

Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and JFK

I believe that there is a growing historical consciousness among the American people, and that the National History Center will help foster public understanding of national and international historical issues. It is useful to remember that history is to the nation as memory is to the individual. As persons deprived of memory become disoriented and lost, not knowing where

they have been or where they are going, so a nation denied a conception of the past will be disabled in dealing with its present and its future. “The longer you look back,” said Winston Churchill, “the further you can look forward.” Churchill believed that there was no need to justify the purpose of history. It seemed clear to him that pursuing knowledge for the sake of knowledge also meant that a study of the past helps to understand the present.

All historians are prisoners of their own experience. We bring to history the preconceptions of our personalities and the preoccupations of our age. We cannot seize on ultimate and absolute truths. So the historian is committed to a doomed enterprise—the quest for an unattainable objectivity. Yet it is an enterprise we happily pursue because of the thrill of the hunt, because exploring the past is such fun, because of the intellectual challenges involved, and because a nation needs to know its own history.

Still, conceptions of the past are far from stable. They are perennially revised by the preoccupations of the present. When new urgencies arise in our own times and lives, the historian’s spotlight shifts, probing into new areas of darkness, throwing into sharp relief things that were always there but that earlier historians had carelessly excised from the collective memory. New voices ring out of the historical dark and demand to be heard.

One has only to note how in the last half century the women’s rights movement and the civil rights movement have reformulated and renewed American history. Thus the present incessantly re-creates, reinvents, the past. In this sense, all history, as Benedetto Croce said, is contemporary history. It is these permutations of consciousness that make history so endlessly fascinating an intellectual adventure. “The one duty we owe to history,” said Oscar Wilde, “is to rewrite it.” It is thus remarkable that a distinguished literary figure seemed to anticipate the rationale for the series to be published by the Oxford University Press for the National History Center on how the interpretation of history changes over time.

We are the world’s dominant military power, and I believe history is a moral necessity for a nation possessed of such overweening might. History verifies something that President John F. Kennedy said in the first year of his thousand days: “We must face the fact that the United States is neither omnipotent nor omniscient—that we are only 6 percent of the world’s population—that we cannot impose our will upon the other 94 percent of mankind—that we cannot right every wrong or reverse each adversity—and therefore there cannot be an American solution to every world problem.”

History is the best antidote to delusions of omnipotence and omniscience. Self-knowledge is the indispensable prerequisite to self- control, for the nation as well as for the individual, and history should forever remind us of the limits of our transient perspectives. It should lead us to acknowledge our profound and chastening frailty as human beings—to recognize that the future will outwit all our certitudes, so often and so sadly displayed, and that the possibilities of the future are more various that the human intellect is designed to conceive.

Sometimes, when I am particularly de- pressed, I ascribe our behavior to stupidity—the stupidity of our leadership, the stupidity of our culture. Thirty years ago, we suffered a military defeat—fighting an unwinnable war against nationalism, the most acute of current political emotions; fighting against a country about which we knew nothing and in which we had no vital interests. Vietnam was hopeless enough, but to repeat the same arrogant folly 30 years later in Iraq is a gross instance of national stupidity. Axel Oxenstiern, the Swedish statesman, famously said, “Behold, my son, with how little wisdom the world is governed.”

A nation informed by a vivid understanding of the ironies of history is, I believe, best equipped to live with the temptations and tragedy of military power. Let us not bully our way through life, but let a growing sensitivity to history temper and civilize our use of that power. History is never a closed book or a final verdict. It is forever in the making. Let historians never sacrifice the quest for knowledge for the sake of an ideology, a religion, a race, a nation.

It is greatly to the credit of American Historical Association that it took the initiative six years ago to create the National History Center, thereby furthering the purpose of the historical profession itself and its place in American public life. The programs of the National History Center now include the investigation of a relatively new field of study, decolonization (in summer seminars for historians at the beginning of their careers); congressional briefings; a major project on the way history has been taught in American schools and universities; and, most recently, a series of public lectures about historical perspective on national and international issues co-sponsored with the Council on Foreign Relations.

The great strength of history in a free society is its capacity for self-correction. It is the endless excitement of historical writing—the search to reconstruct what went before, a quest illuminated by those ever-changing prisms that continually place old questions in a new light. The National History Center is destined, I believe, to carry forward the purpose of history for the sake of history itself and for the public debate on the relevance of history to contemporary issues.

©2006 by Arthur Schlesinger Jr., permission of The Wylie Agency.

Arthur Schlesinger Jr., who died on February 28, 2007, was a life member of the AHA renowned for his many seminal works including much-admired classic, The Age of Jackson. He received the AHA’s Award for Scholarly Distinction for 2005. As a historian who played an important role in the administration of President John F. Kennedy, Schlesinger recognized the significant public role a National History Center can play and was a keen supporter of its creation and growth.

Related Articles

Sorry, we couldn't find any articles.